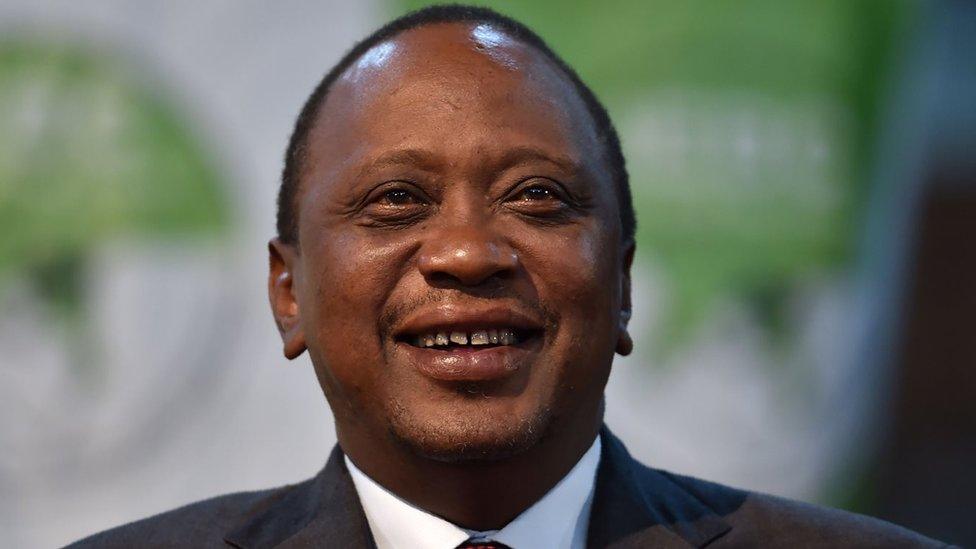

Uhuru Kenyatta: Kenya's 'digital president'

- Published

Uhuru Kenyatta's disputed re-election for a second term as Kenya's president means he will once more have to reunite a divided nation.

His critics question his legitimacy, after his initial victory was quashed by the Supreme Court and the opposition boycotted the re-run.

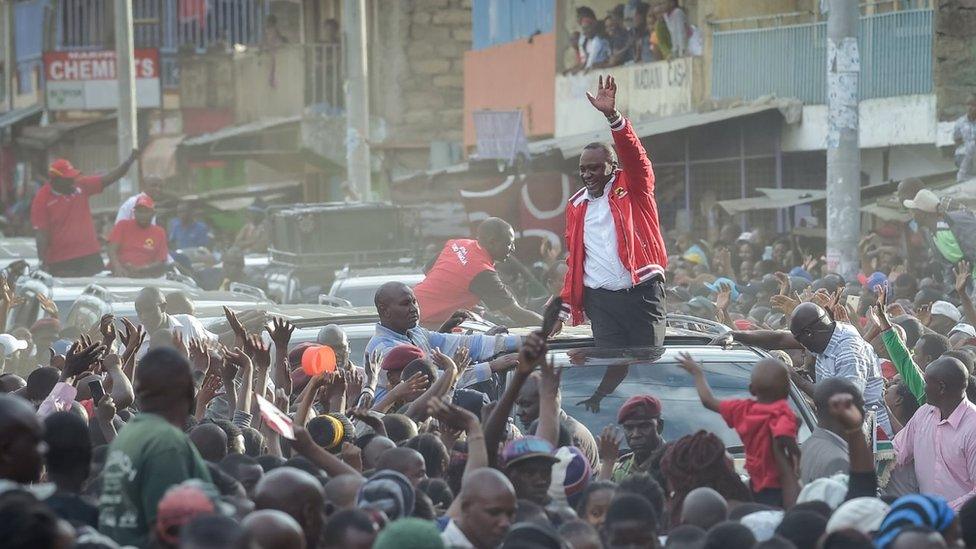

However, his supporters point to a double victory, with a thumping 98% casting their ballot for him the second time round.

At the time of his initial victory four years ago, candidate Kenyatta was facing an indictment by the International Criminal Court (ICC) on charges of crimes against humanity.

The US and British governments had warned Kenyans that it would not be business as usual if Mr Kenyatta and his deputy William Ruto, facing similar charges, were elected.

