The remote mountains of northern Mali - perfect for guerrillas

- Published

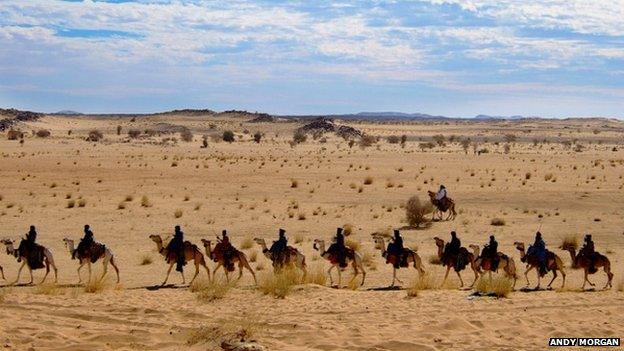

The Tuareg have traditionally led a nomadic lifestyle, roaming across the Sahara Desert

Journalist Andy Morgan describes the remote mountains in the deserts of northern Mali, where Islamist rebels are believed to have fled after French-led forces chased them out of the region's main towns, possibly taking several French hostages with them.

Lost in the middle of Tegharghar mountains in the far north-east of Mali, Esel is a an eerie and magical place.

It is dominated by a vast, smooth boulder, as high as a five-storey building and as long as 10 double-decker buses, that sits on top of a warren of caves.

The rock itself has been split neatly in two by the heat of the Saharan sun and the cold of the Saharan night.

The ground leading to it is strewn with ancient stone arrowheads and axes.

In prehistoric times, those caves were home to hunter-gatherers. Now they could very well be sheltering Islamist militants fleeing the advancing forces of France and its African allies.

I visited Esel a few years ago with Ibrahim, the lead singer of Tinariwen, a group of Tuareg guitarists and poets that I was managing at the time.

For him and for many Tuareg, it is a place of reverence and contemplation, like Ayers Rock in Australia or the Grand Canyon in the US.

It also happens to be on the frontline of Operation Serval, France's continuing mission to rid northern Mali of militant Islamist groups.

The Tegharghar mountains give the word "remote" new meaning.

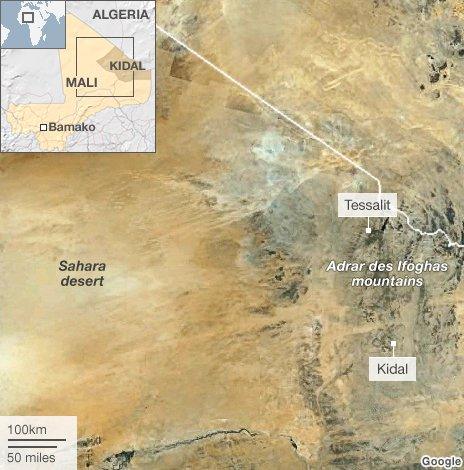

Nearby Kidal, the largest town in a region that is sometimes known as the Adagh des Ifoghas, or The mountains of the Ifoghas tribe, is 1,400 km (900 miles) from the Malian capital, Bamako.

'Impoverished nomads'

It has been at the epicentre of every single Tuareg rebellion against the central government since 1962.

Until the latest rebellion broke out in October 2011, precipitating an exodus of refugees, about 40,000 people lived in the low-slung buildings that sprawl around Kidal's 90-year old French Foreign Legion fort.

The surrounding landscape is desiccated and featureless, encrusted with black rocks that bake under a merciless sun.

It is the perfect place to fake a moon landing.

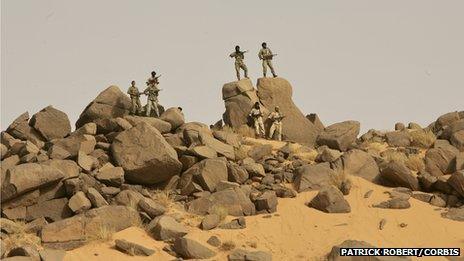

Unfortunately for the French, the Tegharghar mountains are also a perfect place for a guerrilla army.

The annual rains fill up the gueltas, or ponds, with drinking water for nomadic animal herds and insurgents.

The numerous caves offer shelter from sand storms and helicopter gunships.

Impoverished local nomads can easily be persuaded to part with the goats and camels needed to feed a rebel force.

The Algerian border is close and porous enough to keep supplies of food, diesel and ammunition flowing in - as long as corrupt local officials can be bribed or forced to turn a blind eye.

As I write, the French air force is bombing militant positions and arms dumps on the northern edge of the Tegharghar, around the village of Tessalit, a beautiful little oasis located next to a river that floods every June and July, if the rains are good.

Holiday home

France has its eye on the nearby military airbase, a highly strategic facility which it built in the 1950s. It is unclear why its troops have not yet captured the base.

From there, it will be able to fan out and patrol the region from the air.

Any ground convoy of more than three 4X4 vehicles is likely to be targeted, unless it can identify itself in time. The potential for collateral damage is high.

But al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and their allies know the area all too well.

They first set up base here in 2003, using the Tegharghar mountains and the endless desert plains to the north-west as an ideal bolthole in which to hide Western hostages and train new recruits.

Apart from one skirmish in 2009, the Malian army left them to it. Mali has paid the price for that laissez-faire policy.

Tuareg rebels still control the desert town of Kidal

Until 2009, when AQIM made it too dangerous for Westerners to travel north up the vast flat Tilemsi valley, an ancient riverbed which serves as the region's north-south highway, I was planning to build a holiday home in Tessalit.

In the black basaltic hills that surround the village there are endless little valleys that turn green and verdant after the rains.

Some of the hillsides are littered with pre-historic rock art. The all-pervading sense of timeless calm and abundant space is quite intoxicating.

It is a landscape in which you can feel free and it is that freedom that the Tuareg have been fighting for, these past five decades.

The ultimate mission for Mali, France and the international community, beyond Operation Serval and the global war on terror, is to restore some of that magic and peace to the Adagh des Ifoghas.

It will involve not only ridding the region of Islamist gunmen, but finding long-term solutions to northern Mali's political, social and economic problems.

Right now, those problems seem as huge and immovable as the rock at Esel.