Tales of success from Dadaab, world's biggest refugee camp

- Published

Dadaab refugee camp in north-eastern Kenya was set up in 1991 as a temporary solution to conflict in the Horn of Africa. Twenty years later its numbers are still growing and for many of the camp's younger residents it is the only home they have known.

The camp was built to house 90,000 refugees but its population is now broaching half a million people and with drought and famine ravaging East Africa, more arrive each day. Despite the desperation some residents are battling the odds, determined to make a success of life as a refugee.

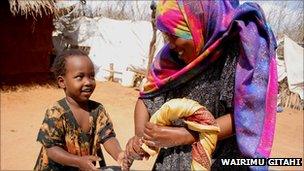

Bride-To-Be

Ardo Ahmed and her niece prepare for her wedding

Today at her parent's hut in Dadaab, Ardo Ahmed is caught up in flurry of activity. She was one of the first to arrive in the camp when her family fled Somalia in 1991. She was only five years old and caught up in the horrors of war.

But now at 24, she can put those memories aside and concentrate on a happier thought - her forthcoming wedding day.

Like many young women around the world, Ms Ahmed went through several relationships before meeting her fiance. They have been dating for two years and are now making the final preparations for their life together.

"Love is everywhere even in refugee camps - people think refugees are too desperate to fall in love but no, love is natural," she says.

"Refugees are also human, they fall in love, they have relationships, they get married, they have children."

"In this camp you often have weddings taking place. No matter where you are you will always find love."

As part of the ritual preparation, Ardo and her friends mix mud and plaster it on the walls to make them fresh and wash colourful curtains in a tub outside the house.

Miss Ahmed herself has much to attend to.

"In our culture, a woman preparing to get married makes her body attractive by applying henna on her hands and feet and wrapping in creams to soften her skin.

"I'll start doing those things tomorrow. I'll be spending most of my time indoors so I can concentrate on making sure I look nice on the day."

Miss Ahmed was only five when she left Somalia and can't remember much of her home country, but she still recalls what she saw of the war.

"I remember the gunshots and everything, I remember how some of our neighbours were killed in front of us," she says. "When we saw the blood around us our parents said: 'This is what war does to people.'"

They fled Somalia and arrived safely in Dadaab but they were not free from danger, it was a place where women were especially vulnerable.

"In those days we had to spend the night in the toilets, because there was much less security," she says. "We were scared of being raped."

When the camp first opened there were only three aid agencies looking after the rights of women and children. Now 28 groups operate, with many offering help to women and children, and security has vastly improved.

Miss Ahmed does dream of returning to her home country.

"Just because I am a refugee now, doesn't mean I will be forever. I have the hope of returning to Somalia one day."

Aspiring Journalist

Many refugees in the camp survive on money sent from relatives abroad

Among the wooden shacks and corrugated tin huts that line the dusty streets of Dadaab, shops peddle all manner of electronic goods and services.

In one of these huts, a young man sits at a computer updating his Facebook status and keeping on top of his emails.

Moulid Iftn Hujale is getting ready to leave Dadaab for the first time since he came from Somalia in 1999.

He recently won a scholarship to study journalism in Khartoum, Sudan but it has been a long struggle.

His arrival in the camp was one of the lowest points in his life.

"Our father died of a prolonged sickness, we could not take him to hospital, we fled from where we lived and were separated from our mother."

Arriving at the camp without his parents he faced stigma from people who assumed he and his siblings were orphans or abandoned children, born out of wedlock.

"But there we found peace, there was no gunfire and there was some sort of tranquillity," he says.

He was able to go to school and focused his energy on his studies. Three years later his mother made it to the camp. It was a dramatic moment, he remembers.

"My younger sister came to me in the school. I could tell that she had good news and immediately I saw my mother running through the main gate."

"My mum's tears were like water flooding and made my uniform wet."

Walking around the school where he spent his childhood he points to the trees under which classes were held.

"When it rained we could not learn under these trees.. We used to go home."

Now there is a huge tent to shelter children in the rain.

Mr Hujale is one of the few to head to university from Dadaab, but even with his good fortune the reality of being a refugee sometimes dawns on him.

"Living in Dadaab you can never forget that you will always be defined as a refugee," he says.

"If you are a degree-holder and living as a refugee in the camp, you can't get a job outside because you are a refugee. If you work in the camp you get paid very little money. It cripples our potential."

Tireless Doctor

Since February this year thousands of refugees have arrived at Dadaab every day. Gedi Mohammed, who works for Medecins Sans Frontiers, is on the front line receiving them as they arrive.

"If you are dealing with refugees who have walked thousands of miles to get here it will be difficult," he says. "By the time they get here they are almost dying."

"In the last few weeks we have seen a lot of insecurity cases, there are a lot of women that are raped on their way."

For the first two or three months doctors were working with the same resources as numbers at the camp tripled but now the conditions have greatly improved.

Dr Mohammed is a Kenyan Somali and is one of the few doctors who speaks the language of his patients and he talks to them with ease and familiarity.

"Initially when I came it was really difficult... especially with the new arrivals, [many of them] have never seen any sort of medical care in their life.

"But if you understand their culture you know their fears, so you try to educate them."

Life in the camp is gruelling for Dr Mohammed.

"When you're in the camp you are living with the same people you've worked with all day, when you are eating you are eating with the same people, you sleep in the same area. It's the same thing every hour."

When life is not so busy he tries to get some exercise, playing football with a local refugee team.

Dr Mohammed has worked in Dadaab a year and a half, far longer than most of his colleagues.

"In a crisis like it is now, it is really easy to give up. But if you think of all the positive things that you have done, it will make you stay more and more."

These interviews from Dadaab were first broadcast by Outlook for the BBC World Service. Listen to them here.