Viewpoint: How tribalism stunts African democracy

- Published

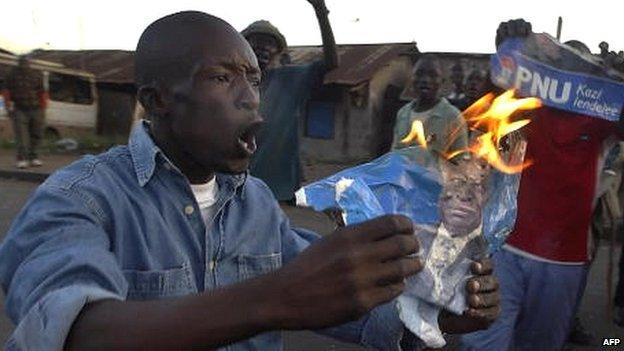

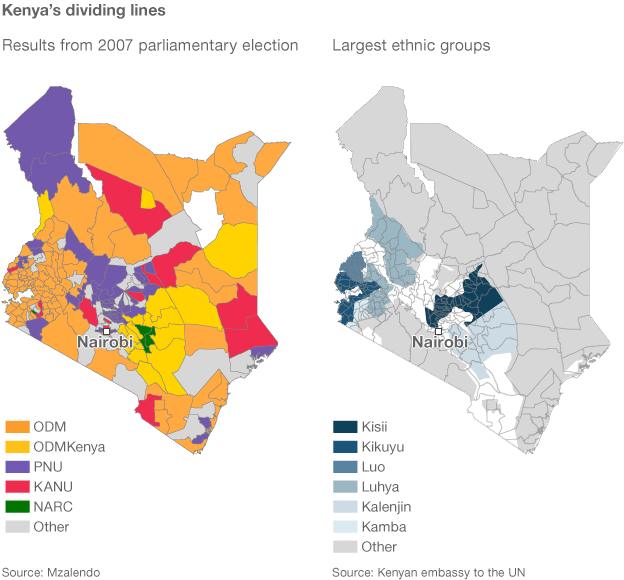

Political violence soon took on an ethnic dimension after Kenya's disputed 2007 elections

Africa's democratic transition is back in the spotlight. The concern is no longer the stranglehold of autocrats, but the hijacking of the democratic process by tribal politics.

Kenya's 2007-08 post-election violence revealed the extent to which tribal forces could quickly bring a country to the brink of civil war.

The challenge to democracy in Africa is not the prevalence of ethnic diversity, but the use of identity politics to promote narrow tribal interests. It is tribalism.

There are those who argue that tribalism is a result of arbitrary post-colonial boundaries that force different communities to live within artificial borders.

This argument suggests that every ethnic community should have its own territory, which reinforces ethnic competition.

The last 20 years of Somalia have shown the dangers of ethnic competition and underscore the importance of building nations around ideas rather than clan identities.

Much attention over the last two decades has been devoted to removing autocrats and promoting multiparty politics.

But in the absence of efforts to build genuine political parties that compete on the basis of ideas, many African countries have reverted to tribal identities as foundations for political competition.

Leaders often exploit tribal loyalty to advance personal gain, parochial interests, patronage, and cronyism.

But tribes are not built on democratic ideas but thrive on zero-sum competition.

As a result, they are inimical to democratic advancement.

In essence, tribal practices are occupying a vacuum created by lack of strong democratic institutions.

Tribal interests have played a major role in armed conflict and civil unrest across the continent.

'Clever and calculating'

But the extent to which it blunts efforts to deepen democracy has received little attention. This is mainly because much of the attention has focused on elections.

According to US-based pro-democracy group Freedom House, 19 African countries, external were considered electoral democracies in 2012, down from 24 over the 2005-08 period.

These trends conceal the influence that tribal politics exerts on the democratic process.

It took Kenyan political parties nearly a decade to unite and defeat Daniel arap Moi's regime.

Leaders of the different opposition parties were primarily focused on pursuing their tribal interests rather than uniting around a common political programme.

They in effect played into the hands of the government in power that could divide them along tribal lines.

The opposition parties were unable to find common ground through coherent party manifestos.

According to research carried out on Kenya by Stephen Keverenge at the US-based Atlantic International University in 2008, external, 56% of 1,500 respondents did not know that their parties had manifestos.

The manifestos are generally issued late because much of the effort goes into building tribal alliances.

The new constitution of Kenya seeks to address the issue of ethnicity by ensuring that a president needs broad geographical support to be elected.

A winner must receive more than half of all the votes cast in the election and least 25% of the votes cast in each of more than half of the country's counties.

But tribal leaders are clever and calculating.

They are quick to dress in the latest fashion and co-opt emerging trends to preserve their identities.

They buy influence and create convenient alliances, shopping for international support in power centres such as London, Paris, and Washington DC.

Their sole mission is self-preservation, with the side effect of subverting democratic evolution.

For them tribal politics is a zero-sum game, so they are prone to using hate speech and inciting violence.

Intellectual input

The way forward for African democracy lies in concerted efforts to build modern political parties founded on development ideas and not tribal bonds.

Such political parties must base their competition for power on development platforms.

The 1994 genocide in Rwanda has led to years of ethnic conflict in DR Congo

Defining party platforms will need to be supported by the search for ideas—not the appeal to tribal coalitions.

Political parties that create genuine development platforms will launch initiatives that reflect popular needs.

Those that rely on manipulating ethnic alliances will bring sectarian animosity into government business.

Whoever is elected as president will spend most of his or her time on tribal balancing rather than on economic management.

Party manifestos are fundamentally documents in which parties outline their principles and goals in a manner that goes beyond popular rhetoric.

They arise from careful discussion, compromise, and efforts to express the core values and commitments of the party.

Building clear party platforms requires effective intellectual input, usually provided through think-tanks and other research institutions.

Most African political parties lack such support and are generally manifestos cobbled together with little consultation.

Tribal groupings see themselves as infallible but parties have to be accountable to the people.

By stating a vision for the future, political parties provide voters with a ways to measure their performance.

Forging platforms fosters debate within parties that transcends tribal and religious differences.

'Road to doom'

Such debates are a central pillar of democracy.

Building modern political parties and associated think-tanks is, therefore, the most urgent way to counter tribal politics.

Policy debate is a key element of democracy.

Specific manifestos would foster healthy political competition that would force parties to distinguish themselves from each other.

Conversely, such debates would also help to illustrates areas of common interest.

Indeed, it is becoming clear that issues such as infrastructure - energy, transportation, irrigation, and telecommunication - and youth employment are emerging as common themes in African politics irrespective of ideological differences.

Botswana is one of Africa's most ethnically homogenous, stable and prosperous countries

The predominance of such issues will select for pragmatic leadership over ideology.

It is therefore not a surprise that African countries are increasingly electing engineers as presidents.

In 2012 six African countries put engineers in top political offices.

This reflects the fact that at the local level, politics is primarily a long footnote on demands for power, transportation, irrigation, and communication.

Closely linked to these foundational concerns are demands for access to education and health.

Political parties are unlikely to differ on essential points, but they might offer different approaches.

So long as democracy offers the best chance for sustained growth and prosperity, tribal politics must be replaced by genuine party platforms and modern democratic institutions like think-tanks.

Otherwise Africa's road to doom will continue to be paved by tribal intentions.

Calestous Juma is professor of the practice of international development at Harvard Kennedy School and co-chairs the African Union's High Level Panel on Science, Technology and Innovation - @calestous on Twitter, external.

- Published17 September 2012

- Published4 April 2011

- Published17 May 2011

- Published19 October 2011