Senegalese President Abdoulaye Wade's rise and rule

- Published

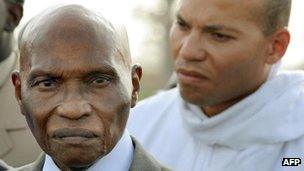

Abdoulaye Wade, 85, puts his good health down to his love of swimming

After four unsuccessful attempts, Abdoulaye Wade was first elected as president in 2000 - ushering in much-needed political change.

Despite fears that his re-election bid could threaten Senegal's stability, the 85 year old has accepted defeat in the presidential run-off.

A lawyer and economist, Mr Wade had been the main opposition leader for almost 30 years, fighting against the one-party system in place since the country's independence from France.

Senegal's independence-era leader and poet Leopold Sedar Senghor nicknamed him "The Hare", an animal known in traditional Senegalese folklore for its cunning.

Jailed

According to official records, Mr Wade was born in 1926 in Kebemer, about 150km (95 miles) north of the capital, Dakar. But some say his real birth date was several years earlier.

After completing secondary school in Senegal, he was awarded a scholarship to study in France, where he met his wife, Viviane.

After returning home, Mr Wade created the Senegalese Democratic Party (PDS).

The PDS joined forces with several other opposition parties to form a coalition to challenge the ruling Socialist Party (PS).

Defending democracy and a free-market economy, the coalition was named "Sopi", a word meaning change in Wolof, the country's most widely spoken language.

Considered a shrewd politician and very good speaker, he fought his way through four presidential votes between 1978 and 1993 - first against Mr Senghor, then against Mr Senghor's political heir and Socialist leader, Abdou Diouf.

Mr Wade was arrested and jailed several times for his political activities, but also served twice as minister under Mr Diouf.

Wade: The Senegalese people is a free people. It will decide if I have to two mandates... or five mandates.

While the country was waiting for the results of the 1993 election, Babacar Seye, vice-president of the country's constitutional court in charge of approving the results, was assassinated.

Mr Wade and some of his allies were accused and charged with plotting against state security.

The charges were later dropped and Mr Wade always denied responsibility.

Three hitmen were convicted of the murder but many Senegalese remain convinced that the full truth has not yet come out about one of the ugliest incidents in the country's history, especially after Mr Wade pardoned the assassins in 2002.

'Old man'

In February 2000, the Sopi coalition finally prevailed.

Mr Wade was elected president with around 60% of the votes and the crucial support of another opposition leader, Mustapha Niasse - who had come third in the election and was rewarded with the post of prime minister.

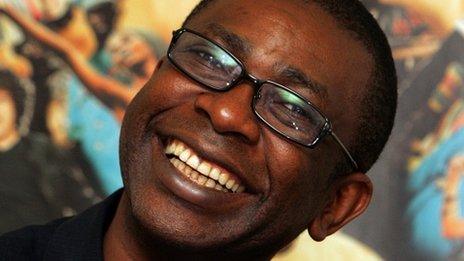

The new president - affectionately known by his supporters as "Gorgui" or old man - embarked on a wide-ranging modernisation programme - building schools, health facilities, improving access to drinking water and launching an ambitious agricultural programme.

He also diversified Senegal's financial partners, moving away from a dependency on France and striking agreements with countries such as China and Dubai.

But what Mr Wade's supporters praise as his vision and statesmanship, his critics see as a tendency towards megalomania or autocracy.

His decision to commission from North Korea a 50m (164 ft) high bronze monument to the African Renaissance was heavily criticised in a country where poverty is still rife and electricity scarce.

For Mr Wade's opponents, the statue - so high it can be seen from anywhere in Dakar - summarises the current regime in Senegal: Expensive, useless, pretentious and hollow.

He was also one of the prime movers behind the New Economic Partnership for Africa (Nepad) - a vision of transforming Africa which resulted in endless speeches and meetings around the continent but little else.

Two-term limit

Corruption and nepotism at the top are cited among the most serious problems in Senegal.

After he was re-elected in 2007, Mr Wade, who says his good health comes down to his love of swimming, said he would not seek a third term.

Abdoulaye Wade (l) has been accused of grooming his son, Karim, (r) to succeed him

A constitution was adopted in 2001 that sets a limit of two presidential terms.

But the president now argues the provisions of the current constitution do not apply to his first mandate - because it came into being after he was first elected.

Public dissent has been mounting since June 2011, when Mr Wade tried to have the constitution amended again - to lower the threshold for the president to be elected to 25% of the votes.

The bill also proposed an US-style presidential ticket that, opponents say, would have enabled the president to choose his successor.

He has been accused of grooming his son Karim, 43, for the presidency - he is already a "super-minister". Both men deny the charges.

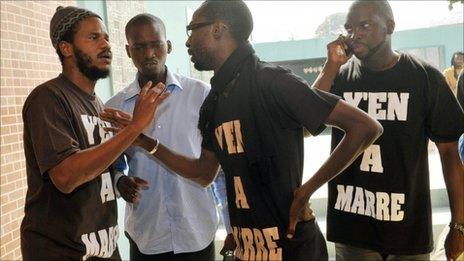

In the face of massive street protests across the country organised by the 23 June Movement (M23), he withdrew the proposed changes.

Mass protests

M23 is once again trying to mobilise the population to prevent Mr Wade's re-election.

There have been demonstrations over Abdoulaye Wade's third-term bid

Over 12 years, Mr Wade's rule has gone from mass celebrations to mass protests.

In previous elections, leaders of Senegal's influential Mouride Islamic brotherhood have endorsed Mr Wade but not this time.

Several former allies have become opposition leaders and four former prime ministers or ministers are running against Mr Wade.

After Mr Diouf accepted his defeat to Mr Wade in 2000, Senegal was hailed as a model for democracy in West Africa and remains the only country in the region never to have had a military coup.

Many Senegalese and foreign observers had feared that if the president did not agree to withdraw his candidacy, the very fabric and stability of Senegal could be at risk.

But in the event his graceful acceptance of defeat seems to have been another advance for the country's democracy.

- Published31 January 2012

- Published5 January 2012

- Published5 August 2011

- Published9 July 2024