Uganda oil rush awakens hopes and fears

- Published

Residents of the sleepy village of Bugoma are wondering if they are about to be hit by an oil boom

As the water of Lake Albert laps at the shore of Bugoma village, some fishermen are fixing their nets.

Others are sheltering from the hot midday sunshine, sitting under the thatched roof of a mud hut near the lake.

This quiet fishing village has been here for longer than any of its inhabitants have been alive.

Nobody seems to know when it was first established.

Its future, though, is much more uncertain, because oil has been discovered under Lake Albert, the large body of water that straddles the border between Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Exploration work has already taken place, and full scale drilling is due to start within months.

Eviction fears

"Things don't look so good for us, the fishing community," says Gideon Kaiza, one of the fishermen.

"There's a man who came here and told us they'll be relocating us to another place because of the oil business."

"They want only a few people to stay," he says.

The men do not know exactly who told them to leave, but insist they and their families do not want to go.

Initially they did not think they would have to, as one oil firm, Heritage Oil & Gas, built a brand new school at the far end of the village.

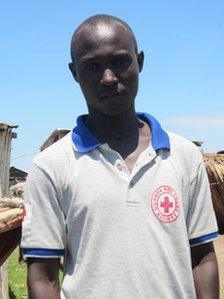

Fisherman Gideon Kaiza has been told he will have to move

"We knew that whoever had a house here would be given money if the government chose to relocate them, so that they start a new, better life with their families," says Mr Kaiza.

"In Buliisa, when the exploration started, everyone got paid," he adds.

"But here, there's been nothing, and yet we fear we're going to be evicted."

As he speaks, cows and goats lie around under the shade of a huge tree in the centre of the village.

Children, dressed mainly in old clothes full of holes, sit by the water's edge.

An hour and a half's walk away, up a steep hill and then along an uneven dirt road, is the nearest small town, Weragaza.

The sound from a film being shown in the local video hall can be heard on the main street.

Some boys are playing pool on a table, under a rickety looking canopy made of palm leaves.

In the town's bar, the elected chairman of the district, Omuhereza Rwemera Mazirane, says no-one will be forced from their homes.

"The land belongs to the people," he says.

"Anything which will be done, will be done amicably; we shall be sitting around the table."

"They cannot be moved without compensation."

Weragaza is surrounded by forest, which is home to monkeys and baboons.

Some of the nearby land is used to grow crops.

Mr Mazirane says the townspeople should be making more use of that to increase their incomes once the oil drilling starts.

"We are always encouraging our people to plant more crops, to produce more animals for future consumption by the people who are going to work in the oil industry."

He seems less convinced there will be lots of jobs available in the oil companies themselves, although he says a handful of people he knows already have jobs guarding oil sites.

Business opportunities

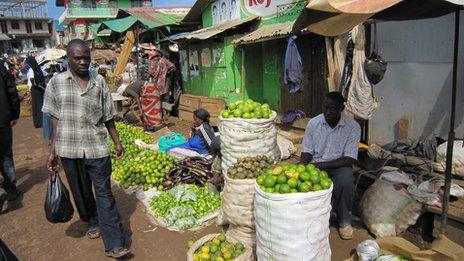

A three-hour drive away in Hoima, there is a much greater sense that people will benefit.

This is the closest big town to the oil fields, and its population is expanding at a fast pace.

On the edge of Hoima, a new guesthouse has just opened up.

Compensation has been promised, but local officials are urging people to look for business opportunities

Its owner, Trisa Kabaganda, apologises that she cannot show us any of her rooms.

She explains they are all occupied by men from Turkey, who are constructing a road towards the oil fields.

"This is the best place to open up a business."

"Hoima people have more of an advantage because it's the nearest town to the oil industry," she says.

"We are talking in the evening and are all of a sudden plunged into darkness as the power goes off.

"It happens every day," Ms Kabaganda says, adding that a nearby hydroelectric project is about to come online, thanks to the presence of oil companies.

"We are happy about that. Let's hope everything will change."

Ms Kabaganda also owns a takeaway restaurant in the centre of Hoima.

The plan for all of her businesses is to target oil workers to make sure she gets something for herself out of the oil wealth.

"I think within five years or so I should be a billionaire in Ugandan shillings," she says hopefully.

- Published3 November 2011

- Published31 October 2011

- Published12 October 2011

- Published26 April 2023