Multiple challenges for Kenya's new leader

- Published

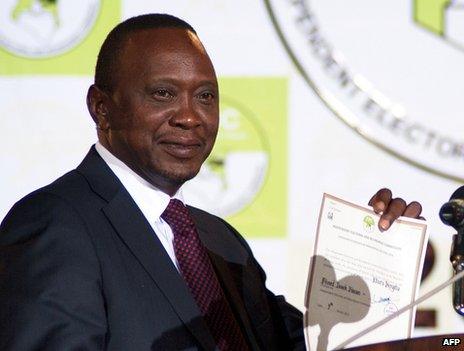

Uhuru Kenyatta is the son of Kenya's first independence leader

"Uhuru [Kenyatta] has won the presidency. It's done. Let's move on." The son of Kenya's first independence leader may not have secured Francis Odera's vote but, like so many other Kenyans, this middle-aged Nairobi resident is just relieved the election has concluded peacefully.

Now he and others believe it is time to return to work and do what Kenyans do best.

Kenya did not burn, in most places riot police remained idle for much of the day, revellers and those licking their wounds showed restraint and Mr Kenyatta and his challenger Raila Odinga drew praise from many Kenyans for statesmanship in their respective speeches.

Yet, as one Kenyan friend put it, there has been a "revolution in Kenyan's political maturity but not a revolution in the leadership".

Kenyans have pinned their hopes on a new constitution, which dilutes the power of the presidency and offers a degree of devolution. Most agree that it was a vital ingredient that helped to avoid a repetition of the violence of five years ago. Kenyans have a right to be proud.

Millions of Kenyans are excited at the prospect of having the youngest leader ever - Mr Kenyatta is just 51. He is a familiar figure, the son of the late Mzee Jomo Kenyatta, but as the country celebrates half a century of independence, Kenya now enters a period of uncertainty .

ICC 'inconvenience'

Mr Odinga is challenging what he calls another "tainted election" tinged with "rampant illegality" at the supreme court.

The detailed allegations will emerge over the coming weeks but it is far from clear whether this "evidence" would significantly sway the result. One has to ask how will Odinga supporters react to a defeat at Kenya's top court?

Meanwhile, Mr Kenyatta and his deputy William Ruto are bound by a fragile ethnic alliance which some commentators doubt will last.

And both men are facing trial at the International Criminal Court (ICC) , externalfor crimes allegedly committed the last time Kenya went to the polls.

Raila Odinga is challenging the result

Mr Kenyatta was delivered a solid mandate by the Kenyan people. The constitutional threshold he crossed to avoid a second round run-off was indeed "paper thin" but he still won outright.

The matter of the ICC is viewed as an inconvenience rather than an impediment by most of his supporters, who regard Mr Kenyatta as an innocent man, confident he will clear his name.

He also now wields tremendous power, influence and personal wealth. The unwritten narrative from the victorious Kenyatta camp is "Game On".

The international community's pre-election threats of "consequences" for Mr Kenyatta may well have backfired.

Their position softened in the days leading up to the election but it was no doubt one reason Kenyans supported Mr Kenyatta's Jubilee coalition.

The Kenyan newspapers bear this out in the post-election flurry, with Ahmednasir Abdullahi, a senior lawyer, writing in The Nation, external that the Kenyatta and Ruto victory "must be seen as a slap in the face of sponsors of ICC cases".

Mr Kenyatta has promised to "honour international obligations" but warned foreigners to "respect the sovereignty" of his country.

Britain, which committed £16m ($24m; 18m euros) to the Kenyan election, is going to have to find an accommodation with the new leadership.

Not only does it rely on co-operation from Kenya to deliver its long-term security agenda but five of the top firms in Kenya are wholly or partly British-owned.

So look out for compromises and a more conciliatory tone. Lawyers are discussing the possibility of giving evidence at The Hague via video link and British businesses will be keen to keep Mr Kenyatta on side.

Price of peace

Which brings us to the issue of peace. Campaigners for justice have coined the phrase "peace coma".

They argue that, blinded by the "haze of peace" which mercifully kept violence off the street, Kenyan voices of dissent risk being hushed for fear of being branded peace traitors.

Jebet, a member of Mr Ruto's Kalenjin community in the Rift Valley, fears that "Kenya has gone back to the Moi era".

President Daniel Arap Moi ruled with an iron fist until the advent of multi-party politics in the early 1990s.

As a Kalenjin, Jebet says: "We have gone back to an irrational system that says, let's take care of our own… and looking after our own has not paid off for the majority of Kenyans."

Jebet, like many other young Kenyans. worries that checks and balances on Kenya's leadership will be muted for the sake of peace.

A prominent commentator from one of Kenya's daily newspapers has spoken of a similar fear: "The peace industry has overwhelmed the media, it has basically become uncritical, losing its oversight role."

These may be premature fears before the president has even been sworn in but they do speak to Kenya's complex contradictions.

On the one hand, Kenya has embarked on a new kind of politics, ushering in a new constitution. The promise of more democratic rights for more people is considered by the majority to have helped deliver a calm and peaceful election.

But it is the same political elite that has secured the levers of power. Many believe the challenge now is for the new leadership to convince Kenyans that they will use that power for the benefit of all, to continue on that democratic path.

A first step would be to reach out to those who did not vote for them.