Africa's Titanic: Seeking justice a decade after Joola

- Published

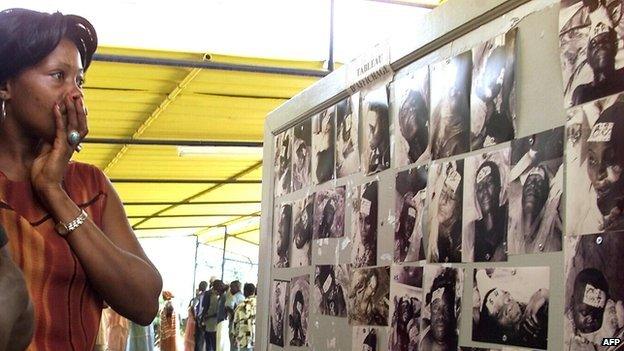

A woman looks at photos of people who died in the Joola ferry disaster

Idrissa Diallo, who lost his three young sons 10 years ago in Senegal's Joola ferry disaster - one of the worst maritime accidents in history - says he will not rest until he finds justice.

The Joola ferry disaster claimed more lives than the sinking of the Titanic in 1912, in which 1,563 people died.

"I am not angry that my sons died, that was God's will. I am angry at the way the aftermath of shipwreck was handled," Mr Diallo says.

He now heads an association for families of the more than 1,800 victims of the accident.

Holding his five-year-old daughter tightly on his lap, he calmly recalls the events of the morning of 26 September 2002.

"I was in the United States visiting family when I received a phone call from Ziguinchor early in the morning telling me the Joola had sunk and that no children had survived.

"My three sons [aged eight, 13 and 15] were on it, they were returning from a visit to their grandmother in Casamance, where my family is from."

The southern province of Casamance is separated from the rest of Senegal by The Gambia, making travel by sea the easiest way of reaching the northern regions and the capital, Dakar.

Only 64 people were rescued from the ferry that day.

Raising the wreckage

About 1,000 of the passengers - many of them children returning to the capital for the start of the new school term - still remain on the Joola.

The Joola ferry remains on the ocean bed off the Gambian coast

The ferry was only built to hold about 580 people - a limit which was routinely ignored, with hundreds of people travelling without tickets.

Though Mr Diallo has no trouble speaking of the events that led up to tragedy, like thousands of other family members of victims, he says he has not been able to properly grieve for his loss.

"How can I say I have grieved when I have not found my children's bodies - when it took me a long time to even believe they were dead? And the government refuses to even talk about it," he says.

One of the main demands of the victims' families is for the ferry to be raised from the ocean floor, so they can claim the remains of their loved ones.

The Joola was not moved after it sank, but Senegal's Environment Minister Haidar El Ali says there was equipment to do so.

At the time of the sinking, Mr El Ali was head of a diving school and part of a rescue team which within days of the disaster would have been able to drag the wreckage to shore.

The rescue mission waited days for the government of the time to give it instructions about what to do with the wreck, but none came, he says.

So the ferry was just left where it was - at a depth of 18m (59 ft) and 20km from the Gambian coast.

The government had a second opportunity to raise the ferry in 2005.

"The European Union granted Senegal the necessary funds to fulfil the operation, but the authorities never allowed it," says Nassardine Aidara, head of the committee for the creation of a memorial for the Joola victims.

No memorial

Mr Diallo says the lessons of the tragedy have not been learned as the authorities have tried to forget it by "abandoning the victims at sea".

The families have also been asking for an official memorial for the victims to be built.

A few days before the presidential election in March, former President Abdoulaye Wade announced he was building one, and even set up a barrier around the space where it was meant to be erected in Dakar, near the sea.

Construction has yet to begin.

A new ferry link linking Dakar to Ziguinchor - the Aline Sittoe Diatta - has been working for four years.

It was a new German boat and there is strict enforcement of passenger numbers.

For Mr Diallo, the only significant change that has occurred in the last decade is the election of a new president.

Macky Sall, who took office in April, has been insisting transparency at the top is a priority, and has ordered audits into most of his predecessor's controversial projects.

Now families of victims are waiting to see whether he will also want to revisit the sensitive issue of the Joola.

Mr Diallo says the association of victims' families met the new prime minister a few days ago, and insisted on the importance of bringing the ship back to the surface and building a memorial.

He also asked for the government not to get in the way of justice when the association files a new complaint against the former authorities.

An inquiry led shortly after the disaster revealed it was down to human negligence.

The ferry, owned by the national navy, was found to be overcrowded and did not comply with international norms.

Mr Wade admitted his government was responsible and the case went to court.

A year later the captain of the ship, who died in the accident, was held solely responsible - an outcome victims' families have never accepted, saying his superiors were also to blame.

"We will find a way to reopen the case, now that the previous government is no longer there to block justice," says Mr Diallo.

The prime minister has promised to examine all of the families' demands.

"I am hopeful that this new government will listen to us," says Mr Diallo.

"I told the prime minister a catastrophe can be useful to a country, if it is recognised for what it is."

- Published9 July 2024