Gaddafi's influence in Mali's coup

- Published

Some analysts say the coup may have been spontaneous not planned

It did not take long for the Libyan conflict to spill over borders in the Sahel region - and now Mali seems to have paid the highest price so far following a coup by disgruntled soldiers.

The trouble began when hundreds of Malian combatants who had fought to defend the late Libyan leader, Muammar Gaddafi, fled back home with weapons at the end of last year and formed the most powerful Tuareg-led rebel group the region has known - the Azawad National Liberation Movement (MNLA).

Mali's Tuaregs have long complained that they have been marginalised by the southern government and have staged several rebellions over the years.

Joined by young recruits and former rebels who had been integrated into the Malian army in recent years, the MNLA fighters took over several key northern towns in just two months.

Not only did they secure a large stretch of territory in the mountainous desert but they also triggered the mutiny, which later turned into a coup, in the capital, Bamako, on Wednesday night.

While the Malian government had been busy claiming the situation in the north was under control, rank-and-file soldiers felt humiliated and abandoned in combat with not enough military resources and food.

"The Libyan crisis didn't cause this coup but certainly revealed the malaise felt within the army," says Malian newspaper columnist Adam Thiam.

"President Amadou Toumani Toure hasn't been active in tackling drug trafficking and al-Qaeda fighters, and the emergence of new rebel movements only added to the soldiers' frustration."

Anger 'too high'

It is hard to tell whether these mutineers had planned to oust President Toure.

After weeks of growing discontent, it seemed a rather spontaneous mutiny when soldiers expressed their anger during a visit by the defence minister to a military barracks on Wednesday.

It escalated quickly and it is possible that mutinous soldiers organised for the coup "as the day unfolded", according to Mr Thiam.

Talking to the BBC on the condition of anonymity, a government official said, however, that "nobody could now pretend they were not warned".

"Many within the government felt something could happen, we just didn't know when and how. The anger was just too high," he said.

Nearly a month before a presidential election, and at the end of President Toure's second and last legal term, this coup is a 20-year jump backwards for Mali.

In 1991, Mr Toure, then an army general, put an end to a military regime in a coup.

As promised, elections were held a year later and Mali started building on democratic fundamentals.

Mr Toure came back to power through elections a decade later, in 2002.

The vast West African country has since become one of the rare examples of democracy in the region.

Despite pride in their democracy, some have pointed out that there has, so far, been very little sign of condemnation from Malians.

But the way in which President Toure's administration handled the crisis in the north of the country had already sparked anger beyond the army's ranks.

Hundreds of people set up barricades and burned tyres in the streets of Bamako last month - protesting at the government's inability to repel northern rebels.

"This coup tarnishes the country's image as it only illustrates how the military has yet to accept the superiority of civil actors in many African countries," says Abdul Aziz Kebe, a specialist in Arab-African relations at the University of Dakar, in Senegal.

"Regional institutions are weak because member states have weak institutions," he adds.

The West African body Ecowas has, among others, condemned the mutineers' takeover.

Earlier in the week it had urged member states to provide military equipment and support for the Malian army to help it quell the Tuareg insurgency in the north.

But analysts say it was doubtful that Ecowas states would have sent any reinforcements or agreed to deploy the organisation's force, even though it is meant to intervene in such circumstances.

They point to the fact that Ecowas failed to take action in Ivory Coast last year to help solve that country's violent post-electoral crisis.

'No interest in Bamako'

In the meantime, rebels from the MNLA say they might "benefit from the situation".

"It's always best that this corrupt government is toppled," said Hamma Ag Mahmoud, speaking from the Mauritanian capital, Nouakchott, where the MNLA has its political wing.

Mr Mahmoud served as a minister in the military regime of Gen Moussa Traore before it was overthrown by Mr Toure.

"We will certainly advance southwards to continue to liberate the Azawad," he says, referring to the northern region the MNLA wants to become independent.

"We're not interested in Bamako, but Kidal, Timbuktu and Gao. These mutineers will not have the firepower to resist against us. They will have to sign a peace agreement at some point."

A rebel officer in Tessalit, a village in northern Mali under MNLA control, said: "The only thing that could threaten our advance is a foreign intervention."

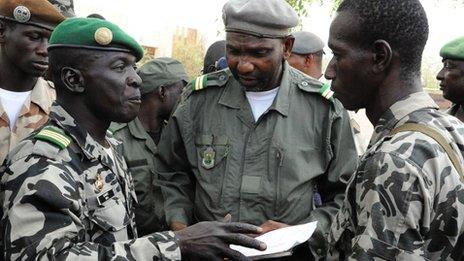

The Malian army says it has not had enough weapons to take on the rebels

Some Malian officials have blamed Nato for the crisis in the north after it helped Libyan insurgents topple Col Gaddafi.

"Western powers have underestimated that getting rid of Gaddafi would have severe repercussions in the Sahel region," Mr Kebe says.

Northern Mali has long become a rear base for drug traffickers, al-Qaeda fighters and other Islamist combatants sharing ground with Tuareg rebels.

Heavy weaponry and arsenals left over from the Libyan war simply reinforced their positions.

Seizing power will not change the extreme difficulty of the army's task as it attempts to combat all of the above.