African viewpoint: All hype, no justice?

- Published

- comments

Some people in northern Uganda found the Kony 2012 video exploitative but other victims in South Sudan agree with the campaign

In our series of viewpoints from African journalists, film-maker and columnist Farai Sevenzo considers whether the scales of international justice are really balanced.

It is never dull on this continent of ours: In just two weeks we have rediscovered Uganda's Lord's Resistance Army (LRA) in a deluxe new generation video and we have heard that, after 10 years in existence and spending nearly $1bn (£631m), the International Criminal Court (ICC) have finally delivered their first guilty verdict.

A couple of weeks back I was having an email conversation with our 15-year-old son - all aboutthe YouTube video that has placed Uganda's dead conflict with Joseph Kony's LRA back on centre stage, externalwith the slickly produced awareness campaign Stop Kony 2012.

Have you seen it, he wanted to know.

It is difficult enough I'm sure to rouse teenagers from their weekend slumber to discuss a lunch date never mind a 26-year-old African conflict.

Like an old hack I dived into the debate with my man child.

"Don't believe the hype," I said. "You must learn to think for yourself - where does the money go?

"There are far more informative videos by real journalists on YouTube,including one made by your old man, externalin Kitgum, Lira, Gulu, the Ugandan-Sudanese border which tells the real story of the LRA and I would post that on Facebook if I were you."

And, in general, that was the spine of much of the criticism surrounding the video that unhelpfully wanted "to make Kony famous" by publicising a conflict that is no longer in Uganda itself - as it has moved to the Central African Republic (CAR), the Democratic Republic of Congo and South Sudan - and by promising to do something about Mr Kony's murderous existence, if the youth would only buy some "Stop Kony" bracelets and engage with the notion that there was "nothing more powerful than an idea whose time has come".

Of course, my son disagreed. It was all over Facebook and he had no intention of appearing all "non-conformist" and rubbishing something that had stirred his Facebook friends into engaging with the real world of conflict in Africa like never before.

Potential voters

And so a divide was formed among the 80 million people or so who had watched the Stop Kony campaign, comprising those who thought it a good idea to mobilise the digital generation of 14 to 24 year olds into lobbying their governments about the need to end Mr Kony's horrific exploitation of children who were just like them, regardless of where Mr Kony now currently resides.

Lubanga, 51, faced two counts of war crimes for enlisting child soldiers under 15 to fight for his militia

In two weeks, the Stop Kony campaign created a forest fire of mutterings about sentimental exploitation, new missionaries and the white man's inclination to play the saviour of Africa's peoples through condescending and patronising depictions of our suffering.

None of this was helped by the news that the director and voice of the campaign, Jason Russell,Kony 2012 video director detainedwhich led him to run around San Diego streets, in the US, acting strangely while dressed only in his underwear.

What about the people whose story is irrevocably linked to the LRA's reign of terror?

It is easy to sit in any city in the world and imagine that the cyber world is as common as oxygen, and that even Mr Kony must now know how famous he has become. Not so.

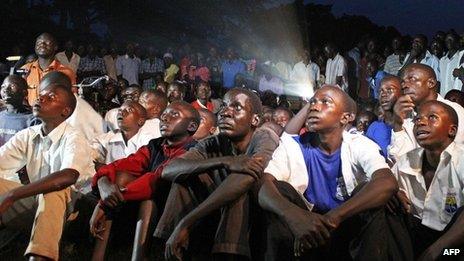

The people whose suffering gave genesis to Invisible Children Incorporated had not seen the film that was arguably fast becoming more famous than Joseph Kony and when a local charity showed it to them their reaction was surprisingly hostile - not to the devil they knew in Mr Kony - but to the people they said "were making money out of their tragedy".

And Mr Kony himself has no satellite phone that can be tracked to the outskirts of CAR or the jungles of DR Congo and the International Criminal Court has had a difficult time trying to arrest him while little was said of the scores of children still to be freed from the LRA.

But something had happened and that was that the idealism and humanity of very young people was harnessed by social media to condemn the wicked acts of a forgotten warlord.

And politicians - as they are wont to do - could only ignore these huge viewing figures of potential voters at their peril.

A beast with teeth?

The ICC, meanwhile, found a Congolese militia leader - Thomas Lubanga - guilty of recruiting child soldiers in the first conviction of the court's 10-year history.

Much has been said about the ICC's perceived bias against Africa - thousands of communications about crimes against humanity in more than 139 countries are known to have been received by the court's prosecutor Luis Moreno-Ocampo and yet the vast majority of investigations and public warrants of arrest are against Africans.

From Lubanga to Jean-Pierre Bemba, DR Congo's ex-vice-president, and the Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir the court is accused of making great examples of Africans when the world we live in sees many war crimes elsewhere and the most powerful nations are not even signatories to the ICC's Rome Statute.

Our relationship with this court will remain complex, but should Lubanga's fate not be applauded for marking our intolerance to the practice of turning children into soldiers?

Graca Machel - Nelson Mandela's wife and a long-time campaigner in this cause - said of the verdict: "Those who engage in these practices should not only be treated as pariahs in this world but they must be hunted down, tried, convicted and given the maximum sentence. It is abhorrent that individuals like Lubanga will use children as cannon fodder to do their bidding in a selfish drive to control resources for personal gain."

And that was essentially the message of the Kony 2012 campaign which seemed to have got get lost in its own hype.

And so we learned this week not to shoot the messenger and that the ICC is a beast with teeth that can sometimes bite but we have no idea who is holding the beast's leash.

If you would like to comment on Farai Sevenzo's column, please do so below.