What Burundi could teach Rwanda about reconciliation

- Published

Rose Hakizimana's mother and four sisters were killed by Burundian Hutu rebels while they were housed in a camp for ethnic Tutsis forced to flee their homes.

She remembers finding her mother's body by identifying her legs. For a full year after the burial she had nightmares.

When people think of genocide in Africa, neighbouring Rwanda usually comes to mind after the slaughter of some 800,000 Tutsi and moderate Hutus in 100 days in 1994.

But over the years Burundi, which has a similar ethnic make-up and tensions, has also faced killings by both Tutsi and Hutus, driving a wedge into the fabric of the nation.

The most shocking was in 1972, when some estimate up to 300,000 Hutus were massacred in six weeks.

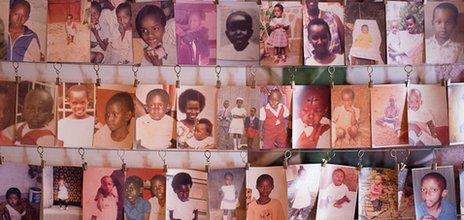

Ms Hazikimana has kept an album documenting acts of genocide in 1993 in which some 25,000 Tutsis are believed to have died, so that the crimes are not forgotten.

She went on to become an MP in the transitional government that brought peace to Burundi.

Now retired, she has a regular slot on local radio as a political commentator and says ethnicity is no longer an issue in politics.

"If you look at the current situation in the country, though we have a Hutu-dominated government that is not the problem," she told the BBC.

"What we are seeing now is a government that is not against Hutu or Tutsi, but a government that targets individuals who don't agree with their policies."

Her comments reveal how Burundi is now coping with ethnicity far better than its better-known neighbour.

First Hutu army chief

This may be down to the Arusha Peace Accord, brokered by South Africa's former President Nelson Mandela.

Signed in August 2000, the ceasefire led to talks that eventually helped end the long, drawn-out conflict and got politicians from both sides of the ethnic divide talking - it put ethnicity centre stage.

The accord recognised the tensions between the dominant Tutsi minority and the Hutu majority as a catalyst to the conflict and came up with a 60-40 formula of proportional representation.

Two years ago, ex-rebel Godefroid Niyombare became the first ever Hutu army chief of general staff.

According to President Pierre Nkurunziza - a former rebel Hutu leader who came to power in the first democratic elections in 2005 - this new-look army is a testimony to reconciliation efforts.

"The base of our problems during former times were the army and the police - now we have both ethnic groups represented," the president told the BBC.

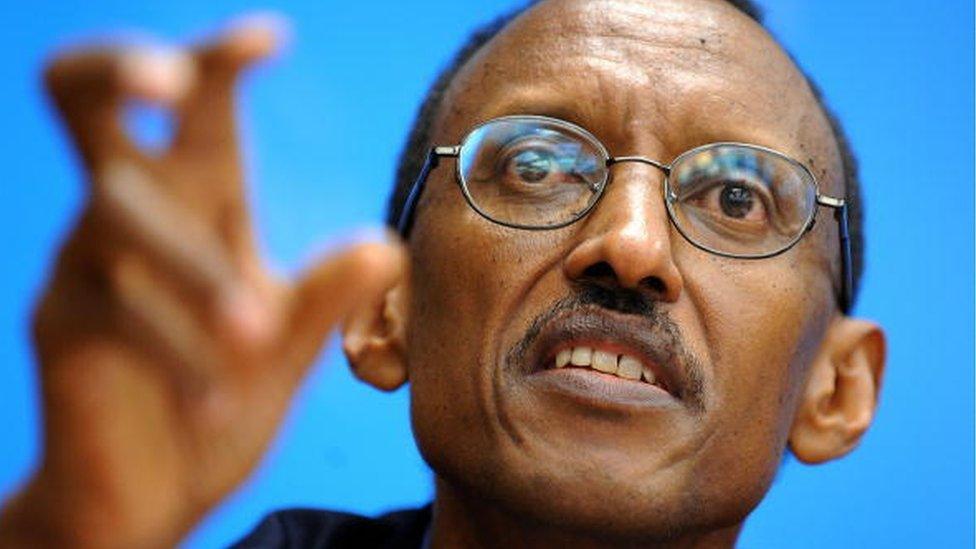

Such a comment from Rwanda's President Paul Kagame would be unthinkable, as tribal references are banned and considered tantamount to a denial of the genocide - a criminal offence.

A Rwandan opposition leader is currently on trial for propagating ethnic hatred because she has questioned why the official memorial to the 1994 genocide only mentions the Tutsis killed, not the Hutu victims.

Mr Kagame says such strong-arm tactics are needed to prevent a repeat of the massacres, but his critics say he is only keeping a lid on the tensions, which could boil over.

Ethnic jokes

In Burundi where it was once also a taboo to mention ethnicity, politicians now make light of their ethnic differences in public debates, something analysts say has contributed to the healing process.

Rebuilding and reshaping Rwanda

For example, traditionally Tutsis, who reared cattle, were thought to drink more milk than Hutus, who were farmers.

So a Tutsi might jest with a Hutu colleague who reaches out for the milk during an office tea-break: "You Hutus, you want to drink all the milk now."

Such banter, even in a bar, would be careless talk in Rwanda that could land you in jail.

This is not to say that Rwanda is not witnessing some reconciliation.

The show village of Bugesera, outside the Rwandan capital of Kigali, is an example.

Set up by a non-governmental organisation to show that enemies can live as neighbours, it has been Laurence Niyongira's home for the last 10 years.

The killers of her family are not only her friends, but people she now refers to as family.

Her neighbour's husband organised the killing of her family - a fact both families cannot hide.

"[But] we have reached reconciliation and have forgiven each other," she admits - words often repeated from other Bugesera residents.

Truth and reconciliation

Rwanda has also made much more progress when it comes to seeking justice for genocide victims, setting up community "gacaca" courts which tried close to two million people for their involvement.

Unlike Rwanda, Burundi does not have that many visible massacre memorials

In contrast Burundi has been slow in setting up national institutions to deal with the crimes committed.

But the government hopes that once there is funding and systems in place they will be able to let justice take its course - a Truth and Reconciliation Commission has been promised.

And unlike its neighbour, the symbols of reconciliation are not many or that obvious.

There is a mausoleum in the capital, Bujumbura, to remember Melchior Ndadaye - the first democratically elected Hutu president, who was assassinated in October 1993 by Tutsi soldiers.

Melchior Ndadaye was Burundi's first democratically elected Hutu president - assassinated in 1993

A similar monument honours independence hero Louis Rwagsore, a royal prince who won respect from both the Tutsi and Hutu communities.

But the ethnic divide that Burundi experienced - with Tutsis dominating every sphere of society and neighbourhoods split along ethnic lines - is all but over.

Burundians consider themselves to be free and are confident that their country will not be torn apart by ethnic enmity again.

Human rights bodies like Amnesty International laud Burundi for embracing democracy and having a much better grasp of it than Rwanda.

For Ms Hazikimana, who knows that the former rebels now in power killed her family, the root cause of the misdeeds of Burundi's past was never ethnicity.

"Burundians never hated each other. It was all about politics and done for political gain. Politicians used money to convince people to carry out crimes and killings."

- Published17 May 2011

- Published3 August 2017

- Published16 July 2024

- Published4 November 2022