Longing for peace in Central African Republic

- Published

The ceasefire deal has allowed residents of Bangui, the capital of the Central African Republic under threat from a rebel advance, to breathe a huge sigh of relief.

Though scepticism is also expressed by some let down in the past by agreements not honoured by the various warring factions.

While the deal between the northern rebels and the government of President Francois Bozize was being hammered out in Libreville in nearby Gabon, "fear" was the one word on everyone's lips at Bangui's main market.

It looked like business as usual with fruits and vegetable stalls competing with smoked fish and raw meat, but the market was not crowded.

"People are afraid, there is a real psychosis in the country," Amour Sakine Tokis, the chairman of the market, said.

Everybody was stuck to their radio, wanting to know what was going on in Libreville, he said.

Like many markets on the continent, most of the vendors at Bangui's central market are women.

Marie-Claire Boni, a clothes retailer, said she has been saddened by this new crisis which began last month, one more to add to the long list of coups and periods of unrest in the country since its independence from France in 1960.

"We want peace in Central African Republic," she said.

"We are tired of this. At this time there are even schools that have closed or parents that have sent their children abroad in case there is a war.

"In these conditions, how can we develop our country?" she asked.

One of the tailors at a market in Bangui says the country has stalled since the crisis began: “It is hard to work with this fear.”

The central market has been less busy than usual. Some traders did not come to work, and everyone was watching out for the latest news.

Some of the traders complain about the soaring prices of staple food and common commodities. "Gozo" is crushed cassava used to make a staple typical central African dish. Its price has almost doubled.

“Business is definitely not as good as usual, but we have to get by,” says Pulchery Kowamakoa, a butcher at the market.

The European Union-funded regional force, known as Fomac or Micopax, is posted at Mpoko camp, near Bangui airport, in order to secure the capital. It also has troops deployed in the nearby city of Damara.

A sign in the city centre says: “Central African Republic, country of zo kwe zo”. In Sango, the national language “zo kwe zo” means “everybody is equal”.

In front of the university, some students chatted as they waited for their classes to start. Although some primary schools and high schools have not opened after Christmas break, the university is functioning.

In this neighbourhood called Combattants (Fighters), things have been as busy as usual, although security forces have been more visible.

The popular neighbourhood of PK5 has been as bustling as ever. Many people from neighbouring Chad have settled here. President Francoise Bozize came to power with the assistance of the Chadian army.

Bienvenue Kossi, another shopkeeper, said that over the last month life has been very difficult.

"The road going to Damara, Sibut and Bambari is closed and that is the road where the food comes down," she said.

"So now, the prices are going up and food is harder to find."

The price of "gozo", the crushed cassava used to make a staple dish, has almost doubled since the crisis began.

"The rebels are not Central African citizens," added Ms Kossi.

"They are foreigners. Let them go back to where they came from."

President Bozize has said repeatedly that the Seleka rebels, an alliance of three armed groups, are outsiders interested in the oil resources who have come to destabilise the country.

'Abductions'

The city of Bangui is in the south of country - and is one of the least developed capitals on the continent.

There are no skyscrapers, shopping malls or new buildings here.

All told, the city amounts to a few tarred roads, some banks and public buildings, a few shops and petrol stations, where there are often queues as there are shortages of basic commodities.

Some primary schools have not reopened after Christmas break because of the rebel advance.

But the university has been functioning and in front of the main building students were chatting as they waited for their classes to start.

Bangui has been quiet, but is far from deserted. Shopkeepers, street vendors, and taxi drivers have been going about their businesses.

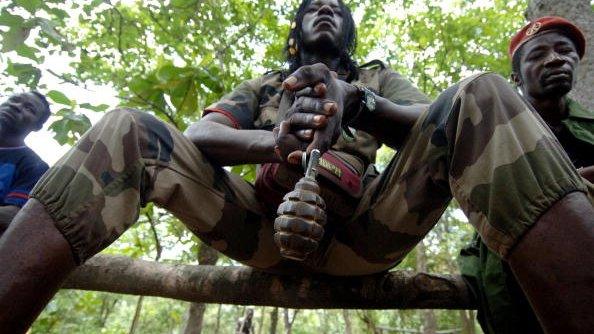

It is the strong military presence in the streets that shows something has been amiss.

In the popular neighbourhood of PK5, the market has been as busy as ever.

In one part of the market where the sound of sewing machines was louder than the noise of traffic, a young tailor explained before the ceasefire announcement how it was hard to work in fear and uncertainty.

A little further on, Germaine Bangue, mother of four, pleaded for France to intervene.

In December, President Bozize asked France and the US come to CAR's aid - a call rejected by both countries.

"Why is France refusing to help us fight the rebels?" she asked.

"They colonised the country, but now they say they don't want to help," she said.

"Meanwhile, we are afraid, and our relatives who are in the north are suffering."

While the rebels have been accused of looting and killing civilians in the towns they have seized, there have also been allegations of abuses on the government side.

"Nowadays, we have been witnessing abductions of people who are supposedly from the same region as some of the leaders of the Seleka coalition," said Marie-Edith Douzima-Lawson, a lawyer and human rights activist.

During the unrest, journalists have also been facing harassment and finding it hard to work, she said.

"I know some who sleep in their radio station because they are afraid to go home and be taken," Ms Douzima-Lawson said.

Some Bangui residents had taken it upon themselves to prevent a rebel infiltration of the city.

A youth group called Cocora - which is very close to the governing party - has been set up to work alongside the security forces and defuse tension in the city.

But some analysts have argued such militias - reputed to be armed and funded by the ruling party - have only intensified the restlessness of the population.

"In Bangui, civilians have been erecting roadblocks after curfew in most neighbourhoods of the city," Ms Douzima-Lawson said.

"They search cars, and the youngsters who are posted there have weapons, machetes."

It is hoped that as the news from Libreville spreads, it will allay the fears that have made it an unhappy new year for many in Bangui.

- Published11 January 2013

- Published22 August 2023