Invisible Children's Kony campaign gets support of ICC prosecutor

- Published

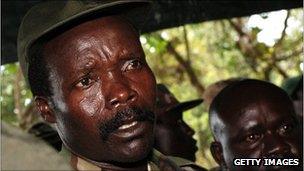

LRA rebel leader Joseph Kony is wanted by the International Criminal Court

The International Criminal Court's chief prosecutor has said he supports a new campaign to capture alleged Ugandan war criminal Joseph Kony.

Louis Moreno Ocampo said the social media campaign by Invisible Children had "mobilised the world".

The US group's <link> <caption>half-hour film</caption> <url href="http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y4MnpzG5Sqc" platform="highweb"/> </link> on the use of child soldiers by Kony's Lord's Resistance Army has been viewed nearly 20 million times on YouTube.

However, critics have questioned the campaign's content and credibility.

The group aims to bring Kony to justice at the ICC, where he is charged with crimes against humanity.

But bloggers accused Invisible Children of spending most of its raised funds on salaries, travel expenses and film-making.

Some local journalists and activists in Uganda have also called the campaign "patronising", while analysts have said it fails to fully reflect the reality on the ground.

The ICC's chief prosecutor Luis Moreno Ocampo has defended the "Kony 2012" creators.

"These are just a bunch of kids from California, they could be off surfing or whatever but they're not," he said.

"They're giving a voice to people who before no-one knew about and no-one cared about and I salute them."

Mr Ocampo appears in the Kony 2012 campaign video.

Viral voice

Speaking from his office in The Hague, Mr Ocampo said he believes this viral strategy could assist in the fight for international justice.

"The world reacts when Adolf Hitler is committing crimes or Gaddafi but no-one knew Joseph Kony because he is not killing people in Paris, or London, Germany or New York... but Invisible Children care and they've mobilised the world now."

Joseph Kony and his close aides have been wanted by the ICC in The Hague since 2005.

Their campaign of terror began in northern Uganda more than 20 years ago when they said they were fighting for a biblical state and the rights of the Acholi people. It now operates primarily in neighbouring states.

The group is notorious for kidnapping children, forcing the boys to become fighters and using girls as sex slaves.

US President Barack Obama in October 2011 announced he was sending 100 special forces soldiers to Uganda to help track down Kony, but so far he has managed to evade international justice.

So can a social media campaign succeed where others have so far failed?

Kony 2012's creator Jason Russell said it can: "It's a new world and people in the institutions need to catch up... We're at a place in time where human beings can collectively leapfrog a system. There's no army in the world that is more powerful than this idea."

'Famous to who?'

It is of course impossible to capture all the elements of such a complicated conflict in a 29-minute film.

Since it was posted there have been thousands of re-tweets of articles highlighting some of the nuances that exist that the film fails to capture.

Even academics have been sharing their thoughts, with some saying the campaign fails to accurately represent the roles played by both the LRA and the Ugandan government forces and thus gives a distorted picture of what is going on in the country.

Meanwhile, some Ugandans say the whole premise of a movement to "make Kony famous" is patronising to people in the country who are well-aware of the rebel leader's existence and to other charities and NGOs who have spent decades trying to stop the LRA.

Ugandan journalist Rosebell Kagumire tweeted: "They want to make Kony famous, famous to who? We have seen the burial ground mutilated children etc."

Speaking to me from her home in Kampala, Rosebell said she did not know "how this fame is going to turn into something tangible for people suffering on the ground".

People power

But it is the utilisation of social networking, using virtual people power to try to affect change in real global issues, that really makes this campaign so worthy of attention.

The video spread at speed on Twitter, quickly becoming the biggest trending or most talked about topic on the site.

Celebrities such as Rihanna, Oprah and P Diddy re-tweeted the "Stop Kony" message to their millions of followers.

But could social media really be the future of international justice?

"I guess if you get it to the right people and the right person latches onto it," said Chad Bilyeu, a social media expert based in Amsterdam.

"It's this passive mode of revolution these days where a retweet is rebellion."

What the Kony 2012 campaign has undoubtedly done is show how to communicate a basic message to inspire mass action.

The question of whether such a simple social media message can really make a difference to such a highly complex conflict may only be answered if and when Joseph Kony is brought to The Hague.