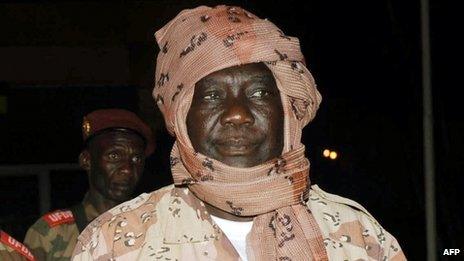

Profile: Central African Republic's Michel Djotodia

- Published

A Soviet-trained civil servant who turned into a rebel commander, Michel Djotodia fulfilled his long-held ambition of becoming leader of Central African Republic (CAR) when he overthrew President Francois Bozize in March 2013.

Often seen wearing a turban, he became CAR's first Muslim ruler, plunging the country into a religious conflict between the Muslim minority and Christian majority.

In January 2014, at a meeting in Chad organised by regional leaders to try to end the violence - which was attended by CAR's entire transitional assembly - Mr Djotodia resigned and headed into exile in Benin.

Although Mr Djotodia had officially disbanded the Seleka rebel group that propelled him to power, its fighters have been involved in a vicious cycle of attacks and counter-attacks with Christian militias, known as anti-balaka.

"While Seleka fighters have notional inclinations for political Islam, they share a strong sense of communal identity and a will to avenge previous CAR regimes and their beneficiaries identified as Christians (not much of a discriminating factor, as the CAR population is more than 75% Christian)," says French researcher Roland Marchal in an article published in September, external.

US anthropologist Louisa Lombard, who was once based in CAR, says Mr Djotodia always pursued his political ambitions "fervently".

"Hearing the stories of his ambition during my research, I almost felt embarrassed on his behalf - he seemed like a Jamaican bobsledder convinced he'd win gold," she wrote when he seized power., external

'Russian hunters'

Born in 1949 in what Ms Lombard describes as CAR's "remote, neglected, and largely Muslim north-east", Mr Djotodia led the Union of Democratic Forces for Unity (UFDR) into a coalition with other rebel groups to form Seleka, which spearheaded the offensive to overthrow Mr Bozize.

For Mr Djotodia, this was sweet revenge: Mr Bozize's rebel forces had toppled his political boss, then-President Ange Felix-Patasse, in 2003.

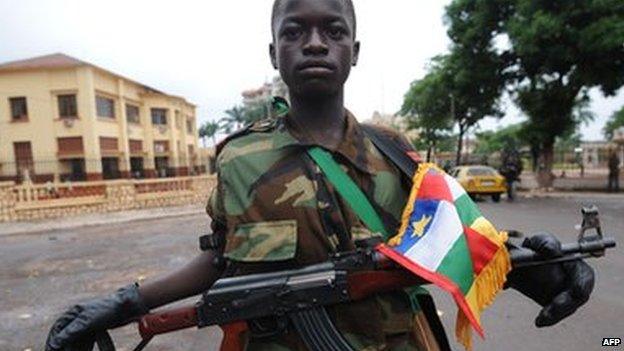

The fighting has forced hundreds of thousands of people to flee

The government says Seleka fighters have been integrated into the army

Mr Djotodia had served in Mr Patasse's government as a civil servant in the ministry of planning after studying economics in the former Soviet Union.

According to Ms Lombard, he ended up staying for 10 years in the USSR, where he married and had two daughters.

He became fluent in several languages, "which made him useful when it came to representing the UFDR to foreigners and the media", she says.

"People in Tiringoulou [village in CAR] tell of one day, long before the rebellion, when a plane of Russian hunters unexpectedly arrived. Upon hearing Djotodia's rendition of their language, [they] declared him not Central African but Russian and brought him along for their tour of the country," Ms Lombard adds.

'Imprisoned'

Mr Djotodia also worked in CAR's foreign ministry and was named consul to Nyala in neighbouring Sudan's Darfur region.

He was said to have used his time there to cultivate alliances with Sudanese militias and Chadian rebels in the area.

"It was these fighters from the Chad/Sudan/CAR borderlands who became the military backbone of the Seleka rebel coalition... The UFDR fighters I knew - tough guys, but a bit ragtag, especially compared to their counterparts in places like Chad or Sudan - could have put up a decent fight against the CAR armed forces on their own, but the 'Chadians' were what made them so unstoppable," Ms Lombard says.

Mr Djotodia was jailed in Benin in November 2006 for using the country as a base for his rebellion against Mr Bozize.

Mr Djotodia (L) was Mr Bozize's (R) defence minister for a short while before ousting him

According to rights group Amnesty International's 2009 report on CAR, external, Mr Djotodia and another rebel leader, Abakar Sabone were, detained without trial in Benin for more than a year, before being released at Mr Bozize's request in the hope that it would the end the conflict raging at the time.

It was probably Mr Bozize's biggest political mistake, as it opened the way for Mr Djotodia to shrewdly play the dual role of peace-maker and rebel leader until he finally seized power in Bangui.