The Americans warned "choices have consequences" while the British cautioned that relations with Kenya would be scaled back to "minimal contact".

However, Kenya has been anything but a pariah state.

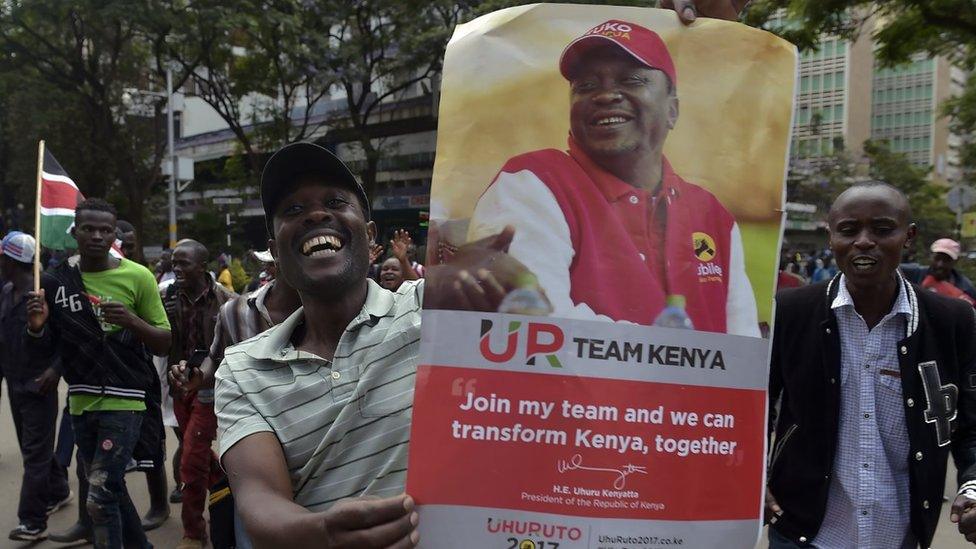

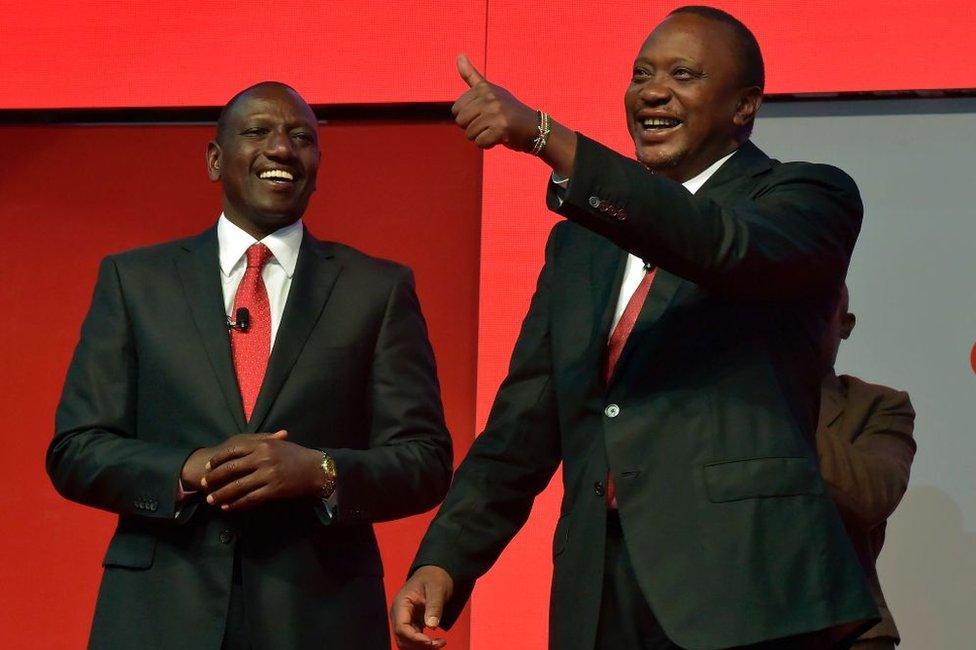

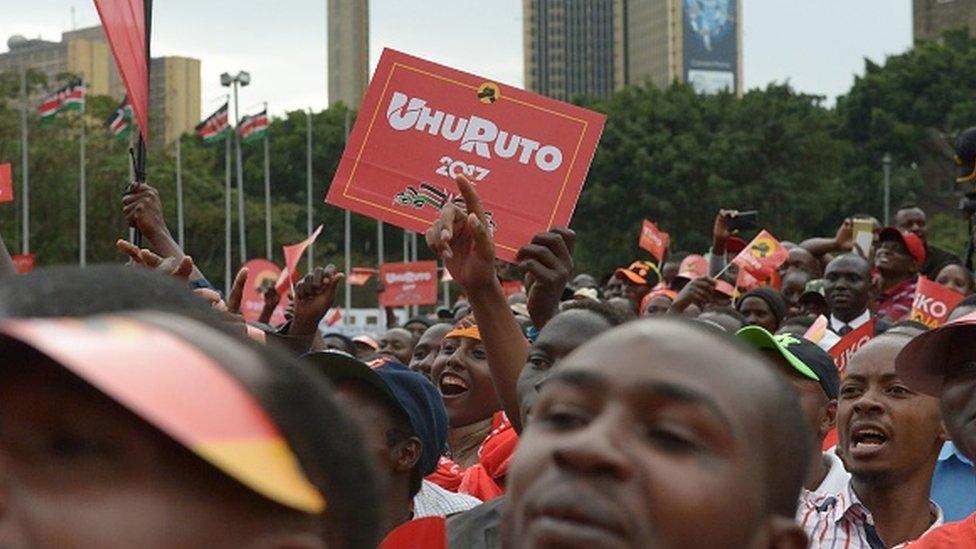

Uhuru Kenyatta's supporters see his recent wins as a double victory for the "digital president"

The East African nation is a key ally for western powers, especially against the al-Shabab Islamist militant group based in neighbouring Somalia, and it didn't take long for its leaders to decide that their strategic economic and security interests were more important than their stance on Mr Kenyatta's presidency.

During his presidency Kenya has hosted several international conferences and world leaders including former US President Barack Obama and Pope Francis came visiting.

In another triumph for Mr Kenyatta's diplomatic skills, he has mobilised many African leaders to put pressure on the ICC to the point of threatening to withdraw from the international court if it did not drop his and Mr Ruto's cases.

Both cases have now been dropped due to a lack of evidence, although the ICC says its prosecution witnesses were intimidated and says the cases could be resumed.

Who is Uhuru Kenyatta?

Born in 1961, became Kenya's youngest president

Brands himself the "digital president"

Accused of organising attacks on supporters of Raila Odinga after 2007 election

Denies charges, denounces them as Western plot

Son of the country's first president, Jomo Kenyatta

Heir to one of the largest fortunes in Kenya, according to Forbes magazine

Digital president

In 2013, Mr Kenyatta crafted a narrative that his main challenger, then and now, Raila Odinga was a project of foreign governments doing the bidding of former colonial powers via the ICC.

He called on Kenyans to reject Mr Odinga and assert their sovereignty. This message resonated with his base mostly from the Kikuyu ethnic group and Mr Ruto's Kalenjin community, leading to the pair's victory.

He also portrayed the older generation of politicians, such as Mr Odinga, now 72, as "analogue" and said they needed to hand over to the young, the "digital generation".

