Clouds gather over bellwether Tunisia

- Published

- comments

Ennahda supporters come out to rally behind their party in Tunis

"Are you aware of how much pressure there is on you to succeed?" I asked Tunisia's beleaguered Islamist leader, Rachid Ghannouchi, during an interview in Tunis in December.

"Yes," he replied emphatically, with a visible sigh.

He knows all too well the importance of Tunisia succeeding - for Tunisia most of all, but also for a region struggling to forge new relationships between Islamists and more liberal secular forces during a troubled transition from authoritarian rule to democracy.

"A revolution is like an earthquake," explained the soft-spoken head of the Ennahda (Renaissance) Party, who is arguably the most powerful figure in Tunisia's increasingly fractious politics.

"It takes time to form a new landscape."

'Very afraid'

Now Tunisia has been jolted by another powerful political earthquake. The brazen murder last Wednesday of outspoken liberal politician Chokri Belaid, the first political assassination since Tunisia's independence from France in 1965, sent shock waves across Tunisia, and beyond its borders.

"We are very shocked and very afraid," his friend and colleague, Faycal Zemni, of the Modern Left Party told the BBC shortly after his death.

"If Tunisia cannot succeed, who can?" has been the refrain across the region about the small, relatively homogenous North African country.

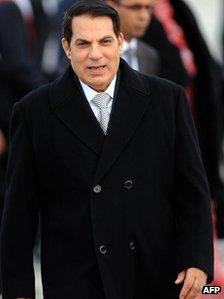

Tunisia was the first in the region to peacefully oust its president

Its comparatively high levels of education, relatively advanced social conditions, including the status of women, and a small, apolitical army, seemed to augur well for Tunisia's historic path.

Tunisia was the first in the region to peacefully oust its president, Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, the first to hold peaceful elections, the first to assemble a ruling troika among Islamists and secular leaders.

Now Tunisia is engulfed by its most impassioned street protests since the heady days of January 2011. And there is a deepening crisis within the ruling coalition over how to respond to this brutal turn of events.

Prime Minister Hamadi Jebali's call for a new government of technocrats has already been rejected by his own Ennahda party, which insists on a political government until new elections.

Ennahda, which had been widely seen as moderate and pragmatic, is now under unprecedented pressure.

Outspoken opposition leaders, including Chokri Belaid, had been accusing the party of giving a "green light" to political assassinations. In what turned into a prophetic news conference the day before his murder, he warned of political violence.

Ennahda officials have reacted angrily to accusations blaming the party for his murder.

In a statement released on Saturday, they said "some rushed to accuse Ennahda Party and its leader Rachid Ghannouchi without any evidence, driven by blind hatred and the avoidance of revealing the real perpetrators".

In recent months, Tunisia's growing political crisis was increasingly visible and, at moments, violent.

On a trip to Tunisia in December, we heard frequent condemnation of the growing role of shadowy "militias". And there were accusations from more secular-minded Tunisians that Ennahda party and the more hardline Salafists were one and the same.

Militias refer to the Leagues for the Protection of the Revolution, neighbourhood watch groups that claim to be rooting out remnants of the old regime. They are accused of thuggery at opposition rallies and trade union marches.

Ennahda officials insist the militias are not their creation, and condemn any violence.

They also insist they have taken action against attacks by Salafists, everywhere from the American embassy to sacred Sufi shrines and art exhibitions deemed to be profane.

Unravelling

In December, Mr Ghannouchi defended his approach, which involved punishing acts of violence that break the law, and reaching out to moderate elements in all political groups.

"Salafists are not one group," he insisted in our interview. "There are those who promote violence and those who denounce it and there are those with whom the government of Ennahda has had confrontations."

He explained how Tunisia's government was the result of "moderate Islamists and moderate secularists" coming together.

But now it's unravelling.

In December, when the Egyptian capital Cairo was engulfed by violent tensions between Islamists and secular forces, many Tunisians we spoke to bristled at suggestions that the crisis in Tunisia was of similar proportions.

"The revolution is not in danger," insisted Mr Ghannouchi then. But he admitted there "was a battle about the new post revolutionary model".

When Faycal Zemni was asked whether he feared more political violence, he seemed to speak for many Tunisians. "When we look at the situation objectively, we risk saying yes, but I prefer to say, 'I hope not.'"

Many will continue to say "watch Tunisia", as a bellwether for the region. But they're watching more nervously now.