African elephant poaching threatens wildlife future

- Published

The BBC's Gabriel Gatehouse reports on the threat to elephants in Kenya

Three elephant corpses lay piled on top of one another under the scorching Kenyan sun.

In their terror, the elephants must have sought safety in numbers - in vain: a thick trail of blackened blood traced their final moments.

In December, nine elephants were killed outside the Tsavo National Park, in south-eastern Kenya. This month, a family of 12 was gunned down in the same area.

In both cases, the elephants' faces had been hacked off to remove the tusks. The rest was left to the maggots and the flies.

"That is a big number for one single incident," said Samuel Takore of the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS). "We have not had such an incident in recent years, I think dating back to before I joined the service."

Mr Takore joined in the 1980s, and his observations corroborate a wider pattern: across Africa, elephant poaching is now at its highest for 20 years.

During the 1980s, more than half of Africa's elephants are estimated to have been wiped out, mostly by poachers hunting for ivory.

But in January 1990, countries around the world signed up to an international ban on the trade in ivory. Global demand dwindled in the face of a worldwide public awareness campaign.

Elephant populations began to swell again.

But in recent years, those advances have been reversed.

China to blame?

An estimated 25,000 elephants were killed in 2011. The figures for 2012 are still being collated, but they will almost certainly be higher still.

Campaigners are pointing the finger of blame at China.

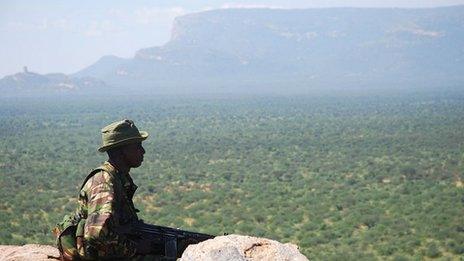

The Northern Rangelands Trust acts like an anti-poaching paramilitary force

"China is the main buyer of ivory in the world," said Dr Esmond Martin, a conservationist and researcher who has spent decades tracking the movement of illegal ivory around the world.

He has recently returned from Nigeria, where he conducted a visual survey of ivory on sale in the city of Lagos. His findings are startling.

Dr Martin and his colleagues counted more than 14,000 items of worked and raw ivory in one location, the Lekki Market in Lagos.

The last survey, conducted at the same market in 2002, counted about 4,000 items, representing a three-fold increase in a decade.

According to the findings of the investigation, which has been shared exclusively with the BBC, Nigeria is at the centre of a booming trade in illegal African ivory.

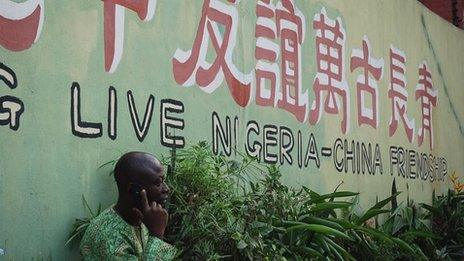

An Asian appetite for ivory, seen here in Hong Kong, has fuelled poaching in Africa

In 2011, the Nigerian government introduced strict legislation to clamp down on the ivory trade, making it illegal to display, advertise, buy or sell ivory.

And yet, says Dr Martin, Lagos has now become the largest retail market for illegal ivory in Africa.

"There's ivory moving all the way from East Africa, from Kenya into Nigera," he said. "Nigerians are exporting tusks to China. Neighbouring countries are exporting a lot of worked ivory items (to Nigeria).

"So it's a major entrepot for everything from tusks coming in, tusks going out, worked ivory going in, worked ivory going out, worked ivory being made."

Paramilitary poacher hunters

The BBC visited the Lekki Market in Lagos. Wearing a hidden camera, a reporter from the BBC's Chinese Service was immediately approached.

Speaking Mandarin Chinese, a Nigerian trader offered "xiang ya" - "ivory". There were piles of carved items for sale, ivory bangles, combs, chopsticks, and strings of beads.

Mr Loldikir says arresting poachers is a waste of time - his men shoot to kill

Another trader proffered two whole tusks, on sale at just over $400 per kilo. When asked how much raw ivory he could provide, he offered to supply 100kg or more.

Increasing prosperity in China, coupled with a large influx of Chinese workers and investors across Africa, has sent demand for ivory soaring.

Kenya runs one of the most effective anti-poaching efforts in Africa.

As well as the KWS (the government-run wildlife protection service) local communities and private conservancies are providing their own armed rangers.

The Northern Rangelands Trust is such an organisation. It runs a "Rapid Response Unit" of about a dozen armed men, who camp out in the thorny scrubland of northern Kenya following herds of elephants and tracking poachers.

The unit is essentially a state-sanctioned paramilitary force. The commander, Jackson Loldikir, and his men wear camouflage fatigues and are armed with Kalashnikov rifles.

Campaigners say Lagos is now the largest ivory retail market in Africa

Theirs is a dangerous job. While out on patrol with the BBC, the group was charged by a herd of nervous elephants.

A ranger had to fire a warning shot in the air to avoid being trampled.

Mr Loldikir says arresting poachers is a waste of time. Prosecutions are rare and the perpetrator is likely to get off with a small fine.

And so Mr Loldikir and his men say they are forced to take more drastic measures.

"When we meet a poacher, we just kill," he said. "It's the only way to protect the animals, just to kill the poacher."

Injuries, even deaths, are not uncommon, on both sides.

"In May, we heard a shot. We met five poachers. They had killed an elephant. So we shot them. We killed one and we recovered two guns. And one of our scouts was also injured."

But the poachers seem undeterred. Conservationists in Kenya are warning that at the current rate, elephants could soon disappear from the wild altogether.

"If the price continues to rise as it is and the killing of elephants continues, within 15 years there will be no free-ranging elephant in northern Kenya, I'm quite sure," said Ian Craig, who runs the Northern Rangeland Trust.

"Wherever there are unprotected elephant and there are firearms, people are going to kill them. They're just worth too much money."

And what applies to Kenya applies also to the rest of Africa.

In a continent where guns are plentiful and poverty is widespread, the rewards of poaching simply outweigh the risks.

- Published12 April 2012

- Published12 December 2012

- Published21 April 2012