Bird flu empties South Africa's ostrich farms

- Published

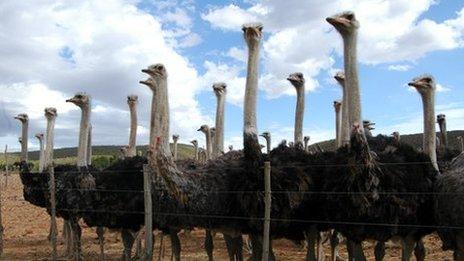

South Africa's population of more than 200,000 ostriches is the world's largest

South Africa's ostrich farmers are struggling to cope after thousands of their birds were culled during one of the country's worst outbreaks of bird flu.

Exports to Europe - the biggest market for South Africa's ostrich meat - have crashed since the EU banned the import of the low-cholesterol meat to stop the virus spreading.

Some farmers have been able to salvage their business through exporting ostrich feathers to South America - they are used in the colourful Rio Carnival.

Oudtshoorn, a town about 450km (279 miles) from Cape Town, is the heartland of the country's ostrich industry.

Highgate Ostrich Show Farm is empty, apart from a few workers cleaning the yard there is no-one else in sight.

This is uncharacteristic of the popular tourist farm which is always abuzz with activity.

Hundreds of local and international visitors would normally be queuing to ride trained ostriches, buy luxury ostrich products such as leather and feathers or simply to spend time feeding the birds.

But for the first time in its 80 years, there are no ostriches for visitors to see - they have all been culled.

"When the virus was discovered on our farm a few months ago the authorities came and took away all our birds," Arenhold Hooper tells me.

His ostriches were among 40,000 ostriches killed in the area, believed to either have the virus or have come into contact with infected birds.

All the meat was thrown away.

Mr Hooper is a fifth-generation ostrich farmer. He says he had to fire all his 38 employees and close the farm - he and his workers are now unemployed.

Ostrich feathers are often used to make costumes for the Rio Carnival

The Highgate farm workers have more than 130 dependants between them and they are desperate to earn a salary again.

"It all happened so fast we didn't even have time to prepare our staff for what was happening," he says.

The ostrich industry in this area is responsible for the direct employment of 20,000 people.

"It has been a frustrating time for all of us. Our first priority now is to get birds back on the farm so I can bring back all my employees and we go back to earning a living," says Mr Hooper.

But that will not be for some months.

He has been barred from re-populating his farm until the ban is lifted even though he is not a meat exporter.

Officials cannot say if the virus poses a threat to humans but they are not taking any risks - so for now all birds are considered potentially dangerous.

Feather fashion

Across town, I met Zackie Jonker, the head of Ostrich Products South Africa - one of the largest ostrich product exporters in the area - and discussed his plight over lunch.

All the food orders from the tables around me featured ostrich in some form.

I seemed to be the only one anxious about my food - it would be my very first ostrich steak.

It was soft and full of flavour, just as Mr Jonker had assured me.

It is this taste that has made it popular in places like Europe, which consumes 90% of the low-cholesterol beef-like meat, according to the South African Ostrich Business Chamber, a group regulating trade in this industry.

Mr Jonker breeds thousands of ostriches on a number of farms in Oudtshoorn and has lost 6,000 ostriches because of the bird flu.

But he is trying to recoup some profits by exporting ostrich leather and feathers to South America, the US, Europe, China, Korea and Japan.

His company generates 60% of its export income from feathers and leather and 40% from meat.

"Our ostrich feathers are incredibly popular in South America where they are used in costumes for the Rio Carnival, haute couture, clothing and feather dusters. We have fortunately been able to retain some revenue through that," explains Mr Jonker.

But not a lot of farmers have access to this luxury market - so being able to export meat again is a priority.

Vendors in the Western Cape use ostrich feathers to make dusters

To slaughter or not to slaughter?

South Africa's ostriches are bred mainly in two provinces - the Western Cape and the Eastern Cape.

In Oudtshoorn alone 150,000 birds are reared in an area measuring over 20,000 sq km (7,722 sq miles).

With each passing month the industry is losing 108m rand ($13m; £8.2m).

The Western Cape Department of Agriculture and Rural Development says the disease seems be under control for now.

But it adds that more tests are being done on the thousands of ostriches in this region.

"We need to continue running tests until none of the ostriches test positive and we need to maintain this for three months, only then will the ban be lifted and the markets opened again," the department's Wouter Kriel told the BBC.

In the meantime, farmers have been offered some money as compensation for their loss but all involved agree that the money is not enough to cushion the blow to their business.

But those who still have healthy ostriches are urged to slaughter them for the domestic market, to try and prevent the disease from spreading.

"It is not as good as the money they would make if they were exporting their meat but it is better than nothing," explains Mr Kriel.

Although the farmers are against this idea, with the costs of caring for the birds piling up this seems likely to be the only option for the 300 or so farmers for now.

But experts say even if the ban on meat exports is lifted in the next few months and the region declared "clean" - it will take up to four years for the industry to recover from the effects of the outbreak.

- Published23 October 2011