Nelson Mandela death: Remembering the man

- Published

It has happened: A moment that South Africans have been quietly dreading for years. One of the great lives, and key chapters, of the 20th Century has finally come to an end.

How to measure the significance of a threshold like this - on South Africa or the wider world?

You have to thumb back through many decades of history to find another individual whose life was so intimately bound up in the fate and emotions of a nation.

South Africa's transformation from apartheid to democracy was not the work of one man - a fact that Nelson Mandela himself constantly stressed.

And yet he embodied that journey - in his steely, charming, regal, ruthless, disarming way - and with his death this country seems abruptly cut adrift from its heroic, agonising, brutal, miraculous past - and the long walk to freedom that Mr Mandela lived and personified.

He was an old man, of course. He had planned his slow retreat from public life with the same care and discipline that he had once employed in battling South Africa's racist government.

And so, while there may be shock, there is no great sense of surprise here, and there may be as much thanksgiving as mourning in the coming days.

Some here worry that Mr Mandela was South Africa's "last link" to its heroic past, and that his death will unleash the anger, frustration and resentment that has been simmering here for years - in a country of spiralling inequality and entrenched white economic advantage.

I suspect those fears are exaggerated but the world will be watching this country closely in the weeks ahead.

Discretely, South Africa's establishment - and the myriad factions and institutions that all lay claim to some share of the man himself - have been preparing for this moment for years.

Behind the scenes there will no doubt be tensions between those groups in the coming days.

But as with the 2010 football World Cup, South Africa has a habit of rising to the occasion.

I'll also be doing my best to look back at Mr Mandela's remarkable life and legacy.

But before then, let me share with you some of the comments that I have gathered over the last few years - in preparation for this moment - from Mr Mandela's friends, comrades, relatives and opponents.

Mac Maharaj, fellow Robben Island inmate, now presidential spokesman:

He's a world icon - if you look at the diversity of people who look up to him.

This is a man who is secure in himself - comfortable in his skin.

It's very important that he should not be portrayed as a saint.

The danger is if we make him just as a set of values.

The idea that people in leadership positions are not ordinary humans is a very dangerous concept.

[He was] an ordinary human being.

Other forces, family members, different groups want to make him their property, shaped by their understanding. But in the information age they will fail.

Amina Cachalia, anti-apartheid activist and friend:

The man Mandela is still a bit of an enigma. He has never revealed his very innermost feelings.

I always felt he had built a wall around him.

He's a very ordinary man in many respects and probably has flaws like all of us.

He was most certainly a ladies' man. He liked the company of women.

But he was never a violent man.

He could be very easy going with a very dry sense of humour.

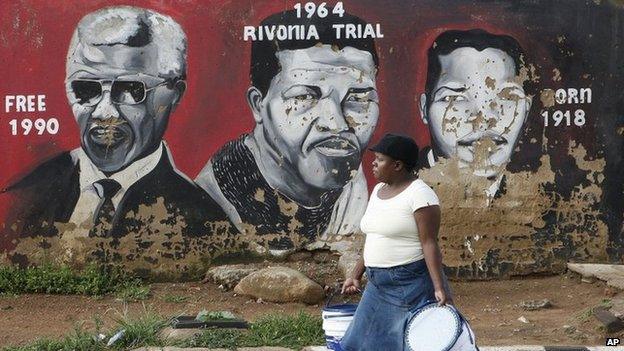

Dennis Goldberg, member of ANC armed wing, fellow defendant at the Rivonia trial:

We expected to be hanged. We really did.

But the majority of the population thought of us as heroes.

Eight of 10 defendants at the Rivonia trial were sentenced to prison terms

Nelson Mandela wasn't just a political leader.

When political activity had become impossible… he found a way forward through armed struggle as political propaganda - to show the oppressed could fight back.

He wasn't just a theoretician.

It's a readiness to do what you're asking others to do that makes for great leadership.

He sums that up at the end of his autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom, when he says, after finally being released, that people said: "You're free,' and he said: "No. Now we are free to be free. Because to be free it is not just enough to cast off your chains."

You must so live your life to respect and advance the freedom of others. That's the legacy.

And I wish all my comrades of today and some in the younger generation of leaders would remember that.

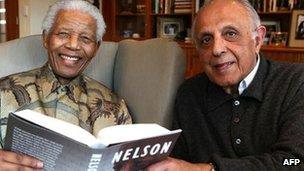

Ahmed Kathrada, fellow Robben Island prisoner:

Much of Nelson Mandela’s book Conversations With Myself was based on chats with Ahmed Kathrada

Anything he undertakes - he is thorough.

When we started playing chess in prison he bought books on chess.

When we had a garden in prison he ordered books on gardening.

