Tunisia’s unemployed revolutionaries head to Europe

- Published

Sofien Dechich, 25, left his home in Tunis, the Tunisian capital, just a few weeks ago with dreams of making his fortune in Italy.

Four days later he boarded a fishing boat which sank 12 nautical miles (22km) from its destination Lampedusa; of the between 100 and 140 on board only 56 survived and Mr Dechich's family do not know if he is alive or dead.

The night he left he called his father and said: "Please ask God to let me go now and survive."

His father told him: "God be with you and take care."

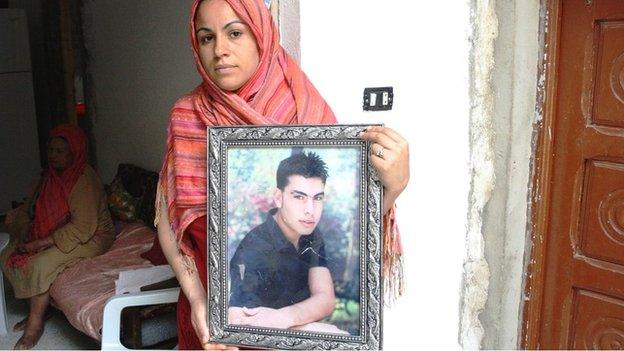

Since the tragedy happened the mothers and sisters of the missing young men have been protesting outside government and embassy buildings in Tunis carrying placards and large, framed photos of their sons and brothers.

Mr Dechich's family was amongst them. His mother is too distressed to speak but his sisters are desperate to get their story heard.

"We want to know what happened. If he is dead we want to see a body. Why are the authorities not telling us everything? We want to know the truth," said Aida Dechich, 31.

In Tunisia locals call such attempts to reach Europe "the burning" - young men, driven by unemployment and poverty, risking their lives to illegally enter Italy in the hope of a better life.

Mr Dechich is from Jebel Ahmar, one of the poorest neighbourhoods in Tunis, a street away from Mutuelle Ville one of the wealthiest suburbs.

It is easy to find "burners" in Jebel Ahmar willing to risk their lives on the dangerous boat trip to Europe.

"I went to Lampedusa and stayed there for a year," says 21-year-old Walid Trabelsi.

"I worked in agriculture and didn't make much money but still life was better," he says.

"Then they arrested me because I didn't have any papers and sent me back. Now I'm unemployed.

"I need to find about 1,000 Tunisian dinars [$640; £395] so I can go again. I'm not afraid. I'm already dead here."

Italian crackdown

Skandar Laabidi reached Italy but was sent back after two weeks

Anis Mathlouthi, 29, is one of the few lucky ones.

Ten years after arriving in Italy he is married to an Italian, he has work and money and all his paperwork is in order.

He is back on holiday and proudly shows off his Italian ID card.

He recognises that "without papers you won't get a good job", but it is these success stories, which continue to drive young men to fill already, overcrowded boats.

Skandar Laabidi, 24, his arm crisscrossed with recent razor blade cuts from self-harming, made the crossing but was sent back after just two weeks and is now thinking of going once more.

"I've been in and out of jail for 10 years and if I stay here I will go to jail again. I'm not afraid about the boat sinking. I'm a good swimmer," he said.

The revolution last year brought a dramatic increase in the number of migrants heading for Italian shores after the Tunisia's security forces reduced their patrols.

The International Organization for Migration (IOM) recorded 27,000 Tunisians arrivals on Lampedusa out of a total of 60,000 - including those fleeing the Libyan war and migrants from other countries.

A crackdown by Italian authorities has meant that this year, many less have successfully made the journey to the island with about 3,300 migrants from all nationalities arriving between January and June.

Yet figures are likely to rise again as many Tunisians have been disappointed by the lack of progress following the revolution.

On the streets of Tunis opinions are mixed about the benefits it has brought.

Bechir Berhouma, 53, a taxi driver, is positive about the change.

"Things are not settled yet but I am optimistic. The transitional government has been good," he said.

"It is just the opposition that have stopped them getting on with their job and the protests which are slowing things down.

"I am also very happy that we have more freedom of speech. Before mouths were shut.

"If you had talked to me about this subject two years ago I wouldn't have shed light upon your question. If you had asked me about politics back then I would have answered about football."

Yet not everyone is so upbeat.

When Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire in December 2010, in an act that ignited youth driven revolution across Tunisia and throughout the Arab world, he was rallying against a system that was not only corrupt and repressive but which offered little prospect of decent jobs for young people like himself.

'Revolution regret'

Ironically, in Tunisia, it is the youth who have perhaps been most disappointed following the ousting of long-time President Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali.

"I regret the revolution and would give up freedom of speech for more jobs," said Linda Landoulsi, 24, studying for a masters degree in linguistics at the Superior Institute of Languages in Tunis.

"When Ben Ali was in power there was a government recruitment scheme for graduates to become teachers [with a monthly salary of 6-800 dinars] but after the revolution it was cancelled," she said.

"Now the only option for a graduate is to work in a call centre earning 400 dinars a month plus commission or teaching in a private school where you earn 300 dinars a month."

Unemployed graduates in Tunis are demanding jobs

A survey by the Tunisian National Institute of Statistics confirms that unemployment has gone up - with 13% out of work in 2010, rising to almost 19% during the revolution and with the figure now standing at 17.6% or 691,700 people.

The price of food has also increased although this is more likely to be a reflection of global trends, rather than the effects of the revolution as many believe.

"A year ago chicken was six dinars a kilo. But now it's gone up to nine," said Sami Chaouachi, 52, a local butcher.

With high unemployment, the rising cost of living, inflation running at 5.5% and strikes, which were forbidden under Mr Ben Ali's rule, disrupting services such as trains - disillusioned youth are turning once more to "burning".

Many of these young men leave from the city of Sfax, which is 275km (170 miles) down the coastline from Tunis it is further away from mainland Italy but closer to Lampedusa - and with less chance of detection by the Tunisian or Italian authorities who patrol the waters.

The sleepy neighbourhood of Sidi Mansour, on the outskirts of the city, where fishing boats gently rock against the shore and local men gather in the shade to chat, offers no hint of its clandestine night operations.

Yet it is soon apparent that people know what is going on.

"They leave here two or three times a month - 100 or 130 people on a fishing boat made for 25," said a local fisherman who wished to remain anonymous.

"During the revolution they were leaving almost every night. Since Ben Ali, left security isn't as tight so now no-one's stopping them."

Ramzi Makni, 30, a public financial administration worker said his brother left five years ago.

"I tried to persuade him not to go. I told him: 'You have a job and a family here.'"

He says that whilst his brother was aware of the risks of making the crossing, he had little idea of what life would be like if he made it.

"He said: 'As soon as my feet land on Italian soil God will take care of the rest.' But it isn't going well. Sometimes we have to send him money. He wants to come back but he's too ashamed because he hasn't made his fortune."

For Mr Dechich's family there is little consolation.

"At night I dream of him. In my dream he's alive and telling us that he's ok," his sister Aida Dechich says.