South Africa's dreadlock thieves

- Published

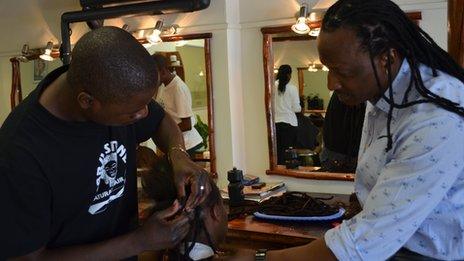

The popularity of dreadlocks has led to the mushrooming of outdoor salons in South Africa

Jack Maseko was recently mugged by three men in South Africa - they wanted nothing but his mobile phone and the dreadlocks he had spent three years patiently cultivating.

"They had a knife and cut off my hair with scissors. I still feel pain when I think about that night," the 28-year-old Zimbabwean tells the BBC.

"I used to see people selling dreadlocks on the streets and didn't know where it came from," he adds, still battling to believe what happened to him as he was walking home late at night in Johannesburg.

Dreadlocks can take several years to grow but many people do not want to wait and it is this need for instant long hair that is pushing the demand for ready locks in the black market, according to hairstylists.

The thieves are quick and sometimes ruthless and will use anything from a knife to broken glass to steal the prized hair - known on the streets as a cut and run.

The gangs operate in Johannesburg but the practice has also spread to the coastal town of Durban, KwaZulu-Natal.

Shoulder-length dreadlocks are sold for between 200 rand ($23; £15) and 700 rand, while longer ones cost as much as 2,000 rand.

So what happens to the stolen hair?

Stylists use a new method known here as crocheting - using a thin needle, they are able to convert relaxed and European hair into dreads by weaving additional human hair pieces into the straight hair - giving a client long-locked hair instantly.

Because this is a fairly new technique, stylists have not built up stockpiles of natural locks, competition is intense and whoever has the locks has the market.

Dreaded thieves

Most South Africans first heard of this phenomenon when the case of another Zimbabwean national Mutsa Madonko, who was attacked and had his hair shaved off outside a Johannesburg night club, made national headlines last month.

Andile Khumalo now covers up his locks when he is walking at night

He had apparently grown his locks for 10 years.

Mr Maseko's former stylist, Andile Khumalo, runs a make-shift salon on the pavement of a busy street in central Johannesburg.

At any given time all three of his salon chairs are occupied, a sign that business is going well, he tells me.

But word of the "hair jackers" is spreading and he is worried that this could affect his business.

"Over the past six months I've heard of four other cases apart from what happened to Jack. This thing is getting worse and something must be done," he says.

Mr Khumalo says he is worried that he might be the next victim.

"I'm even afraid of walking through town with my locks loose especially at night. I make sure I cover my head. It is scary because you never know what they will use to cut your hair - these people are ruthless," says Mr Khumalo.

'Criminal'

The origin of dreadlocks is unknown - they have been most closely associated with Rastafarianism but many African communities have a long history of wearing them.

Some people grow dreadlocks as part of their ethnic identity, cultural or religious beliefs such as Kenya's Maasai warriors who are instantly recognisable by their red-tinted locks.

But for many people around the world, locks are no more than a fashion statement.

South Africa hair guru and businessman Jabu Stone, affectionately known as "Mr Dreads" says this type of hair was not always popular.

"In the mid-90s people would rather burn their scalps with chemicals to straighten it to confirm with the Western standard of beauty than have natural hair and that pained me," he says passionately.

"Locks were perceived [as] unkempt, dirty and only for Rastafarians. It took a lot of hard work over the years to change that perception," says Mr Stone, who has made it his life's work to change the stereotypes about locks.

He has been in this industry for decades and has taken his hair business to the United States and Europe. He says reports of the hair snatchers came as a shock.

"It is not fair because when you grow your locks you get attached to them, you spend years investing in them and for people to just take them from you by force is unacceptable, it's criminal," he says angrily.

"It is a criminal activity and it should come to an end."

No police charge

Mr Stone owns salons in South Africa and abroad and says he does not buy hairpieces if he does not know their origin.

"My policy is simple: If you want to sell hair to me you must produce a photograph of yourself with dreadlocks to prove that they were yours or you come into any of my salons and we cut it off ourselves," he tells me.

He encourages other salons to be as strict - saying that would kill the demand on the black market.

Meanwhile, those who have fallen prey to the hair thieves are not hopeful that their plight will be taken seriously.

"I didn't go to the police because I didn't think they could do anything about it. I just don't believe the police would follow up a case about missing hair," says a distressed Mr Maseko.

The police however are calling for people to open cases of assault.

Jabu Stone (R) is one of the first stylists in South Africa to use the crocheting method to attach hair

"We have only heard stories but no cases have been reported to us," says Johannesburg police spokesman Captain Lungelo Dlamini.

The police say that victims would be assisted in opening a case of assault, but add that there is no suitable charge for the theft of hair.

Other police officials said they believed people were reluctant to come forward out of embarrassment.

Embarrassing or not, many people are fearful of the now notorious hair thieves. For Mr Maseko, just the thought of having locks again is traumatic.

"I'm afraid to have dreadlocks, I'm afraid that they are going to cut them again. My friends have warned me not grow them, next time they might kill me," he says.

- Published1 January 2013

- Published9 July 2024