Can Charles Taylor verdict heal the horrors of war?

- Published

Edward Conteh describes the day his arm was amputated by RUF rebels

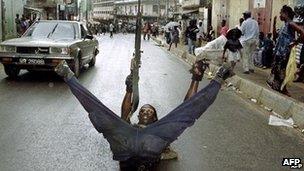

A signature atrocity of the rebels that overran Sierra Leone in the 1990s was the chopping off of limbs with a machete or axe, often by child soldiers.

"They caught me and stamped on my chest," Edward Conteh told me.

"I had gone out to try to find food for my children. We hadn't eaten in three days.

"One of the rebels brought an axe and chopped off my left hand - not in one blow. It took five or six."

Mr Conteh is now the chairman of the Amputees' Association, which campaigns for help for those left limbless.

"It is my strong conviction that everything that happened to Sierra Leone is down to Charles Taylor," he said, referring to the former president of neighbouring Liberia, who is awaiting Thursday's verdict in his war crimes trial in The Hague.

"I heard him on the radio threatening to make Sierra Leone taste the bitterness of war. Well we tasted it," he said.

Mr Taylor is accused of arming and funding the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) rebels, led by Foday Sankoh, who died in a Sierra Leonean prison cell awaiting trial.

The indictment sheet against Mr Taylor accuses him of crimes against humanity, mass killings, sexual violence, abductions and the use of child soldiers, all of which he denies.

He has been on trial for four years. If convicted, it will be the first time a former head of state has been found guilty of war crimes by an international court.

Complacent?

"Most Sierra Leoneans believe that without Charles Taylor in power in Liberia, there would not have been a war in Sierra Leone," Information Minister Ibrahim Ben Kargbo told me.

"It is no secret that we Sierra Leoneans see Charles Taylor as the man who actually encouraged Foday Sankoh to spread his violent activities.

"Now that Charles Taylor is out of the way, we can easily and safely say that with his absence we are beginning to enjoy peace without having to look over our shoulders."

Many see this as complacent.

The war had its roots in the failure of the post-independence Sierra Leonean state.

Successive post-colonial governments plundered the country's resources, corruption was widespread and poverty deeply entrenched, especially among the rural young.

But 10 years after the war ended, you sense the wheels of recovery starting to turn.

I have visited Yonibana, a village about three hours' drive from the capital, Freetown, several times.

It is home to about 4,000 people, most of them living in thatched huts of mud brick.

Rebels tore through here in an orgy of looting and burning. Many of the houses that were destroyed have yet to be rebuilt.

Nothing much happens or changes in Yonibana.

The RUF rebels got into the heart of Freetown

There is no economy to speak of - the young are educated in the local school but there are no jobs waiting for them at the end.

Now that looks likely to change.

The son of a former paramount chief, Rev Sulaymani Kamara, told me the local authorities have just signed a huge development contract with a Chinese company.

The plan, he said, is to build a rubber plantation, a pineapple plantation, and rice fields to supply resource hungry China.

The ground here is fertile, and water is plentiful.

Rev Kamara believes it will be one of the biggest single investments in Sierra Leone since independence and that it will bring thousands of new jobs.

Outside Lunsar, a town bitterly fought over during the war, there is more evidence still.

Rich reserves

The London Mining Company has reactivated an iron ore mine that has been derelict since the 1960s.

With international companies investing in Sierra Leone, there is hope the country can build on its peace

It started producing ore again in December. The company says iron ore reserves here will last 25 years.

"The first phase will last four years," the mine manager Gerhard Hermann said.

"We have recruited between 1,200 and 1,400 workers for that.

"But the second phase will last 20 years, and we'll need a much bigger workforce for that."

Slowly, too, Sierra Leoneans are rebuilding the institutions of democratic accountability.

Since the war ended there have been two successful and transparent elections.

Four years ago, the incumbent government lost and left office peacefully, willingly, and unmolested.

A tented settlement that once housed amputees in Freetown is now a wasteland football pitch

"Democracy in this country is secure," said Mr Kargbo.

"This government came to power after winning an election, removing an incumbent government. It does not normally happen in many parts of Africa."

Another election is due in November.

"If you lose it," I asked him, "will you give up power or try to cling on?"

"We will go, of course, we are not going to be like Laurent Gbagbo!" he said, talking about the ousted president of Ivory Coast who is, himself, now awaiting trial in an international court.

The streets of Freetown will await the Charles Taylor verdict eagerly.

For Sierra Leoneans, the trial has been a way of coming to terms, of making sense of the catastrophe that befell them.

It is another milestone on their long journey back from the horrors they lived through.