Why South Africans risk death and injury to be circumcised

- Published

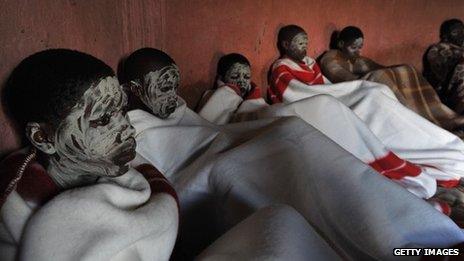

Circumcision is seen as a rite of passage into manhood by some South African ethnic groups. Males who have not undergone the ritual are not considered real men; they are ridiculed and ostracised.

This is why thousands of young men and boys risk injury and even death to undergo the procedure during "inititiation schools" in the bush.

"All the boys in my class had been circumcised and they bullied me and made me feel worthless because I was still a 'small boy'," said an 18-year-old from Qumbu village in Eastern Cape province.

"I felt pressured to go to the bush because that was the only way they would respect me."

He went to a circumcision school without his parents' knowledge - something he says he now regrets.

Lying on a hospital bed in the town of Mthatha, where he has spent two months already, the teenager says he was repeatedly assaulted, starved and refused water by the man in charge of the school.

Some traditional surgeons believe that torturing initiates will make them strong men.

The initiate is one of 300 boys rescued from illegal schools in the impoverished province between June and August.

Many were found near death and treated for dehydration, sepsis and gangrene, health officials told the BBC.

'Dying like ants'

"After about a week in the bush, I started losing weight and became really weak. I noticed that my penis had become swollen," said the teenager, who asked not be named because he feared being victimised.

"I was taken to hospital where it later fell off because of the severe infection."

Nurses said he had suffered a "spontaneous amputation" due to gangrene.

The practice of ritual circumcision is common among ethnic Xhosas and Ndebeles - two of South Africa's most numerous communities.

Traditionally young boys would spend an average of six weeks in a secluded area in the mountains away from prying eyes.

There, they would be taught the virtues of discipline, courage and how to be reputable men in society.

South Africa's circumcision season is June and July and November and December.

About 20,000 initiates go to initiation schools during each of these seasons, according to the Eastern Cape Department of Health.

While many initiates visit well-established schools, hundreds fall prey to bogus surgeons each year.

"Many of the iincibi [traditional surgeons] today are untrained and are not qualified to perform the circumcision," says Chief Jongumhlaba Hlangu, a traditional leader in Nqgeleni, a village a few kilometres outside Mthatha.

"The practice has become a way for chancers to make money."

In a nearby hospital, a mother is in tears as she strokes her son's head. He is still frail following months of treatment for a septic circumcision which also resulted in a penile amputation.

"Our children are dying like ants. I want the people doing this to be arrested and punished," she says, angrily.

Botched circumcisions have led to the deaths of more than 240 boys - some as young as 13 - in the last five years, officials say.

Despite the many deaths and horrific tales of abuse, the police say it is difficult to make any arrests because communities and initiates refuse to come forward with information.

'Cultural purists'

"The custom is ruled by secrecy. I don't want any more deaths in my village but I feel helpless because the community does not want to get involved in helping us catch these people," says Chief Hlangu.

The chief was speaking at a meeting in a homestead in Ngqeleni village, where a 14-year-old initiate had died from dehydration after weeks at an initiation camp.

Nosibulele Sqwinta, 38, is still mourning the death of her son, Lihle.

"I don't even know who performed the procedure. When I ask around, no-one wants to talk to me," she says.

"It is very painful and frustrating for me."

Rural South Africa remains patriarchal to a large degree.

Tradition dictates that women should not speak about circumcision.

Ms Sgwinta says she is worried that her other sons may fall prey to an illegal surgeon, as is suspected with Lihle.

The government has tried to wrestle control of the practice from traditional society but that has largely been unsuccessful.

Although traditional surgeons are now required by law to be registered with the authorities, many still manage to operate without permits.

Health institutions now also perform circumcisions as an alternative to the traditional route but cultural purists see this as westernisation of their custom.

Desperate communities have called for traditional circumcision to be banned but the government says that would be a constitutional violation against cultural practices.

Eastern Cape government Traditional Affairs Minister Mlibo Qoboshiyane said the government did not want to interfere in traditional affairs, but it wanted to work closely with communities to tackle botched circumcisions.

"It is only when we speak openly about how the practice is being exploited that we can hope to prevent these deaths," he said.

- Published9 July 2024

- Published29 October 2010

- Published18 June 2010