The Biafrans who still dream of leaving Nigeria

- Published

People in Enugu gather discreetly to sing the Biafran anthem and raise the flag

In a quiet, dusty and fairly secluded corner of Enugu city, south-eastern Nigeria, a group of men unfurled a homemade flag and then sang.

"Biafra will live forever. Nothing will stop us," was the gist of their anthem in the Igbo language.

They were not exactly belting it out and instead of hoisting the flag up a pole, it was tied to a metal gate. But there is good reason for discretion - in the eyes of the authorities the gathering is illegal.

On 5 November, 100 men and women were arrested as they marched peacefully through the city's streets after raising the Biafran flag.

They were all imprisoned and accused of treason but then released when the charges were dropped. It appears the government is determined to ensure any agitation for secession is not allowed to gather momentum.

Forty-two years after the end of the devastating civil war in which government troops fought and defeated Biafran secessionists, the dream of independence has not completely died.

"No amount of threats or arrests will stop us from pursuing our freedom - self-determination for Biafrans," said Edeson Samuel, national chairman of the Biafran Zionist Movement (BZM).

Igwe Anthony Ojukwu says the Igbo people feared being wiped out

"We were forced into this unholy marriage but we don't have the same culture as the northerners. Our religion and culture are quite different from the northerners," he told the BBC.

The group broke away from the better-known Movement For The Actualisation of the Sovereign State of Biafra (Massob).

The 1967-70 civil war threatened to tear apart the young Nigerian nation. Ethnic tensions were high in the mid 1960s. The military had seized power and economic hardship was biting.

With the perception that they were pushing to dominate all sectors of society - from business to the civil service - and while they were prominent in the military, the Igbo people were attacked.

Thousands were killed, especially during the clashes between northerners, who are mostly Muslim, and Igbos. To save their lives, Igbos fled en masse back "home" to the east.

"People used to meet fuel tanker drivers who allowed them to hide inside the tankers - some survived that way," remembers Igwe Anthony Ojukwu, the traditional ruler of Ogui Nike in Enugu State.

"As we were licking our wounds… it dawned on us that we could not just stay at home as they would come and fight us and that would mean... extinction," he said, adding that this prompted the move to declare Biafra independent.

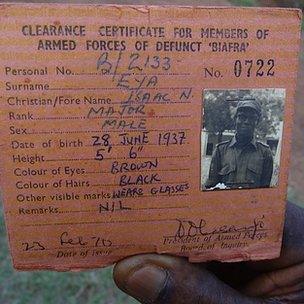

Those who surrendered were issued with cards saying "defunct Biafra"

Today on the streets of Enugu you can hear songs about the war. Booming out from a stall selling CDs and DVDs I heard a song praising the late Chief Emeka Ojukwu - the man who raised the Biafran flag in 1967 and was the leader of the breakaway nation that existed for 31 troubled months.

"It was very terrifying. In the market place you hear a bang and you find limbs flying, people lying dead and others running helter-skelter," said war veteran Chief Nduka Eya, recalling the aerial bombardment by the Nigerian forces.

At his home he showed me the small card he was given after the Biafrans surrendered. It reads: "Clearance certificate for members of armed forces of defunct Biafra."

"Naturally when you lose a war it can be very depressing but what can you do? We took it. But history shows Biafra is defunct out of surrender," said Chief Nduka Eya who is now the secretary general of Ohaneze Ndigbo, an umbrella group representing Igbos around the world.

In the bottom right-hand corner of the card is Olusegun Obasanjo's signature. The man who later became the president of Nigeria played a major role in the civil war, fighting on the federal government side.

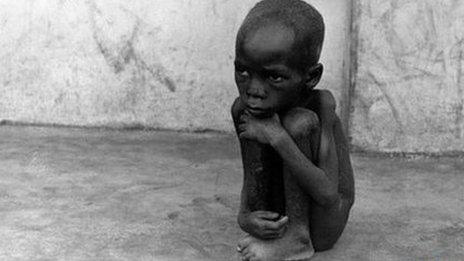

Although no-one knows the true number, more than one million people died in the war - some from the fighting but many more from the resulting famine in the east.

In an effort to repair the bruised nation, the Nigerian head of state General Yakubu Gowan spoke of "No Victor, No Vanquished" and also promoted a policy of Reconciliation, Reconstruction and Rehabilitation.

'Willing to fight'

But to this day, many Igbos complain that they were punished economically after the war and still speak of being marginalised. The fact that no Nigerian president has come from the east is a source of much rancour.

The prospect of an independent Igboland now seems impossible, especially as secessionists would want the area's lucrative oil fields.

While those publicly clamouring for independence are a very small minority, it is not hard to find young people who feel they would be better off as a separate nation. This ought to be of great concern to the government of Nigeria.

"If this present government does not have the solution for us upcoming youth here, I'd rather the nation breaks," said one young man playing football in Enugu near a statue referred to as "The Unknown Soldier" holding a gun aloft.

"We are willing to fight for our rights. Without sacrifice there will be nothing like freedom. We have to pay the price if we want independence and we are ready to do that again," he added.

"Islams (sic) don't want the east to rule the country and our opportunities and rights are denied so we are better off as an independent Biafra sovereign nation. Nothing is impossible," another man in his 20s added.

The renowned Nigerian author Chinua Achebe recently released his memoirs of the war entitled "There Was a Country." The book includes an insight into what life was like for his family fleeing the city of Lagos and heading east.

His account has angered some - especially non-Igbos - and has caused a stir in the Nigerian media as well as on the internet where there are plenty of reminders that ethnic divisions still run deep.

Towards the end of his book Achebe asks: "Why has the war not been discussed, or taught to the young, over 40 years after its end?

"Are we perpetually doomed to repeat the mistakes of the past because we are too stubborn to learn from them?"

Today Nigeria faces massive security challenges - top of the list being the Islamist insurgency in the north that many Nigerians believe is being fuelled by politicians.

Many would argue that some of the root causes of the civil war were also triggers of the rebellion in the north as well as the militancy in the Niger Delta.

"Three words - injustice, inequality and unfair play," says Chief Nduka Eya who, like Achebe, believes it is essential for young Nigerians to learn about the war.

"If you think education is expensive try ignorance," he says.

"Ignorance is a very damaging disease. Our boys and girls need to know what actually happened. 'Why did my father go to war?' Someone in the north will ask: 'Why did we go to fight them?'"

A new beer called "Hero" with a rising sun on the label echoes Biafran nationalist sentiment

Sitting on his throne and holding his ox tail staff of office, Igwe Anthony Ojukwu calls for the war to be studied in schools.

"The experience of Biafra should be shared so that people outside Biafra will know when they are cheated and when they should start to fight for their own destiny," says the traditional ruler.

"The risk of not studying Biafra is that we will continue to subdue the subdueables no matter how justified they are in their demands. We will continue to live a life where the stronger animal kills the other," he says, although he stresses that he is against further efforts to secede.

"I think it is important that Nigeria stays together. Those who are singing for disintegration are doing so for selfish ends."

Forty-two years after the war, a beer has just been launched in eastern Nigeria. The choice of name, "Hero", and the logo on the bottle of a rising sun similar to the one on the Biafran flag were no accident.

These days "Bring me a Hero" is a popular call in the bars of Enugu where people have not entirely given up on the dream of raising a glass to "independence".

- Published5 November 2012

- Published27 September 2012

- Published5 July 2012

- Published2 March 2012

- Published28 July 2023