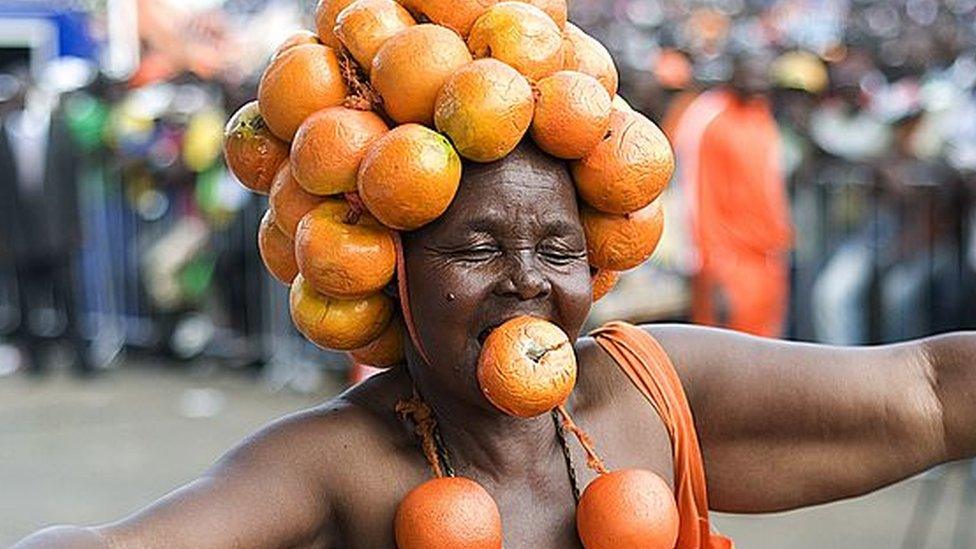

Mr Kenyatta matched his rhetoric with glitz and colour.

Former US President Barack Obama is among leaders who visited Kenya

He was fun, fresh and suave. He was down to earth, approachable and his ardent supporters said he was "demystifying the presidency".

However, while in power, critics have accused Mr Kenyatta of limiting freedom of expression.

His government has passed laws that have been seen as curtailing press freedom.

In 2016, a journalist from the Daily Nation, the country's biggest newspaper, was fired for writing an editorial critical of the president's economic record.

Gaddo, the country's top cartoonist, was also reportedly sacked for drawing a caricature that showed the president tethered to a ball on chain to depict his ICC troubles.

Many were also alarmed when he vowed to "fix" the Supreme Court after it annulled his election victory in August 2017.

Corruption

In many ways, the 2017 vote was a referendum on his record in government - and the verdict was mixed.

Despite the economy growing on average of 5% a year since he took power and foreign investment increasing, many Kenyans still say they are not feeling the effect of the much touted growth.

Kenyatta said the $3.2bn Chinese-funded railway line would improve the economy

An ongoing maize flour shortage and increases in the prices of basic foodstuff have put his government into fire-fighting mode.

His administration has also been accused of excessive borrowing, with an estimate that it has borrowed much more than the accumulative amount borrowed by all past governments since independence. The country's debt currently stands at $26bn (£20bn).

Mr Kenyatta, however, argues that investment in infrastructure like his signature project, the $3.2bn (£2.5bn) Chinese-funded Nairobi-Mombasa railway, will spur growth.

Meanwhile, anti-corruption campaigner John Githongo has said his administration was "the most corrupt in Kenya's history".

In its 2016 report on perceptions of corruption, Transparency International ranked Kenya at 145 out of 176 countries.

It blamed Kenya's ranking on the incompetence and ineffectiveness of anti-corruption agencies, saying that the failure to punish individuals implicated in graft had been a major stumbling block.

Activist say corruption has got worse under President Kenyatta's administration

Mr Kenyatta said his anti-corruption efforts had been undermined by the courts, who were slowing prosecutions and the anti-corruption agency.

In 2015, Mr Kenyatta did act - he suspended and eventually removed five ministers and other high-ranking officials over corruption allegations. Another minister resigned after public pressure.

Political journey

As the son of Kenya's founding father, Jomo Kenyatta, he has always had the name, the wealth and the burden that comes with his heritage.

Growing up, the young Kenyatta always shied away from politics, wanting to be seen as an ordinary person at ease with ordinary Kenyans.

He went to one of the best schools in Nairobi before attending Amherst College in the US where he studied political science and economics.

Mr Kenyatta does not have a natural flair for public speaking but has a powerful voice and can be persuasive when fighting his corner.

He has his mother to thank for ensuring that he mastered the local Kikuyu language, which helps him to connect with his countrymen in rural areas.

