Libya crisis: Profile of NTC Chair Mustafa Abdul Jalil

- Published

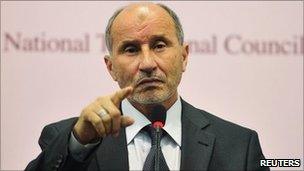

Mustafa Abdul Jalil has won the support of more than 30 foreign governments for the NTC

With the end in sight for Colonel Gaddafi's regime, the rebels' interim administration, the National Transitional Council (NTC), is poised to take power. Its chairman is Mustafa Mohammed Abdul Jalil who, until February, was Libya's justice minister. Now he looks set to lead post-Gaddafi Libya. So what is known about him?

Mr Abdul Jalil was the first member of Libya's General People's Committee, the cabinet, to quit in protest at "the excessive use of violence against unarmed protesters" by the state.

He had been sent by the government to the eastern city of Benghazi in February to deal with the beginnings of the uprising.

After witnessing the shooting and detention of peaceful demonstrators, he resigned as minister and, within days, had become the chairman of NTC.

"We are the same as people in other countries, and are looking for the same things," Mr Jalil said at the time.

"We want a democratic government, a fair constitution, and we don't want to be isolated from the world anymore."

Such a move was perhaps not unexpected from him. He has long had a reputation as someone who was prepared to defy the regime.

Rejected resignation

Mr Abdul Jalil was born in the eastern city of Bayda - the historic seat of the Sanusi dynasty and one of the first places to revolt against Col Gaddafi's rule - in 1952 and studied law and Shariah (Islamic law) at the University of Libya.

After graduating, Mr Abdul Jalil worked as a lawyer in the public prosecutor's office in Bayda before becoming a judge in 1978. In 2002, he was appointed president of the Court of Appeal. His final post before being named justice minister in 2007 was president of the court in Bayda.

During his career as a judge, he was known for ruling consistently against the government, according to the Wall Street Journal, external.

Such a reputation led to him being brought into the regime by Col Gaddafi's son, Saif al-Islam, to cast it and himself in a more reform-minded light.

As justice minister, Mr Abdul Jalil won praise from human rights groups and Western powers for his efforts to reform Libya's criminal code.

According to a leaked US diplomatic cable from January 2010, external, he was well regarded by staff at the Libyan justice ministry and several judges, who considered him fair, while US ambassador Gene Cretz described a meeting with him as "positive and encouraging".

"While Abdul Jalil has given the green light to his staff to work with us, he noted that many Libyans are still 'concerned' about the [US government's] support for Israel, and that terrorism stems from the perception that Europe and the US are 'against' Muslims," Mr Cretz wrote.

The killing of army commander Abdel Fattah Younes has exposed divisions in rebel ranks

The cable also said Human Rights Watch believed Mr Abdul Jalil's drive to change the system was driven more by his conservative point of view rather than a reformist agenda.

But in an unprecedented move in January 2010, Mr Abdul Jalil publicly defied Col Gaddafi in a televised speech to the annual General People's Congress by declaring that he intended to resign due to his "inability to overcome the difficulties facing the judicial sector".

He cited the continued detention of 300 political prisoners despite court rulings acquitting them, and the release of prisoners sentenced to death without the families of their victims being informed.

"It's as if he just wouldn't lie," Heba Morayef of Human Rights Watch told the Wall Street Journal. "I have never seen an Arab minister of justice who will publicly criticise the most powerful security agencies in the country."

But Mr Abdul Jalil's dramatic resignation was rejected by the Libyan leader. According to another US diplomatic cable, external, some observers believed that Col Gaddafi, who publicly rebuked Mr Abdul Jalil for making the remarks at the GPC, preferred to fire him on his own terms, while others said Saif al-Islam Gaddafi would not let him step down.

People in eastern Libya, however, reportedly welcomed the comments.

Tribal rivalries

Despite having a $400,000 (£250,000) bounty for his capture on his head, Mr Abdul Jalil has been busy over the last few months, seeking foreign support for the Benghazi-based NTC.

He said, back in February when the NTC was formed - with "representatives of the entire population of the Libya" - that it would manage the affairs of a post-Gaddafi Libya but would not become the government.

Once Tripoli fell, he said: "The Libyans will head for free legislative, parliamentary and presidential elections".

The NTC has now been recognised as the "legitimate interlocutor of the Libyan people" - as US National Security Adviser Tom Donilon put it - by more than 30 foreign governments, including the US and Britain.

However, the greatest challenge for Mr Abdul Jalil in the coming months may come from within his own ranks.

Earlier this month, he dismissed his entire executive committee, which functions as a cabinet, following the assassination in July of rebel commander Abdel Fattah Younes.

Some among the rebels believed he was killed by an Islamist militia allied to the NTC, while others blamed the Gaddafi regime.

However, the murder has highlighted the tribal divisions and rivalries within the rebel leadership. This could lead to inter-ethnic fighting, which is a real long-term danger for a post-Gaddafi Libya, some observers say.