Libya economy banks on cash for recovery

- Published

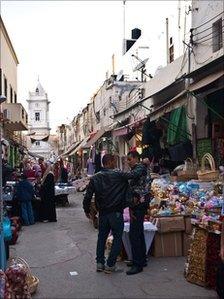

Shop owners at this market are getting their businesses up and running again

In Martyrs' Square in Tripoli, the symbolic centre of Libya's uprising, the facade of the National Commercial Bank still bears the marks of fighting.

The bullet holes are a stark reminder of Libya's recent conflict. But inside, queues emphasise the impact the fighting is still having on the country's economy.

One customer waits patiently at the broken counter window to withdraw his salary. Queuing behind him, there are close to 100 people, all trying to do the same thing.

On another long counter, arms stretch over as customers battle to deposit their cheques that the bank clerk duly stamps. Few words are exchanged. Here, it is all about dealing with the deluge.

Since the fighting began, Libya has been strapped for cash, with billions of dollars of assets frozen in foreign bank accounts.

Banks limited the amount of money that customers could withdraw to 750 dinars ($600; £400) a month, and although there are signs that this limit will be raised, it has made things difficult for people trying to access funds and rebuild their lives.

Most customers wait without complaint, but one man, about the 20th in line, starts to shout. He is blaming the Western banks for hanging on to Libya's money and causing the country's cashflow crisis.

"They haven't given our money to us. Why?" he asks. "Gaddafi has gone. But now we are still living in the crisis, deep in the crisis. It's worse than before."

Assets are slowly being returned. Last month, the UN Security Council lifted sanctions on Libya's central bank and its foreign investment bank.

That cleared the way for billions of dollars to be unblocked abroad. The US and the UK followed suit soon afterwards, but still, billions more remain outside of Libya.

Customers face long queues at the banks to get their money out

This piecemeal unfreezing of assets is still not quick enough for many here. They say they are not seeing the benefits from this, nor from money coming in from Libya's rapidly-recovering oil industry.

"We're now selling over a million barrels a day - that's $100m (£64m) a day," says Sami Zaptia, the managing director of consultancy firm Know Libya.

"It's a question of where is the money going? Is Libya paying off some debts? Are we paying Nato? What's happening? It's big money."

As Libya makes the transition to a new government, tensions are not just confined to the banking system.

This week, workers at Tripoli's port went on strike demanding better working conditions and an end to corruption. They want some management staff, who they claim are Gaddafi loyalists, to go.

And the country is still dealing with big security threats. Four people were killed this week after clashes between militia in the capital. It is these sorts of incidents that make it difficult for Libyan businesses to get back on their feet.

Struggling businesses

Just off Martyrs' Square, in the capital's old medina and central market, is Motaz Buhajar's gold shop.

Before the fighting, he had 15 outlets in across Tripoli, Zawiya and Misrata. He closed all but one because of security concerns, and the remaining branch is struggling.

"We're only opening to be in the market," Mr Buhajar says. "People are going to buy milk, sugar and all that stuff. Nobody's focusing on buying gold."

While he thinks his business will take another six months to recover, across the way is another shopkeeper who seems to be doing much better.

Every bit of wall in Alsadeq Altomey's wedding shop is stuffed with gold, purple and pink brocade. And he has a steady stream of customers coming in to try and find that perfect wedding outfit.

It is a big change from last year.

"In Ramadan, we only worked in the morning - then part-way through Ramadan, the situation got tense and we had to close more regularly," says Mr Altomey.

"Now it's 100% better. Weddings are resuming now and the parties are on again."

Despite the challenges, the sense of determination is clear. Back in the gold shop, a customer arrives.

Mr Buhajar says no matter what the challenges are, his country is fiercely proud of what has been achieved. Life needs to continue, he adds.

"We have to act as normal to give the impression to the world that we are breathing as Libyans."