How much will technology boom change Kenya?

- Published

Farmer Charles Mbatha (left) is now able to check the price of his goods using Susan Oguya's invention (right)

Kenya is seeing a rapid rise in the number of mobile phone apps built by local designers - and both farmers and cash-strapped councils are reaping the benefits.

Susan Oguya spends most of her time tramping through fields in rural Kenya. She is not your typical tech start-up entrepreneur.

Ms Oguya, 25, is the creator of a mobile phone app called M-Farm, designed to help small-scale farmers maximise their potential.

"Me and my two colleagues came up with this app to help our community," she says, as she wanders around a small chilli farm in the Ngong Hills, outside Kenya's capital, Nairobi.

Ms Oguya herself grew up on a farm. She realised people like her parents had two main problems.

Firstly, they did not always know the up-to-date market price for a particular crop.

Unscrupulous middlemen would take advantage of that and persuade farmers to part with their produce at lower prices.

Using M-Farm, a farmer can now find out the latest prices with a single text message.

Collective bargaining

The second problem was that individual farmers would often struggle to sell their produce in small quantities.

So M-Farm allows subsistence farmers to post their produce onto the app, find others growing the same produce, and therefore make it easier to find a buyer. They also benefit from collective bargaining power.

"[We wanted to help] our parents be sustainable in farming and become agri-business rather than subsistence farmers," says Ms Oguya.

Charles Mbatha, the Ngong chilli farmer, seems impressed with Ms Oguya's demonstration.

"This is a new thing for me," he says, as he squints at his mobile. "I am happy that we can sell through phones. Because now I know I can plant something, and I know, at the end of it I will have something [back.]"

Mr Mbatha, like 75% of Kenyans, owns a mobile phone. But mostly these are not smartphones. So M-Farm is a low-tech app, relying on text messaging as its principal means of communication.

In the future, says Ms Oguya, as camera-phones become more widespread, she plans to expand the app to allow farmers to upload photos of their produce, or even send pictures of their crops to experts to get tips on how to be more productive.

In Nairobi, "tech-incubators" are springing up, places designed to give young IT entrepreneurs the space - and sometimes a bit of cash - to develop their ideas.

'Silicon Savannah'

iHub is one such place. It could almost be in Silicon Valley, with young people tapping away at their laptops, or chatting over a café latte at the bar.

But unlike its California counterpart, Kenya's "Silicon Savannah" is focused primarily on local rather than global concerns.

Farmers can now plant crops with a better idea of what money produce will sell for

"In Kenya, everybody is building apps for Kenya," says Eric Hersman, the US founder of the iHub. "They look around themselves and say, 'Well what do most people do?'... 70% of the population is based on agricultural-related businesses.

"And so, what are we doing here? We're solving our own problems. We're solving the problems we see in our own space."

It all began with M-Pesa, a text-based mobile payment system that launched in Kenya in 2007.

M-Pesa has become phenomenally successful.

According to a report by the IMF published in October 2011, M-Pesa "processes more transactions domestically within Kenya than Western Union does globally and provides mobile banking facilities to more than 70% of the country's adult population, external".

Other apps have yet to achieve the same success. But the principle of mobile payment has broad appeal.

Online government

Nairobi City Council recently piloted a scheme to allow motorists to pay parking fees - and fines - on their mobile phones. By eliminating cash payments, the government hopes to reduce corruption and increase its own revenues.

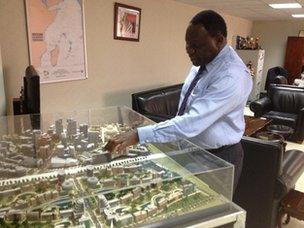

"You remove all these inefficiencies, you improve governance," says Bitange Ndemo, the top civil servant at Kenya's Ministry for Information and Communication.

His grand plan is to put the whole of Kenya's notoriously corrupt government online.

"If we also automated the procurement systems, we would raise another $1bn [£624m]. We would gain far [more] than going out there to look for money from donors."

Mr Ndemo believes that IT has the power to change life in Africa as radically as steam changed life in Europe in the 19th Century.

"[There is] a new industrial revolution that is coming in this digital age," he says.

Civil servant Bitange Ndemo says he wants digital tools to help beat corruption

"We in the third world, we have so much youth. We can leverage on that and be able to leapfrog the economy, instead of going through the same steps that most countries went through."

But Mr Ndemo says his plans for a digital revolution frequently meet with resistance, from Kenyan officials who prefer the status quo, to foreign aid donors wedded to an older system.

But his biggest obstacle may be infrastructure.

Only around 30% of Kenyans currently have access to the internet. For Mr Ndemo's dream to succeed, Kenya will need to move beyond the low-tech mobile app.

"We're at a very early stage in East Africa's technology boom," says Mr Hersman.

But he says he is optimistic about the future. "We don't know quite yet what it will grow up to be.

"But I am very bullish on the ability of the technology sector in Kenya to push this country forward for a long time to come."