Fighters reveal Rwanda's Congo meddling

- Published

The fall of Goma was an embarrassing moment for the United Nations peacekeepers in the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo.

The largest peacekeeping force in the world, comprising some 17,000 troops, was unable to hold off a relatively small force of mutineers from the Congolese army.

Many at the UN believe the rebel movement, which calls itself M23, has been receiving help from Rwanda.

The Rwandan government denies backing the rebels.

But the BBC has heard evidence that suggests Rwanda's support for the growing rebellion in the eastern DR Congo may be more widespread than previously thought.

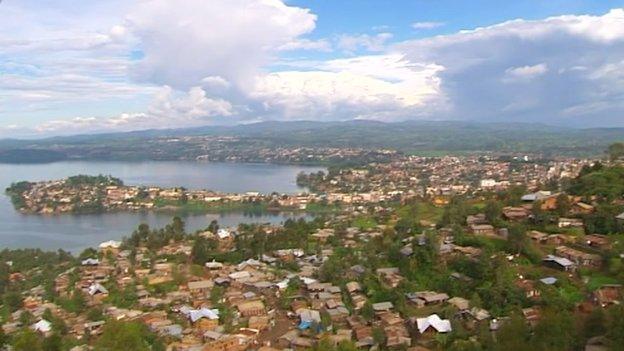

The city of Bukavu lies on the southern tip of Lake Kivu, some 200km (125 miles) to the south of Goma.

There we met two young men, from DR Congo's minority Tutsi ethnic group, who told us about how the rebel movement they had joined had recently been given money by Rwanda.

"We got it [the money] from the Rwanda government," Captain Okra Rudahirwa told us.

"They sent money every month, like $20,000 [£12,500], or sometimes $15,000."

With the money they were able to buy food, uniforms and medicines.

'Instructions'

The two men had both been in the Congolese army at one stage, but had left of their own accord and gone to study in Uganda.

Ex-rebel Bestfriend Ndozi said their orders were to 'demoralise the government'

There in 2010 they had joined the political wing of a group, the Congolese Movement for Change, which was fighting for a better life for the people of eastern DR Congo.

Only in July did they go into the bush with its armed wing to fight the Congolese army.

Capt Rudahirwa and his colleague, Col Bestfriend Ndozi, thought they were part of a home-grown movement.

"Then our chairman came with a delegation from the government of Rwanda, saying that the movement has been changed, that we had to follow the instructions of the Rwanda government," Capt Rudahirwa said.

Col Ndozi said the group, which consisted of around 35 men, was then put in contact with a senior M23 commander, a Col Manzi.

He urged them to co-ordinate with M23 in order to open up a second front against the Congolese army.

"Manzi told us that the Rwandan army had given him the authority to support us and to command us," Col Ndozi said.

"He ordered us to continue our fight, just as M23 were doing in the north, so that together we would demoralise the government."

The men said they decided to abandon the fight once they realised the scale of Rwandan involvement.

Now they say they are in the process of re-integrating into the Congolese army.

The Rwandan government declined to comment on the allegations.

But many of the details of this account, including dates and the names of intermediaries, tally with separate research conducted by the UN.

After the Rwandan genocide in 1994, many of the killers who masterminded the massacre of 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus fled across the border into DR Congo.

Since then, Rwanda has invaded its much larger neighbour on at least two occasions.

The FDLR, as the extremist Hutu militia is now known, is still active, though it no longer represents a serious threat to Rwandan national security.

But less than 20 years since the genocide, that apocalyptic event continues to a large extent to inform the Rwandan government's world view, from its intolerance of dissent at home, to its desire to exert some control over the chaos on its western border.

And so the conflict is spreading.

Rape rising

Instability breeds lawlessness, armed groups operate with near impunity, and civilians bear the brunt.

At a centre for the victims of sexual violence in Bukavu, they told us instances of rape were on the rise.

Eme, not her real name, was assaulted in July.

"I was on my way to the farm," she remembered.

"I saw two young men. One had a gun and was wearing a military uniform," she said.

"He said he had been in the bush without sex for so long.

"Then he raped me. When he had finished he handed me over to his colleague.

"I told them: 'I'm sick', but they just carried on."

Some of the victims at the hospital are as young as six years old.

A woman in her seventies was also recently brought in.

One woman told us: "We are all afraid. Since July, the rapes have started again."

Meanwhile, hundreds of thousands of people have been forced to flee their homes.

This fight, between the rebels and the loyalist army, is essentially a struggle between armed groups.

It is a tussle over territory and access to the lucrative mineral trade.

It is a fight from which very few stand to benefit, aside from the men with the guns themselves and the politicians, Congolese and foreign, who control them.