Viewpoint: Africa must do more to profit from China

- Published

- comments

Chinese businesses are viewed with mixed feelings in the region

Chinese investment in Africa has escalated rapidly over recent years, but what are the implications of China's foray in the continent, asks expert in China-African relations Solange Guo Chatelard.

China is an economic powerhouse with long-term ambitions in Africa. Like Brazil, Russia and India, it is here to stay.

Asking whether China is good or bad for the continent is not only beside the point, it distracts us from more pressing and relevant questions, such as what do African states want to gain from these new partnerships, and what are they doing to achieve this?

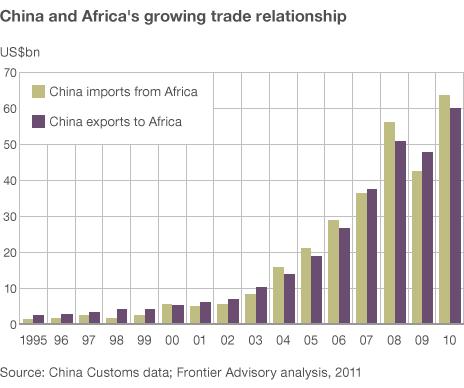

China is now Africa's largest trading partner, surpassing the United States and its traditional European partners. Commercial ties between the two regions exploded since 2000, leaping from $10bn (£6.3bn) to over $100bn in the last decade.

The towering new African Union headquarters in Addis Ababa was a largely welcomed $200m gift from Beijing and a clear testimony of China's intention, and ability, to engage with individual states as well as an entire continent, presenting it with new opportunities and challenges.

The intensification of economic ties has led many critics, chiefly based in the West, to question China's motives.

Investment welcomed?

While some argue that China is a 21st Century partner for development and a unique catalyst for growth, critics fear that China is a new colonial power, plundering Africa's natural resources and exacerbating existing patterns of corruption and inequality.

Advocates claim that China's rise has benefited the continent by injecting unprecedented investment, dynamism, and confidence into local markets, generating important gains for local economies. Critics, in contrast, accuse China of violating local laws, depleting the continent's resources, and taking advantage of corrupt leaders.

Despite mounting criticism and the Western media's largely negative portrayal of events, reality on the ground reveals that, by and large, both African governments and people welcome investment and new partnerships with the Asian giant.

"If you want concrete things you go to China. If you want to engage in endless discussion and discourse you go to the normal traditional donors," a senior manager from United Nations Economic Commission for Africa put it bluntly.

However, these partnerships are not without problems and are far from the shining examples of south-south cooperation Chinese leaders and media often like to portray.

'Not homogenous'

The truth of the matter is, China's involvement in Africa is not a black and white affair. In fact, most of it is grey. Very grey.

To begin with, "China" does not operate as a bloc. "China" in fact is composed of a myriad of private investors, state agencies and hybrid actors that spend more time in Africa competing with one another than worrying about Communist Party slogans.

The Chinese in Africa are not a homogenous and cohesive community organised along nationalistic lines as is commonly perceived by outsiders.

Zambians explain how Chinese investment and trade are affecting their livelihoods

Instead they are a mixed bag of ordinary men and women willing to endure hardship to improve their fate despite the cultural and linguistic challenges they face. As such, they are similar to the growing number of Africans who move to China each year in search of a better life.

In addition, the continent is not one single "actor". Each African country has its own particular set of engagements with China.

While everyone seems to know what China wants from its counterparts, less is said and known about what African countries want from China.

The self-proclaimed champion of anti-Chinese sentiment, Michael Sata, changed his tune when he was elected president of Zambia in 2011, learning to accommodate the Chinese rather than expel them as he once threatened in a previous election campaign.

But has Zambia identified a strategic partnership that will enable it to reap the full benefits of Chinese trade and investment?

Lessons for Africa?

China has opened up new economic, diplomatic and strategic avenues for African states, but it is ultimately down to Africans, both the people in power and the man on the street, to negotiate on their own terms, identify priorities, and leverage opportunities to further their own interests.

Contrary to prevailing views, China is not offering a "model" of development. It has no quick-fix recipe for success. Although China is making it possible for Africans to visit, study and work in China, it is not asking, or requesting, other countries to emulate it or support its values.

Since the 1990s, however, China showed that with clear political goals and strong regulation of foreign investment, it could leverage natural resources and low labour costs to develop its economy. The key was letting people get on with it.

It may be too early to call China's economic miracle a success story, or determine how many African countries are willing, interested or indeed capable of following a similar course, but for the first time since the end of the Cold War people from Algeria to Angola have a genuine alternative to the Western donor bloc.

If there is one thing African states can learn through China, it is how to imagine their own future, explore new possibilities, and engage with the rest of the world while retaining control over the conditions of those engagements.

<italic>Solange Guo Chatelard is a PhD candidate at the Institut d'Etudes Politiques de Paris and an associate at the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology in Germany.</italic>

- Published3 November 2011

- Published23 December 2010

- Published9 December 2010