Joseph Kony victims back online campaign

- Published

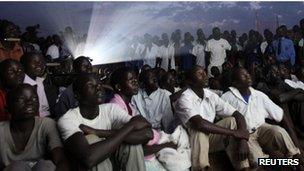

Some South Sudanese have already taken up arms against Kony and the LRA

With a controversial US film putting the spotlight on Ugandan rebel leader Joseph Kony and his Lord's Resistance Army, the BBC's James Copnall reports on those in South Sudan and Uganda who believe he must be captured or killed at all costs.

In a refugee camp in the shade of giant mango trees, a Congolese man called Jean-Roger is calling for US soldiers to capture the leader of the Lord's Resistance Army, Joseph Kony.

"We need a military intervention. [President Barack] Obama must make an effort to finish with Kony," he says in a firm voice.

"The LRA has killed a lot of people, and raped a lot of women, and they kidnap children to train them to become like them. They must be stopped."

The recent <link> <caption>Kony 2012 film</caption> <altText>Kony 2012 film</altText> <url href="http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y4MnpzG5Sqc" platform="highweb"/> </link> , which has been viewed millions of times, has attracted criticism for simplifying the problem of the LRA.

But Jean-Roger and other victims believe the only thing that matters is to stop the rebel movement.

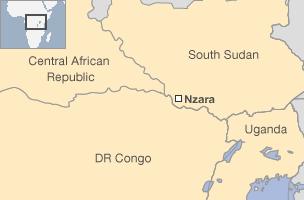

There are more than 5,000 refugees in the Makpandu camp in South Sudan, the majority from the Democratic Republic of Congo, others from the Central African Republic.

Those are the two countries where the LRA now operates, though its fighters - many of whom are children - sometimes launch raids into South Sudan too.

'World must act'

Another refugee, Modeste, a grey-haired man with a bright floral shirt, also wants foreign troops to help out.

His four daughters, aged between five and 14, were kidnapped when the LRA attacked his village in DR Congo.

"I think they must be dead," he says simply, perhaps not wanting to voice the other, horrifying prospect - that they have been kept as sex slaves.

"I want governments all over the world to act, we must finish the LRA. The world should get enough forces to attack, and kill all of them," he says.

A short walk away, Jeanne is preparing dinner in front of her simple thatched hut. She will grind groundnuts into a paste, and add some cassava leaves.

She is wearing a camouflage top, giving her a strangely military appearance - a bitter irony considering it was the LRA's fighters who drove her from her home.

Screening of the Kony film was abandoned in Uganda last week

"Some of the people from my village were killed, and I don't know what happened to the others.

"If the LRA can be stopped, we can return to Congo. But I don't know when it will happen."

Although the Kony 2012 film has prompted renewed calls for action against the LRA, several forces have been fighting them for years.

The LRA is no longer in Uganda, but the Ugandan army is chasing after them from bases in South Sudan and the Central African Republic (CAR).

The Congolese, Central African and South Sudanese armies are involved too.

But not always with much success.

The LRA's current strength is estimated at a few hundred, but they still terrify many times this number.

"We receive regular refugee arrivals due to ongoing LRA attacks in Congo and CAR. They (LRA) also conduct hit-and-run attacks inside South Sudan," says Mireille Girard, the head of the UN refugee agency in South Sudan.

'Arrow boys'

In the South Sudanese state of Western Equatoria, some residents have taken matters into their own hands.

A dozen men brandish their weapons - one AK-47, some old rifles they describe as "home-made", and the bows and arrows that have given them their name, the Arrow Boys.

In June last year they rescued two people, including a 13-year old girl kidnapped by the LRA from the village of Kidi, about 12km from the town of Yambio, close to the DR Congo border.

That incident was the last time the LRA struck in South Sudan, but their impact over the last few years has been dramatic.

"The damage Kony has inflicted on our people in Western Equatoria is actually far greater even than the losses that we incurred during our 22 years of civil struggle with the Khartoum government," says Sapana Abuyi, the deputy governor of Western Equatoria.

It is a startling statement. Two million people are estimated to have died during Sudan's second civil war, although Western Equatoria was less affected than other parts of South Sudan.

The frequency of LRA attacks has now fallen in South Sudan, in part due to the efforts of the Ugandan troops, and the Arrow Boys.

But Mr Abuyi is still wary.

"We cannot rule out more attacks, because they use guerrilla tactics and they can hit at any time."

US role

He also calls on the US advisors to the Ugandan troops to do more, particularly in tracking the movements of the LRA fighters, who often operate in small groups in the forest.

So far the Americans, who number 100 throughout the region, are there to advise not fight, following President Barack Obama's directives.

So what can the Americans do, if they are not allowed to go into combat?

"Primarily, our advice and assistance is along the lines of planning the fusion of operations and intelligence, logistics planning, and bolstering their communications," the US team's leader Capt Layne told the BBC.

Hunting Kony in a region as heavily covered by forest is akin to "looking for a needle in a haystack" according to the captain.

Would he prefer to kill or capture Kony, who is wanted by the International Criminal Court?

"As long as we rid the region of Joseph Kony, we're happy, however that happens," he says.

Col Joseph Balikudembe is the Ugandan who is leading Operation Lightening Thunder against the LRA.

The Ugandans have not yet got hold of Kony despite a quarter-century of efforts, but the colonel is still optimistic.

"His time is numbered, he will be captured," he says.

"It took time to capture Osama Bin Laden, but eventually he was killed. Kony will have his time too."

The senior officer denies charges made by some campaigners that the Ugandan military has kept the war running for so long as it justifies high military spending and allows officers to make money from the conflict.

The Kony 2012 film, made by the US campaign group Invisible Children, has shone an unprecedented global light onto the LRA.

It has been heavily criticised in some quarters.

"In elevating Kony to a global celebrity, the embodiment of evil, and advocating a military solution, the campaign isn't just simplifying, it is irresponsibly naive," regional expert Alex de Waal wrote.

Dialogue

Bishop Eduardo Hiiboro Kussala has campaigned against the LRA for many years.

He supports the film as a way of raising awareness. But he believes the military option is not the right one.

"When we talk about a military intervention, people who think they are powerful think it is the only way to solve a problem.

"They think that by the gun you can solve the problem, but instead you aggravate it.

"To me military intervention is not a solution. I would encourage dialogue."

In a camp for South Sudanese displaced by LRA attacks near the town of Nzara, that view would not be supported by everyone.

"The LRA don't want to see you as a human being,' says Charles. "If they see a human, they kill him with a machete or shoot him with a gun. That is why we fear them."

Some of the displaced people here have begun to return home. But many remain.

"If Kony is arrested, that can solve the problem," says David, hurrying through his words in his anxiety to stress the point.

"The abduction of the children and the killing of people make us afraid, that is why most of the people don't want to go back to our homes."

These people have not seen the Kony 2012 film. But they are vociferous in their demand for Joseph Kony to be stopped by any means necessary.