Learning to live with autism in Ethiopia

- Published

Jojo is now 20 and has recently started uttering some words

The year was 1995 and Ethiopian Zemi Yunus had no idea what autism was. What she did know was that her four-year-old son, Jojo, was clearly "different from other children of his age."

Then her husband watched a television programme in the United States where they were living at the time.

It suddenly dawned on them that perhaps Jojo was autistic - certainly the symptoms described all seemed to point to this.

On the brink of returning to Ethiopia, Mrs Zemi began in earnest to research the issue.

Like many parents of autistic children, Mrs Zemi says that she had long had concerns about her son's speech, but many doctors had reassured her that boys are often "late talkers" and assuaged her fears.

But the more she found out independently, the more she recognised that her son's delayed speech, as well as his repetitive actions and his behavioural difficulties, were clearly autistic.

Unfortunately, diagnosis of the condition, particularly in the developing world, is rare. On returning to the Ethiopian capital, Addis Ababa, Mrs Zemi - who was soon running a successful business - consulted psychologists, doctors and other professionals for several years, but failed to find any answers.

Finding a school also proved difficult; many teachers dismissed Jojo as "spoilt" and he was expelled from five schools in a row. One institution even asked to be paid triple the usual fee to keep him.

Probably widespread

By this time Mrs Zemi had done extensive research, and knew that autism was probably a widespread condition in the region.

The the centre has led the Ethiopian government to begin a programme for children with special needs

In Ethiopia, though, no-one was talking about it publicly but she persevered. She began looking for other affected parents and what she found shocked her; families with autistic children mostly kept them at home, often in darkened rooms.

She even saw one little girl who was kept with her hands tied behind her back - most likely to prevent her from hitting or striking herself. This is not uncommon behaviour among children on the autistic spectrum, especially when distressed.

All this became a catalyst for Mrs Zemi to begin speaking out publicly about autism.

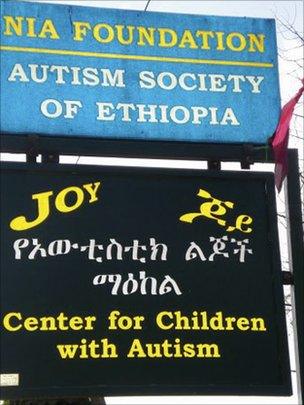

Using her successful beauty business to launch her charitable work, in 2002 she opened the Joy Centre for Children with Autism and related developmental disorders in Addis Ababa.

The school opened with just four students including her son and a staff of three employees. Today there are 75 children enrolled in the school for the autumn term and more than 30 staff members.

As it is run as a non-profit organisation, parents pay what they can towards fees.

Joy has benefited from United Nations funding and aid from other donors. Most importantly, the centre has led the Ethiopian government to begin a programme for children with special needs.

'Possessed by the devil'

This does not mean there has been a tidal wave of sympathy in Ethiopia towards those living with autism.

Many people still think affected children are possessed by the devil because of their parents' sins. This could explain why autistic children are so often hidden.

The medical fraternity in Ethiopia is often equally ignorant. Elias Tegene, a psychologist who specialises in autism, describes the condition as a new "subject" that only became known in the past decade.

Despite the lack of official data in the country, he believes that rates are climbing rapidly.

Compounding the problem is the fact that many doctors working in Ethiopia have not heard of the condition.

Often those that recognise it either treat patients as psychiatric cases (when they are in fact neurological), or simply tell parents to discipline their children better.

From anecdotal evidence, Dr Elias believes autism to be most prevalent in the children of the so-called "boom generation" - those who have travelled abroad to work and study.

Nine-year-old Addis is one of these children. He was born in Maryland, in the US, to an Ethiopian family and diagnosed with autism when he was just over two years old.

His early diagnosis was due in part to the fact he was born premature at 27 weeks, and so was already being monitored by a medical team.

Life crammed with activities

Addis' father, Abiy, says that it took him and his wife a long time to accept the initial diagnosis.

"Everyone had a theory as to why this had happened and why it seemed that autism was more prevalent in Horn of Africa diaspora communities than in others. Someone told us that the children who were diagnosed back home [in Ethiopia] were those who had been born abroad in the US or in Europe," he says.

It was his wife, Azeb - a primary school teacher now specialising in special needs - who first suggested Addis was autistic. However, he resisted getting treatment for his son as he did not want to face the reality. The diagnosis prompted a long period of soul-searching.

Today, however, Addis leads a full life crammed with activities and has a particularly good sense of direction.

"My son is a great kid. If he had to have autism, so be it, but he is really the best son," says Abiy. "He is well behaved and has never held us back in any way."

While there is no research yet to support Dr Elias' view that autism is on the rise among Ethiopians, especially those living abroad, there is some evidence relating to Somali children in the diaspora.

In 2009 the New York Times reported that officials in the Minnesota Health Department in the US had agreed on a startling fact - that there are higher rates of autism in young Somali children in the state.

While stressing that this was a small sample, they stated that Somali children were two to seven times more likely to suffer from the condition than people from other ethnic backgrounds. There is also data from Sweden and elsewhere in the US that seems to support this.

Funding for research

Abdirahman D Mohammed - a family doctor at Axis Medical Centre in Minneapolis, who hails from Somalia - treats a wide cross-section of patients and has no doubt that autism is abnormally high in children of Somali origin.

_rt.jpg)

Zemi Yunus says that her son Jojo is a 'handsome young man, with lots of achievements'

"Unfortunately it's a huge issue for our community. It causes families great distress and anxiety," he says.

And because some people link autism with various childhood immunisations - which is questionable and has never been proved - some Somali children in the US are not being vaccinated against dangerous childhood diseases.

So why the strong prevalence in the Somali community? Dr Mohammed has no answers. "Is it environmental, genetic or both? We don't know. This is a great puzzle," he says.

Thankfully, the US Centre for Disease Control and Prevention has recently approved funding to research just this issue. Perhaps more needs to be done in Ethiopia and its communities living abroad.

Back in Addis Ababa, Mrs Zemi's son, Jojo, is now 20. She describes him as "a handsome young man, with lots of achievements." Recently he has started uttering some words. "He's on his way to talking, I'm so excited about it . . . he's coming on," his mother said.

It is stories like those of Jojo and Addis that provide hope for families living with autism.