African viewpoint: Yellow fever and family demands

- Published

- comments

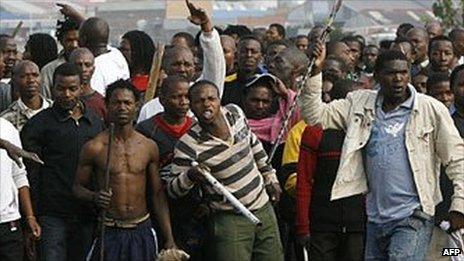

There have been several recent outbreaks of xenophobic attacks in South Africa

In our series of viewpoints from African journalists, Nigerian writer Sola Odunfa reflects on the rise of xenophobia in post-apartheid South Africa, following the recent repatriation of a group of Nigerians, accused of having fake yellow fever vaccination certificates.

One of the trickiest problems that confronts a young couple is their relationship shortly after the wedding.

This is especially the case when the man is the financial cornerstone in his family.

The family expects him to continue to support them exactly as he used to before his new status as husband and, therefore, head of his own nuclear family.

Brothers and sisters

If he fails to live up to their expectations they turn on his wife - and accuse her of trying to turn their son against his brothers and sisters.

On her part, his wife reminds him constantly of his new responsibilities in the home and cautions that a line should be drawn somewhere between his family loyalty and the needs of his own home.

It takes wisdom and diplomacy for the man to navigate his way through these conflicting demands.

Otherwise he risks either destabilising his home or incurring the anger of his siblings and larger family.

Neither augurs well for his, and his children's, long-term happiness and well-being.

In the apartheid years, South Africa was the rallying point of almost all black African nations.

They all saw it as their political and moral duty to join in the battle for the liberation of their oppressed brothers and sisters.

At the time when the entire West was, at best, indifferent to the struggle, African nations flexed their diplomatic muscles at every international forum against the operators of white racial supremacy and their supporters.

Some of them went as far as giving both economic and military support to South Africa's freedom fighters, especially the African National Congress (ANC).

Some South Africans have campaigned against xenophobia

At the forefront of this effort were the countries of east and southern Africa - which became known as the Frontline States.

Nigeria - despite being far away in the west - also contributed financially and diplomatically - and so was embraced as an honorary Frontline State.

The anti-apartheid struggle created a unique relationship between South Africans and virtually all other Africans.

They became brothers and sisters in the real sense.

It was not surprising when after the victory over apartheid, there was an influx of Africans into the new South Africa.

But trouble began.

The jobs available could not go round. South Africans blamed immigrants for taking their jobs and they became hostile.

Their brothers from Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Nigeria and other African nations became targets of insults, physical attacks, police harassment and mass deportations.

Yellow fever row

The climax for Nigeria was the refused entry on 2 March of a planeload of Nigerians.

South Africa's immigration officials said their yellow fever certificates were fake - but they did not produce any evidence for their conclusion.

Nigeria responded, pronto.

South Africans were turned away at Lagos airport - those working in Nigeria suddenly faced a lot of questions over their immigration papers.

Passion was so inflamed that some Nigerians even urged their government to start demanding certificates from travellers from South Africa to show they were clear of HIV/Aids.

Their, misplaced, argument was that South Africa was a major centre of the epidemic - with infection rates running at about 11% nationally - whereas yellow fever had been eradicated in Nigeria.

Luckily, common sense prevailed on both sides very quickly, within six days.

The two governments are now reconciling - but the same cannot be said of the citizens.

The diplomacy will somehow have to be extended beyond the politicians and technocrats - if the true meaning of brotherhood is to be appreciated once again.

Post-apartheid xenophobia cannot yield good fruits.

Some years ago Nigerians were shouting "Ghana Must Go" as they harried Ghanaians in droves out of the country.

Now Ghanaians are comfortable at home but Nigerians are seeking economic exile in that country.

No condition is permanent.

If you would like to comment on Sola Odunfa's latest column, please use the form below.