Sand and fury: Mali's Tuareg rebels

- Published

- comments

In the vast emptiness of the Sahara, an obscure war is underway

How much more obscure can a war get?

Deep in the Sahara desert, in the vast emptiness of northern Mali, several hundred rebel fighters have overrun, and outmanoeuvred a small number of army garrisons, external.

So what, you might ask?

So a lot.

The humanitarian impact of the conflict is already being felt not just in Mali, but in neighbouring Mauritania, Burkina Faso, Algeria and Niger, as tens of thousands of civilians - many are nomads, but that's beside the point - flee the fast spreading insecurity that has erupted close to Mali's borders.

The refugees are putting extra pressure on communities already struggling with high malnutrition rates and the likelihood of a devastating "hunger season", external in the coming months.

As for the Tuareg rebellion itself - it has evolved into more than a purely local quarrel.

Its latest eruption is a direct consequence of last year's events in Libya. Some Tuareg tribesmen fought alongside Muammar Gaddafi's troops. Others may have fought with the opposition.

They have since returned home, armed to the teeth with looted weapons, and seemingly determined to transform a half-hearted rebel movement into a serious - if probably unrealistic - drive for an independent Tuareg state, which they call Azawad.

The rebels are a coalition of different factions and agendas united under a new name - the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA). In a complex environment, the catalytic factor appears to be the arrival of so much new weaponry from Libya.

"Why do we need to fight for independence? We already own the desert," a Tuareg friend of mine in Timbuktu grumbled down the phone this week.

It is not clear yet how much popular support the rebellion enjoys.

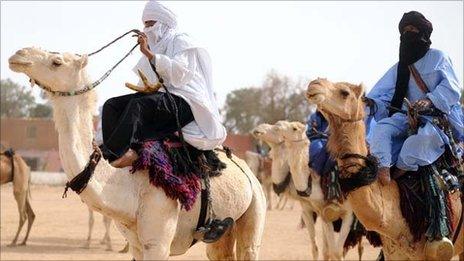

But the Sahara is not what it used to be. As the world has found quicker, cheaper ways to move goods around the continent, the Tuareg and their increasingly redundant camel trains have been left to survive on the dregs - gun-running, drug smuggling, and ferrying would-be immigrants north towards Europe.

The fighting has forced many thousands from their homes

And now even the tourist trade has been taken from them. Al-Qaeda's local affiliate (Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb; AQIM), external has found that the desert makes a convenient place to hide and to raise money.

The extent and nature of AQIM's links to the MNLA is hotly disputed - some Tuareg groups appear to be close, financially if not ideologically, to the Islamist militants.

But al-Qaeda's presence and its growing appetite for kidnapping foreigners for ransom have left the region even more isolated.

AQIM's influence can now be seen in Algeria, Mauritania, Niger and Nigeria.

As for Mali itself, the rebellion is aggravating old tensions between northerners and southerners to potentially explosive levels.

The army's military failures against the MNLA rebels could also have serious political repercussions, not least on the upcoming presidential election, scheduled for next month.

President Amadou Toumani Toure insists he will still step down as planned, but analysts and diplomats are quietly starting to wonder whether the generals will allow him his dignified departure at such a precarious moment.

Foreign interest in Mali's future extends far beyond the crackdown on terrorism and smuggling in the Sahara, with rich gold, oil and uranium deposits at stake.

- Published29 February 2012

- Published24 February 2012

- Published17 October 2011

- Published18 September 2011

- Published4 March 2011

- Published28 July 2023