My verbal sparring with Charles Taylor

- Published

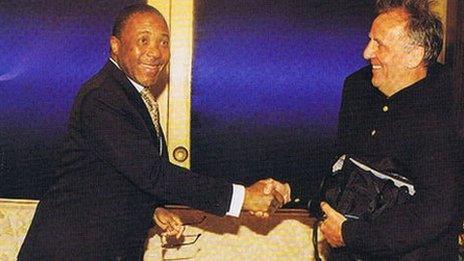

Robin White finally met Charles Taylor in 2000

A UN-backed war crimes tribunal has convicted Liberia's former President Charles Taylor of aiding and abetting rebels in neighbouring Sierra Leone. He first came to international prominence after an interview on the BBC's Focus on Africa programme with its then editor Robin White, who looks back at Charles Taylor's rise and fall.

New Year's Days are usually a bit thin on news and much of the discussion in the Focus on Africa office on New Year's Day 1990 was along the lines of "how on earth are we going to fill the programme?"

And then, Charles Taylor called.

He claimed to have invaded Liberia and was on his way to Monrovia to overthrow President Doe.

I'd never heard of Taylor, or his Patriotic Front movement but he sounded plausible.

Liberia was not a happy place to be in 1989.

It had been run for the previous 10 years by Samuel K Doe, an illiterate army sergeant who ended more than 100 years of rule by the True Whig party - by parading government ministers through the streets of Monrovia, naked, and then shooting them dead on the beach.

Doe was incompetent, brutal, tribalistic and possibly cannibalistic. He rigged an election and locked up the opposition. Unsurprisingly there had been several attempts to get rid of him.

So Charles Taylor's call was not a total surprise.

Charles Taylor in 1991: "There will be no ceasefire"

I interviewed him and we put him on air. The rest, as they say, was history.

The Focus on Africa radio programme broadcast on the BBC World Service became the focal point for the coverage of Liberia's chaotic civil war.

Everyone wanted to be on the programme.

Scarcely a day went by without a warlord or a government spokesman or a peacekeeper or an eyewitness calling us to ask that their voice should be heard.

Flamboyant and clever

I thought and, I think many Liberians thought, that Taylor's war would be short, sharp and successful.

He had the backing of Libya's Colonel Muammar Gaddafi and some of Liberia's near neighbours.

Charles Taylor spent eight years fighting in the bush

He had money, guns, and ammunition and, at first, considerable popular support.

But it took him more than eight years to make it to the presidency - by which time thousands had died and the country lay in ruins.

Charles Taylor's appeal was obvious.

He was the complete opposite of Doe: Flamboyant, clever and well educated.

And, above all, he could talk.

Liberians love a talker and he was the mother of all talkers. He was the "Liberian Lip"; the "Monrovian Motormouth".

He knew how to deal with the media.

He never held a press conference unless he had something important to say.

He never called us if he didn't have a story to tell - and he rationed his appearances.

Many listeners think that he was constantly on BBC Focus on Africa bragging about his latest successes.

In fact, during those many years of war, he only phoned six times.

Taylor's progress was at first dramatic. He took Nimba country and then moved on to other targets like the vital iron mining town of Yekepa.

His army grew. He was endorsed by prominent Liberians abroad such as Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf, Liberia's current president.

Monrovia beckoned.

But then his advance stalled.

His Patriotic Front movement split down the middle after he quarrelled with Prince Johnson, the man who finally killed Doe.

And other liberation movements, like Ulimo, sprang up to muddy the waters.

Ecomog, the West African peacekeeping force, moved in to try and establish some kind of order and Taylor was left stranded in his regional capital, Gbarnga, pretending to rule half of the country.

Pyrrhic victory

Umpteen peace conferences later, Taylor finally got his prize - he won the 1997 presidential election.

But it was a pyrrhic victory.

Liberia had been destroyed and the people demoralised.

He had no money and he was an international pariah. He needed money to finance his private army, the Anti-Terrorist Unit.

But he couldn't beg or borrow - so he had to steal.

He chopped down Liberia's forests and shipped off timber to Marseilles, and he flogged off any minerals and diamonds he could lay his fingers on.

It did him no good.

Already copycat rebel movements like Lurd were on the march and, like Taylor before them, were calling us at Focus on Africa to claim military successes.

The writing was on the wall.

I first met Taylor face-to-face in the Executive Mansion in Monrovia in 2000.

Charles Taylor in 2000: "No-one can ever claim that diamonds, as tiny as they are, can be controlled."

He could still talk the talk, but in person he is not so impressive: Small, slightly moth-eaten, with not very well designed stubble on his face.

He denied masterminding the RUF rebellion in Sierra Leone and rejected American claims that he was dealing in "blood diamonds".

He told me: "There is a satellite over Liberia every 48 minutes. The United States can take a picture of a matchstick or even a safety pin. But they don't have any evidence of anything".

But the connections with Sierra Leone were obvious.

Amongst the praise singers milling around Taylor in the Executive Mansion when I was there were RUF supporters who made no attempt to hide their identity.

Taylor loved danger, loved plotting, loved scheming, loved meddling.

It's hard to believe that he didn't have some finger in the Sierra Leonean pie.

But the abiding mystery for me is this: Why has Charles Taylor been tried for what he did in Sierra Leone? Why is he not held to account for what he did to Liberia and Liberians?