Mali prisoner: 'Militants cut off my hand with a knife'

- Published

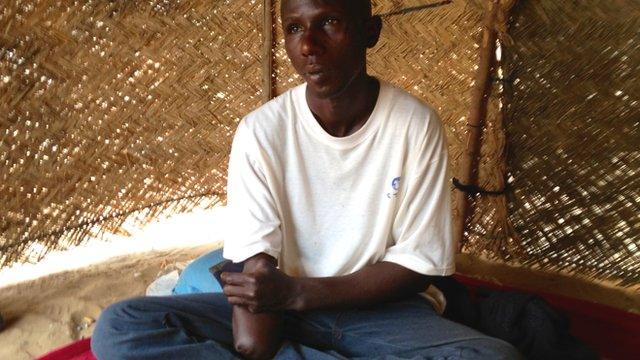

Algalas ag Moutkel points his left arm at the writing on the wall of the cell in which he was incarcerated during the rule of militant Islamists in Gao in northern Mali.

Each day that passed, he would score it with a piece of charcoal. One month, he counted.

When the members of the Mujao Islamist group took him out of prison, he was unconscious at the back of a car being driven to hospital.

His right arm was bleeding as the militants had just cut his hand off with a knife.

"They strapped me against this pillar," recalls Mr Moutkel, a 22-year-old father of three, as we toured the prison where he was held.

He lies against it and bends his knees to show me how he was sat down on a chair.

He then mimics somebody attaching ropes around his legs, his waist and his arms.

"They were many," he says.

"Some of them wore a mask, and one filmed the whole scene with a mobile phone.

"Within a few seconds, one of them emerged from the group with a knife and cut my hand off, just straight like that," Mr Moutkel explains as he moves his stump above his left wrist to imitate the knife.

"I was in hospital when I woke up."

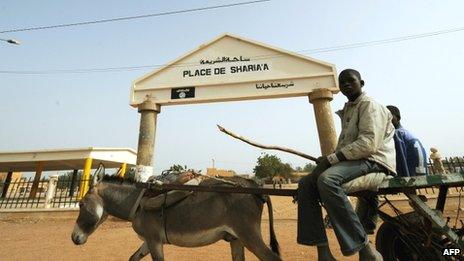

Independence Square was renamed "Sharia Square" by the Mujao Islamists

At least 12 people went through the same horror, either in public or at the back of the prison, according to Gao's mayor Sadou Harouna Diallo.

Five of them had one hand and one leg amputated. Legs were also cut using a knife, reportedly under the knee.

Haunted town

Mr Moutkel was accused of having stolen a mattress.

No evidence was ever brought against him, but the people are too shocked by the brutality and the barbaric act to even discuss the allegation.

A sinister atmosphere still haunts Gao.

Almost every day, the French neutralise mines, grenades or material used for makeshift bombs that were found in houses inhabited by jihadi fighters.

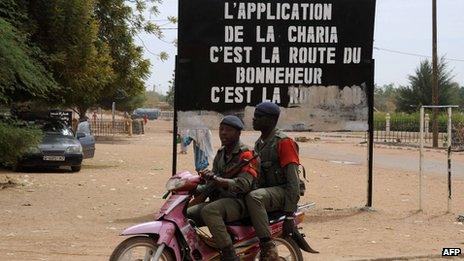

None of the many big black billboards declaring Sharia have been removed. They are planted everywhere.

"Al-hijab for the blessing of Allah and the purity of women," one reads both in French and in Arabic.

It refers to the dress code that was imposed on females.

They had to cover their head, their face and body entirely.

Independence Square was renamed "Sharia Square".

Children now play football in the long dusty pitch where public punishments were carried out.

An employee of the town hall laments that these sign posts are still standing firm everywhere.

Sharia signs can still be seen all over Gao

"We are waiting for the governor to give us the means to take them down," the man says, he refused to give his name.

The Islamists' prison where Mr Moutkel was detained has been emptied but the white Mujao flag drawn onto a black iron sheet is still nailed into the concrete wall above the main entrance.

About 25 prisoners were thrown into Mr Moutkel's cell, which according to my calculation was about 10 sq m (107 sq ft).

'Agitated and scared'

Many of the amputee victims in Gao are now unable to find work

They were not given any food or water.

At times, their Islamist captors would allow member of their family to bring them something to eat.

"The worst was when five persons were amputated at the same time," Dr Abdulaziz Maiga recalls.

"They were very agitated and so scared, we were completely overwhelmed."

The scars left by the harsh Islamist rule are not just visible on Mr Moutkel's stump.

Dr Maiga explains that a rubber tube taken from a bicycle's tyre was usually strapped around the wound by the militants to stop the bleeding while they drove their victims to the hospital.

"We had morphine to calm them down as we had to cut off a few more centimetres in case they were able to get a prosthesis one day," he says.

"The problem is that we did what we could already. Now, these amputees need antibiotics against potential infections, they need regular pain killers.

"But the authorities aren't supporting them at all. Many of them even need psychological help."

Mr Moutkel agreed to take me back to the prison so "people can see for themselves what happened to us here".

"People have to know," he said, complaining that his own government had "abandoned us" during these 10 months of occupation.

Mr Moutkel used to be a worker on construction sites. His amputation means that he cannot work anymore.

"I don't know what I am going to do," he says.

Women were not allowed to dress like this under Mujao's rule

In town, one Sharia sign has been re-painted on both sides with the French flag on one and that of Niger on the other - celebrating the presence of the foreign troops sent to recapture the town.

But the black jihadi paint underneath is still visible.

The French and Nigerien soldiers have beefed up security with the Malian armed forces, but the invisible threat remains.

Some of the most violent militants who swept across northern Mali last year ruled Gao until three weeks ago.

They are now determined to spread terror among the population.

Gao saw the first suicide bomb attacks in Mali's history at the end of last week while on Sunday Islamist militants engaged French-led forces in fierce fighting right in the middle of the town.

"When the French liberated the town, I was so happy that my pain disappeared," Mr Moutkel says in a surprised tone.

"I am serious, it totally disappeared.

"But now, I fear the worst."