Kenya: Will radical Islam ruin Mombasa's charms?

- Published

Community leaders on Kenya's coast are warning that Islamic extremism is on the rise. The killing in August of a Muslim cleric was followed by days of deadly riots in the city of Mombasa, from where the BBC's Gabriel Gatehouse reports on a region caught between economic deprivation and religious fundamentalism.

We met Yusuf Mohamed in an obscure back street of Mombasa.

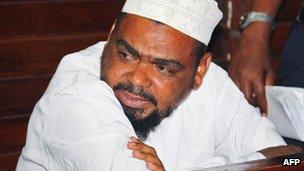

As the mosques filled up for Friday prayers, we discussed the topic the whole neighbourhood was talking about: The recent drive-by assassination of Sheikh Aboud Rogo Mohammed.

The preacher had been driving north of the city.

A vehicle pulled up alongside his car. A gunman - or gunmen - shot him dead at close range.

Mr Rogo's wife was in the car with him. She was injured, but survived.

"They killed him as an animal, not as a human being," Mr Mohamed said.

Nervous

In his 20s, and like many young men in the city of Mombasa, Mr Mohamed is unemployed.

Sometimes he prays at the Masjid Musa, the mosque where Mr Rogo used to preach.

He said people in the neighbourhood were nervous.

Theories that Aboud Rogo was assassinated by the government or the US are fuelling radicalism

"Today it is Mr Aboud Rogo. Tomorrow it might be me," he explained.

People here say it is not the first time "troublesome" Muslims have been targeted.

Aboud Rogo was certainly troublesome.

He urged his followers to take up arms against Kenyan government forces fighting in Somalia.

His name appeared on a US and UN sanctions list, accused of providing "financial, material, logistical or technical support to al-Shabab", the Somali militant group aligned to al-Qaeda.

No-one has admitted to killing the cleric, but many in Mombasa believe he was assassinated at the behest of the Kenyan government.

Some believe the Americans were behind the assassination - allegations both governments have denied - but that belief is fuelling radicalism.

City with two faces

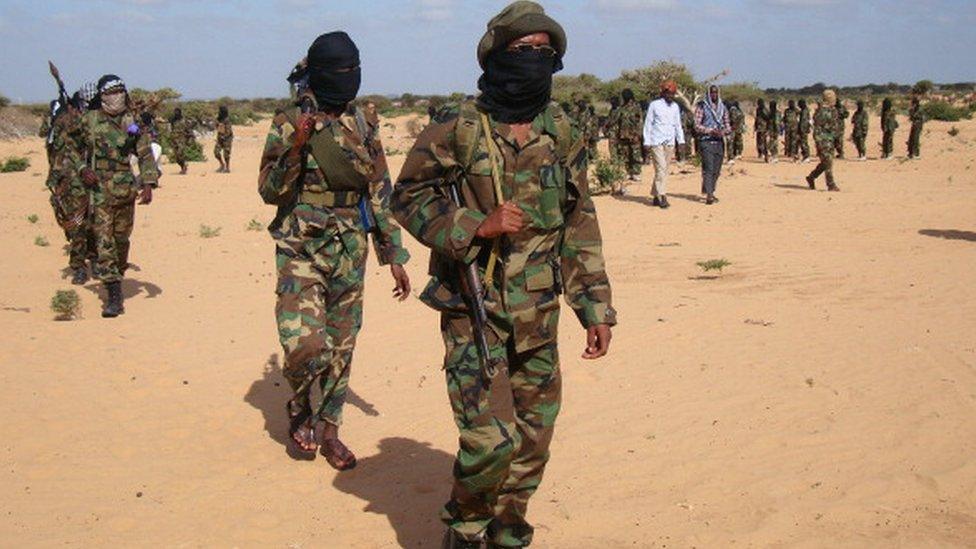

"I think jihad is very slowly gaining more and more credence amongst the youth," says Hussein Khalid, a lawyer at the non-governmental organisation Muslims For Human Rights (Muhuri), based in Mombasa.

"We have seen it happening. We have seen youth leaving their families, leaving their communities and joining militias on their way to Somalia."

Mr Khalid says tensions between the Muslim community and the security services are one reason for the rise in jihadist sentiment.

But he believes there is a deeper underlying cause.

"Look at the youth within the coastal region - there is no employment whatsoever," he says.

"Look at infrastructure - again our region lags behind.

"If you look at the road network in this region - it is amongst the poorest in the country.

Mombasa is a city with two faces.

The killing last month of a Muslim cleric in Mombasa was followed by days of rioting that left four people dead

For hundreds of years this palm-fringed coastal paradise has been a meeting place for civilizations, a place where traders from across the world, both Muslim and Christian, have prospered.

But Mombasa is also a city of entrenched poverty: A place where chronic under investment and high unemployment leave many struggling simply to stay alive.

At the market in the Old Town, stalls are piled high with produce - locally grown fruits and vegetables sit next to imported spices.

But outside, men are picking their way through a vast mound of rubbish.

One squats down, eating long-discarded chunks of food as he seeks out barely edible morsels.

There is widespread support here for a movement known as the MRC, or Mombasa Republican Council, a separatist movement that advocates autonomy for Kenya's coastal region.

Its leaders argue that the coast and its people see little economic benefit from the region's trading ports and tourist industry.

The organisation was banned in 2010, but the order was overturned in court earlier this year.

The MRC draws its support from both the Muslim and the Christian communities.

But recent unrest is threatening to pull people apart.

Beach business

In a mixed neighbourhood known as Kisauni, the Sunday service at the Presbyterian Church of East Africa now features an armed security presence.

Half a dozen officers in camouflage fatigues mingle with the congregation dressed up in their Sunday best.

During the riots, a mob of Muslim youths looted the church and tried to burn it down.

"Actually, they were looking for the pastor," says Beatrice Mburire, one of the worshippers.

"They wanted revenge on another preacher - a Christian preacher," she added referring to the earlier killing of the Muslim cleric.

Outside the city centre, long, white beaches stretch as far as the eye can see. The coastline is dotted with hotels and resorts.

The Ministry of Tourism says the number of people visiting Kenya was up by 3% in the first six months of this year, compared to 2011.

The violence is not helping the tourism industry

But that was before the recent riots, and the modest rise is not reflected on the beaches.

Vendors selling carvings and trinkets say they are much less busy than usual at this time of year.

"Business is very poor now," said Charles Mwandiko, who has been hawking carved elephants and hippos on Mombasa's beaches for a decade.

He blamed al-Shabab and the recent bombing of churches.

It is almost always local people, not tourists, who are the victims of violence on Kenya's coast.

But every time there is a riot or a killing, more and more foreign visitors choose to stay away.

And so the region is caught in a downward economic spiral, with potentially dangerous consequences.

- Published4 July 2023

- Published22 December 2017

- Published2 May 2012