When the decision was taken and he initiated the whole move towards armed struggle he saw to it that he could get hold of every book in the world about guerrilla warfare.

Ronnie Kasrils, former member of ANC armed wing:

Nelson Mandela was a grand figure - tall, good looking, upright, a great speaker.

With that elan, charisma, the way he carried himself, he was a tremendous inspirational figure.

He was already something of an underground figure, who put himself outside the law - the so-called "black pimpernel".

He really led from the front in that respect.

His contribution has been absolutely outstanding - sheer brilliance in terms of the way he could play the enemy from within prison and begin to engage and understand… and change the whole paradigm.

It speaks to a quite outstanding mind and people don't give him enough tribute in terms of intellect.

Although there were others of considerable stature [at the Rivonia trial] his speech there does mark him out above the others.

The idea of an icon, a single icon, throughout history, it does work - perhaps unfortunately.

I would say that movements prosper much better with a real collective.

I can remember lots of debates. I can remember asking why we were singling Nelson Mandela out.

We felt we shouldn't single one out.

But we accepted that it is easier to mobilise and captivate public opinion abroad behind one particular figure.

Julius Malema, former president of the ANC's Youth League:

You know nothing about Mandela. You know a man you've seen on TV.

Nelson Mandela spoke about taking up arms and fighting the apartheid regime at a time when it was not the policy of the ANC.

The ANC was an organisation of gentlemen which used to demand freedom by writing letters to the Queen.

We are just continuing with [Mandela's] legacy of bringing life and vibrancy to the life of the ANC.

Carel Boshoff IV, mayor of whites-only Afrikaner enclave of Orania:

The rainbow nation was an optical illusion - as a rainbow also is: A nice concept but far from reality.

It's a pity that Mandela's personal touch could not become the touch of South Africa.

[His influence] will be short lived - too good to be true.

He might be the only uniting symbol that we had in the end.

People saw in Mandela what they wanted to see and believed what they wanted to believe.

He gave them a sense of security that proved in the end to be false.

Jonathan Shapiro, editorial cartoonist known as "Zapiro":

As a cartoonist it's kind of strange being so in awe of someone because we're not praise-singers by nature.

He really has that unbelievable charisma, that effect on people - I felt it.

It was wonderful just watching and listening.

There are a few people who you can criticise and still be in awe of.

You can criticise and still admire their principles, their integrity.

He's one of them.

There's no way you could be a person like Nelson Mandela or Mahatma Gandhi, or Martin Luther King, and not have an enduring legacy.

He is up there with the very greatest people we can think of, and I think for me he embodied the struggle and he then embodied the new democracy and he still embodies the best values that we have had in this country and can have.

Allister Sparks, veteran journalist and friend:

The tragedy is that he wasn't released earlier.

We should have had more of him - more of his wisdom, his power of reconciling a divided country.

Mandela brought a peace-making quality - that was his role.

He had a gift for personal intimacy.

No-one was too small to be of real interest to him.

If there is going to be any recrimination after [his death] it will be from poor black folk who haven't benefited who say he bent over backwards to conciliate white South Africans.

But it was absolutely necessary.

[On the murder of ANC hero Chris Hani in 1993] Mandela was already an iconic figure but he became the leader of the country that night - he realised it was a critical moment.

He knew he had to rise to the occasion… and what he said calmed the country.

He saved the country [from civil war]. No doubt about it.

That's where the natural power of leadership rose up. And the whole country recognised it.

Sarel Roets, ex-military intelligence officer. Witnessed ANC armed wing's bomb attack in Pretoria in 1983:

I think they [the ANC's armed wing] were terrorists. I still believe that 100%.

Most who died were… poor and black.

It wasn't their fighting that solved the problem - we could have got together much earlier if it wasn't for the [ANC's] armed struggle.

Nelson Mandela was involved in preparing bombs to kill people.

I know he's an idol in the world and since he was released from prison he's done a great job.

But that time when he went to jail he was involved in a terrorist organisation.

This is my country. Hate will bring us nowhere… But what's unfair to me is that the victor normally writes history and a lot of things they say today and celebrate are definitely not true.

I wouldn't chose [apartheid] as a system today but I don't think the purpose of apartheid was that bad.

Girl student at Healdtown school, where Mr Mandela studied:

Nelson Mandela is always in the back of my mind.

It's like he makes me do things better.

When I do something bad I say: "Would Mandela do this? How would he feel if he saw me do this?"

I'm going to think like Nelson Mandela.

Justin Schaff, schoolboy, 12, who once visited Mr Mandela:

In this country, if he wouldn't have been there I couldn't have done so many things and we couldn't have lived in peace with everybody together and I wouldn't have had so many different friends and different cultures.

I met the person who made such big changes to the country and the world.