Analysis: How serious is Sahara terror threat?

- Published

Following the recent attack on an Algerian gas plant, UK Prime Minister David Cameron says that the Sahara desert has turned into a haven for militant Islamists who are waging a jihad against the West. He says it will take decades to defeat them. What is the background to this growing threat?

The Sahara used to be a thriving economic zone, famed for its long camel caravans laden with salt, which in the Middle Ages was said to be worth more than gold. But times - and trade routes - have changed and now the countries on the desert's southern fringes, mainly ex-French colonies, are among the world's poorest.

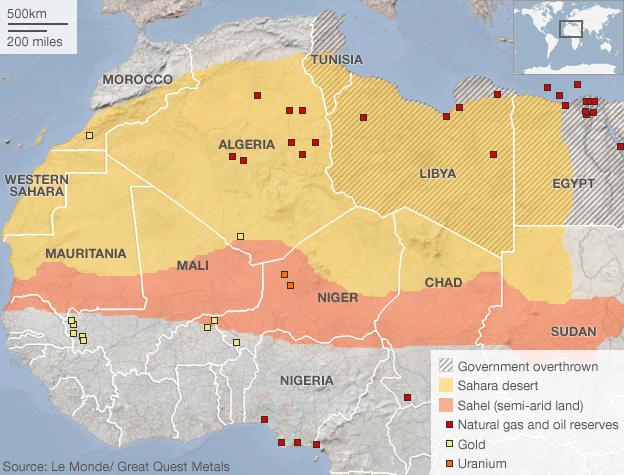

Although most of the desert's inhabitants are poor, there are rich natural resources to be found under the sands. Algeria has oil and gas, Niger has one of the world's largest uranium reserves, which power France's nuclear plants. Mali is Africa's third biggest gold producer.

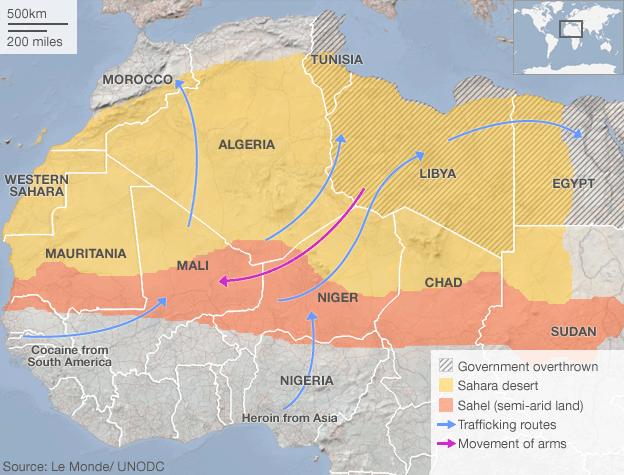

Some of the region's inhabitants have used their desert knowledge for criminal purposes - smuggling migrants and drugs along ancient routes to Europe. Some jihadists have used the profits to buy arms. When Col Gaddafi was toppled in Libya in 2011, many Tuareg fighters returned to Mali and started a rebellion.

The Tuareg rebels joined forces with Islamists who had been expelled from Algeria in the 1990s and had spread across the Sahara, forging links with al-Qaeda and staging attacks in all of the region's countries. In April 2012, the new alliance quickly seized northern Mali - an area larger than France.

Numerous armed groups operate in the Sahara - with a mix of motivations from making money, to self-rule to global jihad. It is hard to know to what extent they work together. There are reports that other militant groups such as Nigeria's Boko Haram and Somalia's al-Shabab have links to the Saharan jihadists.

The militants who attacked the gas facility in Algeria are said to have been from countries across the region. Many Saharans share strong family and cultural ties with residents of the desert in other countries and see the desert as a single vast area rather than parts of several different national territories.

UK Prime Minister David Cameron has said that Islamist extremists in North Africa pose a "large and existential threat" - a comment he made following the siege of a gas facility in Algeria, where dozens of people, nearly all of them foreigners, were killed.

"It will require a response that is about years, even decades, rather than months," Mr Cameron said.

"What we face is an extremist, Islamist, al-Qaeda-linked terrorist group. Just as we had to deal with that in Pakistan and in Afghanistan so the world needs to come together to deal with this threat in north Africa."

