Somalia famine: Historic UK visit to Mogadishu

- Published

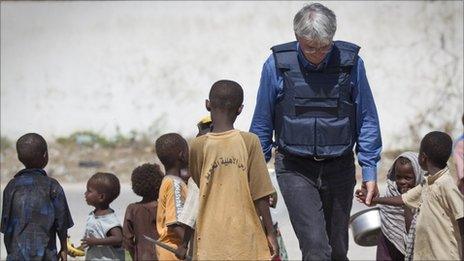

Andrew Mitchell promised more cash to tackle the immediate famine

"Hello Andrew Mitchell - welcome to Mogadishu." Less than a month ago these words would have been nothing short of fiction.

But on Wednesday a beaming Somali prime minister said just that as the UK overseas aid minister arrived in the Somali capital, two weeks after the Islamist al-Shabab pulled out of the city.

Yet the reality is that al-Qaeda-linked group still control vast swathes of the country so the premier's bodyguards were evidently twitchy, wary of suicide attacks.

In a city immortalised by the film Black Hawk Down as a bastion of lawlessness, the sight of a British minister in an armoured vehicle, body armour strapped to his chest, was nothing short of a PR coup.

An over-tired aid worker friend termed such visits "disaster porn", but it has kept Somalia on the world stage, more than five weeks after the appeal for disaster relief began.

The UK's international development secretary has promised more cash to tackle Somalia's immediate famine as well as long-term assistance, if the country new cabinet can deliver the kinds of stability that may avert a crisis in future.

His message to the Somali Prime Minister Abdiweli Mohanned Ali was: You deliver stability, and hold your ministers to account, and we'll continue to engage in the long term.

So when a convoy of armoured vehicles hurried Mr Mitchell to Villa Somalia, the seat of the Somali transitional government, with the sound of sniper fire rattling in the air, he used it as an opportunity to tell the prime minister what he hopes the British public will believe:

It is in Britain's long-term interests to see this United Nation-backed transitional government succeed - it has just 13 months left before its mandate runs out.

"More British terrorists hail from Somalia now than they do from Pakistan."

That is why Somalia matters, the minister thundered, jealously guarding Britain's protected aid budget.

Mr Mitchell appears to be a Somali optimist, though he has ruled out categorically engagement with the Islamists who still control half of the country, and have restricted access to food aid.

'Naive'

Show them the transitional government can govern well and support will follow, is his mantra - his "trickle-down" philosophy.

Some Somali watchers feel this is a little naive.

But the immediate crisis is famine. A feeding station not far from the city's main airport offered a fleeting insight into the lengths that people will go to secure food.

One woman walked six days with her children to reach Mogadishu. The prospect of violence was clearly no deterrent to the possibility of getting access to some food.

And another at the camp nearby, who clutched a baby to her breast, explained that one of her other children had perished along the road.

Death is part of the daily discourse of a people worn out by war.

The sight of makeshift tents, nestled close to one another in the shadow of bullet-scarred buildings, rams home the point that the aftershock from such acute famine is surely disease.

Farm aid

Cholera, measles and even malaria are now being reported in some of the camps - an alarming signal of what could be to come.

Finding peace in Somalia is the main challenge for donors

As more food reaches those who need it, fewer are likely to die of starvation but of illness instead.

The UK's commitment to roll out £29m ($41.5m) of more aid - (£25m to Unicef and £4m to the UN's Food and Agriculture Organisation - comes from existing development ministry funds.

It brings the total British spend to more than £50m - 80 times more than Somalia's former colonial masters, the Italians, who officials believe are not pulling their weight.

A fair chunk of the British cash will go towards preventing starvation in nearly 400,000 children and the roll out of a massive vaccination programme to try to keep measles at bay.

But as important as food will be the commitment to help farmers, in an attempt to make them more resilient to future climatic shocks.

Returning what few livestock remain back onto a healthier footing and the farming community's ability to cope will be enhanced.

But the card that trumps future famines in Somalia is a genuine return to peace - a peace which brings stability and halts massive population displacements.

Securing UK public backing for a baby dying with no food is one thing.

But winning long-term support for a country where 14 peace attempts have failed in the recent past will be one of the biggest challenges that Mr Mitchell will have to face.