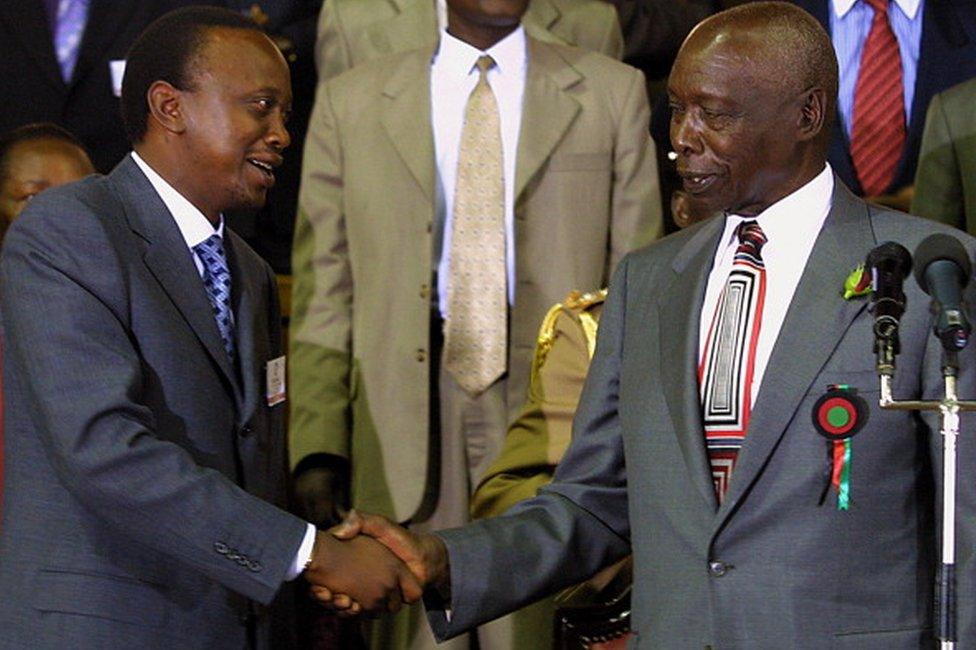

Former President Moi ( right) mentored young Uhuru Kenyatta

They love to call him "Kamwana", which means "young man" - and he made history in 2013 by being sworn in as Kenya's youngest president.

Former President Daniel Moi had named him as his successor in 2001, a decision that led to rebellion in the ruling party Kanu with top members joining other opposition parties to form the National Rainbow Coalition which won the 2002 election.

Mr Kenyatta's claim to be the digital president was a metaphor for his youth but also a political strategy to reach out to Kenya's young population and embrace the country's ambition to become the centre of digital innovation on the continent.

In keeping with his image, he kept his campaign pledge to deliver laptops to primary school children despite some major hiccups.

His administration has also launched e-centres - "one-stop shops" to access and pay for government services electronically in order to cut corruption and bureaucracy.

Supporters point to Mr Kenyatta's successes

Kenyans can now file their taxes and apply for passports, drivers licence, ID cards and access other government services online, cutting hours spent queuing for these services.

His administration also set up an online portal to track government projects and another to report corruption directly to him.

His critics have said that these initiatives are for show and have not helped bring transparency to his government nor helped fight corruption.

Mr Kenyatta boasts very active Facebook and Twitter accounts and has not been shy to join in social media trends.

He once famously did a dab dance.

Media mogul

He is ranked by Forbes Magazine as the 26th richest person in Africa, with an estimated fortune of $500m (£320m).

His family owns TV channel K24, The People newspaper and a number of radio stations, as well as vast interests in the country's tourism, banking, construction, dairy and insurance sectors.

They own huge parcels of land in the Rift Valley, central and coastal regions of Kenya.

Mr Kenyatta projects himself as part of the new generation of Kenyan leaders

It is the land question that haunts Mr Kenyatta and the rest of his family wherever they go in Kenya. In an interview with BBC's HardTalk programme in 2008, he refused to answer how much they owned.

Land is the source of nearly all ethnic clashes that bedevil the Rift Valley. It is so divisive that during the 2013 election the inspector general of police told political candidates not to make it a campaign issue.

Although the 2017 election did not degenerate into nationwide violence, as seen after the 2007 poll, human rights groups say that at least 50 people were killed during opposition protests.

They also warn of a worrying rise in ethnic tension, especially between the president's Kikuyu community and the Luos of his rival, Mr Odinga.

Mr Kenyatta will have to use all his skills of diplomacy if he is to ensure that his second term is judged on his pledge to deliver economic growth, rather than his ability to deal with street protests.

- Published2 August 2017

- Published29 July 2017

- Published22 August 2022

- Published26 June 2017

- Published4 July 2023