The group responsible for the incident in In Amenas in Algeria appears to have been led by Mokhtar Belmokhtar, a local jihadist-criminal who had been a commander of al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM).

He left or was asked to leave AQIM late last year. Branching out, he founded an independent faction called the Signed-in-Blood Battalion that seems to have operated out of territory controlled by the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (Mujao) in northern Mali.

Belmokhtar's faction claims that the assault in Algeria was conducted to avenge the French decision to attack northern Mali.

But, with his organisation reportedly having agents within the compound, it seems likely that this was a longer-term plot that was brought forward in response to the French assault.

It was in fact Belmokhtar's close companion, Omar Ould Hamaha, a leader in Mujao, who declared in response to the French intervention in Mali that France "has opened the gates of hell [and] has fallen into a trap much more dangerous than Iraq, Afghanistan or Somalia".

That Belmokhtar's faction would want to attack a Western target is not entirely surprising.

He has a long form of kidnapping foreigners and AQIM - to which he belonged until last year - has a long and bloody history.

Originally born as the Armed Islamist Group (GIA) in the wake of the military annulling elections that the Islamic Salvation Front was poised to win in Algeria in the early 1990s, the group evolved first into the Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat (GSPC), before adopting the al-Qaeda mantle in 2007 to become AQIM.

The GIA, in particular, has been linked to attacks in the mid-1990s on the Paris metro system, the GSPC to plots in Europe and North America prior to the attacks in New York on 11 September 2001, and the groups across North Africa have historically felt particular enmity towards former regional colonial power France.

American-Syrian Omar Hammami (R) joined al-Shabab in Somalia in 2011

What is worrying about events in Africa, however, is that violent groups espousing similarly extreme rhetoric can be found in a number of countries.

In Mali alone, alongside AQIM, Mujao and the Signed-in-Blood Battalion is Ansar Dine, another splinter from AQIM that has held large parts of the north since last year and has been imposing its version of Islamic law.

In Nigeria, Islamist group Boko Haram has conducted a destabilising and bloody campaign of terrorism in a fight that is rooted in longstanding local social and economic tensions.

Reports emerged last week that a leader from the group may have found his way to northern Mali, while American military commanders have long spoken about the connection between AQIM and Boko Haram.

Further demonstrating the potential links to Nigeria, back in July last year, a pair of men were accused in an Abuja court of being connected to al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), which is al-Qaeda's Yemeni affiliate.

And across the Gulf of Aden from Yemen is Somalia, a country that has been home to al-Shabab, a jihadist group that last year aligned itself officially with al-Qaeda.

There have been reports of Boko Haram fighters training alongside al-Shabab fighters and the Somali group is known to have deep connections with AQAP.

Particularly worrying for Western security planners, many of these groups have attracted an unknown number of foreign fighters.

In al-Shabab, some, like Omar Hammami, the American-Syrian who rose up in the Somali group's ranks before recently falling out of favour, have become minor celebrities in their own right.

AQIM's networks are known to stretch into France, Spain, Italy and even the UK.

Mujao's Omar Ould Hamaha claims to have spent some 40 days towards the end of 2000 in France on a Schengen visa, whilst there have been numerous reports of Westerners being spotted or arrested trying to join the jihadists in northern Mali.

And now in In Amenas it appears a Canadian citizen may have been one of the attackers.

Seen from Western Europe, a dangerous picture emerges, potentially leading back home through fundraising networks and recruits.

But the risk is to overstate the threat and focus on the whole rather than the individual parts.

While links can often be drawn between these groups - and they can maybe be described as "fellow travellers" ideologically - it is not the case that they operate in unison or have similar goals.

Western interests in Africa will be reassessed as potential targets

Often local issues will trump international ones, even if they claim to be operating under the banner of an international organisation such as al-Qaeda.

And looking back historically, it has been a long time since AQIM-linked cells have been able to conduct or plot a major terrorist incident in Europe.

While a number of plots over the past few years have been connected to al-Shabab, so far there is little evidence that they have actually directed people to attack the West.

The bigger threat is to Western interests in Africa - sites such as In Amenas that will now be reassessed as potential targets for groups seeking international attention, or revenge for French-led efforts in Mali or Western efforts to counter groups elsewhere.