Economics drives support for Catalan independence

- Published

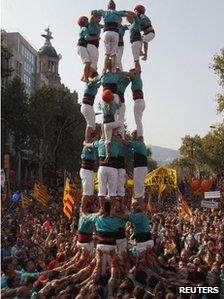

Catalonia's annual independence rally in Barcelona on Tuesday aimed to be the biggest yet

Let's start with the non-financial figures: Catalonia's population is approximately 7.5 million.

The organisers of Tuesday's demonstration say there were two million people demonstrating on the streets of the Catalan capital Barcelona.

The Catalan police, known as Mossos, say there were 1.5 million.

And the Spanish Civil Guard and national police force have come up with a more conservative figure of 600,000.

If we put the propaganda war over attendance aside, any of the estimations constitute a sizeable part of the Catalan population.

However, none of the figures above makes the result of a hypothetical referendum easy to predict.

'Blackmail'

Most past opinion polls suggest a majority would not vote "yes" for independence.

However the political and, perhaps more importantly, economic climate in Spain and Catalonia, has changed.

Political momentum for independence has strengthened

Spain's economic crisis, which is being acutely felt in Catalonia, has galvanised those who campaign for independence from Madrid.

As Catalonia celebrated its national day on 11 September, known as La Diada, Catalan President Artur Mas told me that "if there is not an economic agreement, the road to freedom is open".

Essentially he was blackmailing Spanish Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy: If you (the Spanish government) do not give us a more favourable economic deal, we (the Catalan government) will push for independence for Catalonia.

The political coalition which Mr Mas leads, Convergencia i Unio, is a centre-right nationalist coalition, but in theory it is not pro-independence.

That seems to be changing.

The deal that the Catalan president was referring to is known in Spain as the "fiscal pact".

Catalonia says it pays 15bn euros (£12bn; $19bn) more every year to Madrid than it gets back in funding for services and public projects.

'Bigger slice of pie'

Most economists accept that figure.

So when, last month, Catalonia (the most indebted region in Spain) said it would need 5bn euros from the central government's central rescue fund for troubled Spanish regions, Catalan government sources suggested privately that "they were simply asking for their money back".

Madrid, though, is unlikely to buy that argument or possibly even the Catalan demand that any loan from the central government's rescue fund should come with no strings attached.

There is an uncanny parallel between Catalonia's imminent bailout from Madrid, and Madrid's likely second rescue deal from its eurozone partners.

The Spanish and Catalan leaders are due to meet on 20 September, to discuss the fiscal pact.

The Catalan government essentially wants the same deal as the Basque Country. It wants to collect and manage its own taxes. Or, in British slang, "a bigger slice of the pie".

The main stumbling block in the way of a deal is simple: The Spanish government is itself desperately short of money. A problem which is only compounded by Spain's deepening recession.

The calculation Madrid has to make is whether there is room for a bit of give and take.

Is the political fallout from "no deal" too costly? And therefore is agreeing to a better economic arrangement for the Catalans a price worth paying?

Of course the economics and politics are, as always, inextricably linked.

Fragmentation fears

People here draw a lot of inspiration from Scotland's planned referendum on independence.

However, Madrid refuses to even discuss the idea of independence, and Mr Rajoy looks unlikely to follow UK Prime Minister David Cameron's example by accepting a vote.

And then there is the process: apart from a likely referendum, the political path to nationhood, if pursued by the Catalan Government, is relatively unknown.

In Spanish eyes it is simply unconstitutional.

Despite the chants and banners on the streets of Barcelona on Tuesday night, this region, which has its own language and culture and is clearly distinct from much of Spain, is still a long way from becoming Europe's next independent state.

Fears that Spain would disintegrate were important factors in the country's bloody civil war.

And in the years following Spain's transition to democracy, the regional question was carefully managed.

You can also ask yourself what would be the position of influential European leaders, like Angela Merkel on the Catalan question, within the crisis of the eurozone's sovereign debt crisis.

It's unlikely that the German leader would favour a fragmented, and therefore even more economically weak, Spain.

- Published11 September 2012