Nigerian leaders unite against same-sex marriages

- Published

Rashidi Williams: 'It's very difficult to live as a gay man in Nigeria'

Homosexual acts are already illegal in Nigeria. But for its lawmakers that doesn't appear to be categorical enough.

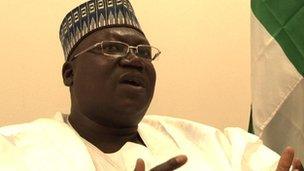

"This is to be pro-active so no-one catches us unaware," says Senator Ahmed Lawan, one of the backers for new legislation that would further criminalise Nigeria's gay community.

The Prohibition of Same-Sex Marriage Bill last week sailed unopposed through the Senate - the country's highest chamber.

Under the new bill, same-sex couples entering into either marriage or cohabitation would face jail terms of up to 14 years.

Those "witnessing" or "abetting" such relationships would also face custodial sentences, and groups that advocate for gay and lesbian rights could also be penalised.

'You are evil'

The lawmakers say they are simply reflecting the prevailing values of Nigerian society.

"We are protecting humanity and family values, in fact, we are protecting civilization in its entirety," Mr Lawan tells the BBC from his office in the capital, Abuja.

"Should we allow for indiscriminate same-sex marriage, very soon the population of this world would diminish."

Ahmed Lawan says both Muslims and Christians are opposed to same sex marriage

Far from being on the extreme fringe, the senator's views are moderate compared with some of his peers.

During the third reading of the bill, one northern politician said he believed the punishment should be death.

That was voted down, but at a tense public hearing at the National Assembly activists who spoke against the legislation were jeered and heckled.

"They said: 'You are evil, you are a devil, and if you were my brother you'd deserve to be killed,'" says John Adeniyi, one of those brave enough to speak out.

"And it made me feel like the world is not a place worth being in."

For most gay Nigerians, fear of the law and the depth of public hostility mean living openly is out of the question.

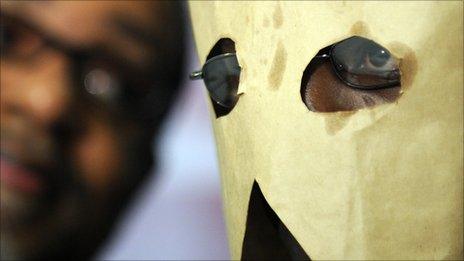

But Rashidi Williams, a 25-year-old from northern Nigeria, has refused to be silenced.

When we meet at a safe house in Abuja, he is wearing simple pink shoes and is frank about the abuse he has suffered.

"I have been attacked on several occasions," he says, telling me how earlier this year his collarbone was smashed when he was out walking with a male friend.

"Apart from that, you get verbal assaults every day, it's very frustrating."

Mr Williams now works for an organisation trying to protect the rights and health needs of homosexuals, bisexuals and transgender people.

UK-Nigeria row

It is the sort of group that could well be banned under the proposed legislation.

Nigeria is the latest African country to move towards restricting gay rights in recent years, following Uganda, Kenya, Ghana and Senegal.

Many traditional and religious leaders in Africa condemn homosexuality as unAfrican but there are also growing calls from activists across the continent for gay rights to be recognised.

And under pressure from their own electorates Western leaders are increasingly trying to exert their influence on proposals which they argue are against fundamental human values.

In October, UK Prime Minister David Cameron suggested that the aid budget could be cut to countries that didn't recognise gay rights.

Nigeria receives about £140m ($220m) a year from the UK, but - if anything - Mr Cameron's comments appear to have encouraged the Senate to show their independence.

"If there is any country that does not want to give us aid on account of this, it should keep its aid," David Mark, President of the Senate, proclaimed as the bill completed its third reading.

"We hold our values, customs and tradition dearly. No country has the right to interfere with the way we make our laws," he added.

Diplomats from the British High Commission in Abuja say they are watching the progress of the bill closely.

It is not hard to see what has so attracted the senators to the legislation.

In addition to thumbing their noses at an old colonial power, the bill also appears to be achieving that rare thing: Uniting the majority of followers of Nigeria's two main religions.

That is no small feat in a country riven by political and religious conflicts.

"Even though we are said to be secular by our constitution, Nigerians are very religious people," Mr Lawan says.

"Both Muslims and Christians are opposed to same-sex marriage."

But when speaking to Nigerian politicians, they keep returning to the same view - that homosexuality and hence same-sex marriage is alien to the country's history and culture.

It is a view that Mr Williams is quick to reject.

"We have traditional names for homosexuals. So tell me what is not Nigerian about homosexuality?" he asks.

"There is something very Nigerian about homosexuality, there is something very African about homosexuality."

Before it becomes law, the bill must be passed by the lower chamber, the House of Representatives, and then signed by the president.

- Published28 July 2023

- Published13 May 2011

- Published4 May 2011