Fear stalks South Sudan, the world's newest country

- Published

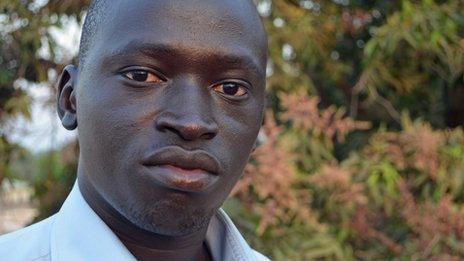

Lawyer Ring Bulebuk Manyiel says he was beaten by soldiers and left for dead

When the world's newest country was born in July 2011 it was not only the South Sudanese that celebrated. The whole world applauded the independence of a people who not long ago had been locked in a two decades long civil war with Sudan to the north.

Democracy, prosperity and freedom of speech were to be the corner stones of this fledgling nation after half a century of combined dominance and neglect by Khartoum.

Yet just 18 months after the joyous street parties that marked its birth, the celebrations seem to be over.

David De Dau, who campaigns for freedom of expression in the capital, Juba, says the optimism of just a short while ago is fading fast amid widespread government repression, continuing violence and abuses of human rights against those who criticise it.

"It was the hope for many people that the guns are going to be silenced. Women and children are no longer going to die, men are no longer going to disappear to be killed in a very crude manner," he said.

"But that has not changed. Instead what is happening is guns are intensifying on a daily basis."

Much of the violence is sparked by long-running and bloody inter-ethnic conflicts.

But some is committed by the nation's own security forces, who are supposed to be protecting the people.

Last December, 11 died after soldiers opened fire on people protesting over the relocation of a local council headquarters in Wau, 400 miles (643km) north-west of Juba. None of those who fired the shots have been arrested.

A third of South Sudan's inmates have not been convicted of any offence

In the same month an outspoken political columnist, Isaiah Abraham, was shot dead at his home by unknown assassins.

Such incidents, insists Mr Dau, are becoming ever more common among those who criticise the government or security services: "Yesterday three people were shot in the head and dumped into the river Nile.

"People keep disappearing but no-one will speak out publicly."

Former journalist, Albino Okeng, who now works for the World Bank and in on the board of a local radio station, watches on with alarm at what is happening.

He used to run an outspoken Southern Sudan newspaper in Khartoum and so knows what it is like to operate under one of the world's most repressive regimes.

Yet life here, he insists, is now little different.

"As far as freedom of expression is concerned I don't think you can separate now South Sudan and Sudan," Mr Okeng said.

"South Sudan is an off-shoot of Sudan and all that is happening here is a copycat of what is happening in the north. And sometimes it is much worse."

Thuggish bush mentality

Family lawyer: They started beating me a lot... thank God I'm still alive

It seems a dreadful irony. The very people that spent decades fighting a civil war that cost an estimated two million lives are now copying the ways of their former enemy.

This practice seems to be extending to his treatment of foreign aid workers.

Khartoum has long restricted how non-governmental organisations (NGOs) operate, what they do and most especially, what they say.

New bills, now going through South Sudan's parliament, aim to do much the same.

Not only that but, as in Sudan, threats to expel NGOs or certain staff members are increasing, along with assaults and arbitrary arrests of their staff.

One aid agency official told me that he and several other NGOs believe the security services are now monitoring their emails and tapping their phones.

In December the South Sudanese army even shot down a UN reconnaissance helicopter.

A teenage boy who was arrested and beaten by the police in the capital, Juba

I put some of the allegations of violence, threats, assaults and arbitrary arrests to a senior government official.

Nodding in assent, he told me that the nation's police force is riddled with officers that have a thuggish bush mentality.

If they believe somebody has abused his freedom of speech they often take matters into their own hands, he added, without consulting their superiors.

When I asked if I could interview him he politely declined saying that if he agreed to that he could lose his job and even his life.

'Afraid to testify'

Junior Minister for Justice, Paulino Wanawilla Unango, was willing to go on the record.

He denied that the failure to find and arrest those responsible for the widespread abuses of human rights here is down to any lack of will by the government.

Instead, he said, it is all down to the unwillingness of victims to testify in court.

"What is happening now is that victims become afraid. They don't want to talk because they fear these people may revisit them and take revenge against them," he said.

"So that is one of the difficulties where victims are not able to come out and tell us who have done what."

Such reticence did not deter young Juba lawyer, Ring Bulebuk Manyiel.

After taking on the case of a woman whose family home was taken from them without warning or compensation by soldiers he was kidnapped and then beaten with electrified rods.

"I asked them why they brought me to that place and they told me that I knew the reason. When I said I didn't they started beating me," he said.

Diplomats fear cutting aid would punish the wrong people

Mr Manyiel's three-day ordeal finally ended after he was dumped in a graveyard and left for dead.

Despite giving police the names of several of those involved no action has yet been taken against them.

With around 97% of seats in the nation's parliament in the hands of the ruling Sudan People's Liberation Movement (SPLM) clamping down on these rogue elements is likely to be difficult in what is essentially a one party state.

Britain's Ambassador to Juba until the beginning of this month, Alastair McPhail, doubts whether withholding UK aid to the country, which currently stands at around £100m ($152m) a year, is an option either.

"It's always a calculation to be made but an awful lot of our programmes are about health, education and food security and if we were to withhold aid then we would be punishing the wrong people," he said.

Local freedom of speech campaigner, Mr Dau, still believes his new nation can overcome its current troubles, but says what started as the fulfilment of a dream is becoming a nightmare for many.

"Now as I talk to you people they go to bed worried whether they will wake up in the morning or not. When morning comes they pray that they passed the night successfully.

"The whole society, the whole community is traumatised. People are living in fear.

"People are losing trust in the government they voted for."