Sirte and Misrata: A tale of two war-torn Libyan cities

- Published

All Sirte resident Hamid Mishri has left is a single mattress

Scrambling over rubble, Hamid Mishri picks his way through what is left of his house. Not much.

Something catches the elderly man's eye.

"Grad rocket," he says with a weary look, as he bends down to pick up a piece of twisted metal.

"Everything has been destroyed. I can't even shut my own front door," he adds pointing to where it used to be before it was blown of its hinges.

On the upstairs landing, there is a gaping hole where it looks like the rocket may have hit. The floors are littered with bullet casings. All the rooms have been ransacked and looted.

"They stole around 20,000 dinars, as well as my car."

All that is left is a single mattress, on which he sleeps with his wife and young son.

'Taking revenge'

Mr Mishri was a loser in the conflict in Libya.

He paid a price for living in Sirte, Muammar Gaddafi's hometown.

The city was pummelled by rebel forces in the dying days of the conflict, as the late Libyan leader made his last stand.

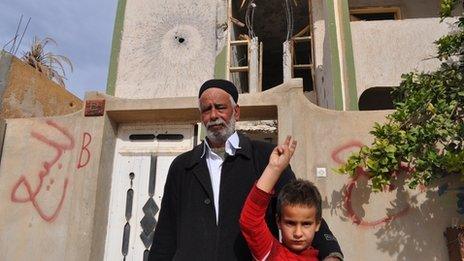

Just about every house in Mr Mishri's neighbourhood, which is known as District Two, has suffered some sort of damage.

"It's like they were taking revenge," he says, "and now the new government is doing nothing to help."

Like many people I meet in Sirte, Mr Mishri says he had no time for Gaddafi.

But amid the wreckage it was easy to find a few die-hard supporters.

"Gaddafi was protecting civilians here. Nato knocked down this city. Thousands were killed here," says Ali Naili, pointing angrily at the crumbling buildings.

"We're not prepared for justice or reconciliation until we know where the missing and killed people are, and where Muammar Gaddafi and his son have been buried."

Refugee camps

People in Sirte feel nobody is listening to them.

A day later, around 50 local people organised a small protest, blocking the main road towards Tripoli.

One of the demonstrators, who did not want to be named, told me he felt Sirte was being punished because of its history.

"I am sure of that. It's because Sirte is the hometown of the previous power. That is why nobody from the new government has visited us here," he said.

Muammar Gaddafi spent billions of dollars on Sirte; now it lies in ruins

I put it to him that most people in Sirte had been Gaddafi supporters.

"No. More than 40% of the people here were not with the previous regime," he replied.

But Sirte undoubtedly did well under Gaddafi's, who built it virtually from scratch around the small village where he was born.

Many key positions in the government and security forces were handed out to people from Sirte, be they members of the extended Gaddafi family or members of Gaddafi's tribe.

The colonel spent billions of dollars on infrastructure here, pampering his favourite city.

But large parts Sirte now lie in ruins.

Thousands of families, which fled during the fighting, are living in refugee camps outside the city.

They are not sure if they will ever be able to return home.

Rebuilding

Much of the damage, especially in District Two was inflicted by rebels from Misrata, the city that lies a few hundred kilometres to the west.

Fighters from the Misrata Brigades can now be seen patrolling the streets of Sirte.

Residents of Misrata are beginning to rebuild, unlike those in Sirte

Some in Sirte even told me they were living under a "Misratan occupation".

But of course Misrata also suffered too.

Earlier in the year, pro-Gaddafi forces terrorised the city, holding it under a violent siege for three months.

Hundreds of civilians were killed. There are also allegations of rape and torture by Gaddafi's men.

In Misrata, the damage is not as severe as in Sirte, but it is still substantial.

A museum has been built in Libya to remember rebels from Misrata who died in the conflict

On Tripoli Street, where some of the fiercest fighting took place, many buildings are burnt out and potted with bullet holes.

"The regime destroyed all the stock and all the shops," says grocer Isadeen Suessi in his tiny shop that sits precariously under a badly damaged block of flats.

His brother was killed by Gaddafi loyalists during the fighting.

But unlike many people in Sirte, Mr Suessi has already started to rebuild.

"The shop was looted during the uprising but now I have all new stock and business is getting better and better."

Trophies

And the mood in Misrata is generally much more upbeat.

They know they came out on the winning side.

The city has opened a war museum. When we were there was full of its full of visitors.

It is full of memorabilia, including the famous statue of an iron fist crushing an American warplane which once stood in Muammar Gaddafi's Bab al-Aziziya compound in Tripoli before it was carted over to Misrata as a trophy.

There is also testimony to the former Libyan leader's eccentric and eclectic fashion sense - a pair of pink leather winkle-picker shoes along a Russian-style fur hat.

But the museum is also been built to remember those who died.

The walls are lined with hundreds of photos of Misratan rebels who were killed. Everyone here says their young men did not die in vain.

And winning seems to have made it easier to forgive.

On the edge of the city, I meet Adel Mugazbi a chunky and cheerful former rebel.

"I was too fat to fit in a tank, so I helped provide the catering during the war," he laughs.

He's clearly upbeat, and like many in Misrata he plays down the tensions with his neighbours.

"We can have good relations with Sirte. The fighting before was just 'blah blah blah'. Sirte is part of Libya now."

But back in Sirte, graffiti daubed on a wall tells a different story. It reads: "Misrata, brothers never."

The vast majority of Libyans believe the country is now a better place without Gaddafi. In Sirte, they are not so sure.

In the new Libya will the losers have a say?