Portugal's unemployed heading to Mozambique 'paradise'

- Published

In 1975, just after Mozambique had won its independence from Portugal after a bitter struggle, a quarter of a million Portuguese settlers fled the country. Fearful for their lives, but also without prospect of a livelihood, the mother country was a safer bet.

Now, nearly 40 years later, the flow is reversing.

With Portugal staggering economically, many now see the country's former colony as holding out more prospects than home.

Businessman Paulo Dias tells a story that is increasingly common.

He moved to Mozambique in 2010 after the financial crisis in Portugal convinced him that his future lay elsewhere.

"I decided to leave because I felt the situation in Europe was catastrophic," says the 42-year-old, who now lives in the capital, Maputo.

In Portugal, Mr Dias ran a company marketing cruise trips. But, after months of struggling, he shut it down.

Within a year he had relocated to Mozambique, where he set up a business building prefabricated houses.

"It was a fresh start and the best decision I ever made," he says.

Henrique Banze, Mozambique's deputy foreign minister, says about 200 tourist and working visas are being granted every day, marking a "huge increase" on recent years.

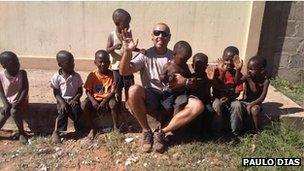

Paulo Dias is now building pre-fab social housing as well as accommodation for large companies

"In the last two years there have been many more Portuguese coming," he says adding: "I suppose it must be to do with the crisis in Portugal."

It is difficult to get firm figures for the influx, but Mr Banze says it is clear that thousands of Portuguese people are relocating each year.

The vast majority - around 20,000, according to some reports - base themselves in Maputo, where the majority of business opportunities exist.

"A tsunami hit Portugal and now everyone is coming here," says Mr Dias. "I don't believe the economic situation in Portugal will improve within the next five years."

Two years ago, when he arrived, most of his countrymen in Mozambique were manual labourers. Now, he says, the middle classes are moving in.

Some, he says, are working for large mining companies with operations in Mozambique. Others, like him, come to set up their own businesses.

Bitter legacy

Mr Dias' new life is not without challenges.

He says the cost of living is high and he struggled during the first year in his new home until he established a partnership with a local businessman who provided the patronage needed to broker deals.

But he has seen his business grow, working on a range of projects from social housing to homes for employees of mining companies.

A few years ago, the thought of moving to one of Africa's poorest countries in search of work would have seemed unthinkable for most Portuguese, particularly given the bitter legacy of the colonial period.

But Mozambique is changing and times are hard in Portugal.

At more than 17%, its jobless rate is among the highest in the eurozone., external

And if there were any doubts of where future opportunities lay, Portugal's Prime Minister Pedro Passos Coelho sent a stark message in 2011.

He told unemployed teachers in Portugal to emigrate,, external urging them to leave their comfort zone and move to Portuguese-speaking countries like Brazil and another former African colony, Angola.

The prime minister may have been talking about teachers, but it was clear that the invitation to leave extended to people in other fields of work.

Thousands are heeding his advice. Several factors, beyond a shared language, have made Mozambique particularly attractive.

Despite Mr Dias' complaints, the cost of living is much lower than in Angola, where the capital - Luanda - was, until recently, the most expensive city in the world.

There is also a perception that Mozambique's growth rate and stable government make it a good place to start a business.

Recent gas discoveries have compounded this sense of optimism.

"With these new discoveries, and with the influx of foreigners here, people will start to spend more and they will want to eat in better restaurants and try different types of food," says Portuguese restaurateur Marcos Silva, who opened an upmarket fish restaurant in Maputo a year ago.

Mr Silva studied interior design in his native country but decided to pursue his passion for food.

Business is now booming. His 160-seat restaurant is often booked out, he says.

In keeping with local laws that cap the number of foreigners working in a company, Mr Silva's partner and manager are both Portuguese, while the rest of the staff - who deal with kitchen and orderly duties - are Mozambicans.

Mr Silva is quick to reject any suggestion that this is an unfair power dynamic.

"It should be seen as an advantage, not as a conquest," he insists. "At the end of the day, it is a niche waiting to be developed. It is a leap of faith we are taking."

Mr Silva's desire to stress this is, perhaps, unsurprising given the Portuguese history in Mozambique.

The former colonial master benefited from slave trading in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Portuguese rule was often heavy handed in the 20th Century. Mozambicans had few rights and were barred from highly skilled and managerial positions until the years immediately preceding independence.

Tense relations and local discontent sparked the military coup which brought independence.

Charles Mangwiro, a Maputo-based journalist at Radio Mozambique, was a baby when Mozambique gained independence. But, since childhood, his parents have told him about the indignities that befell them and fellow Mozambicans under colonial rule.

"They told me there was segregation and the Portuguese were racist.

"My parents say the way the Portuguese spoke to us was insulting and they treated people like they were from a lower class."

Altering attitudes

Turning his attention to the new generations of Portuguese settlers, Mr Mangwiro says local reaction to the influx has changed within a few years.

"At first they were unwelcome because of concerns they would take jobs," he says.

Susana Vidal says local tourism is growing thanks to secluded beaches that are relatively untouched

But that changed after people began getting jobs with the new businesses.

"It's mainly unskilled work - in shops, for example - but it means locals can get money and keep their families running," he says.

Mr Mangwiro says the spike in Portuguese settlers began about four years ago. He says Chinese workers came next, mainly constructing roads and buildings - transforming the capital's skyline. Brazilians and Indians are also coming in droves, he observes.

Although most Portuguese base themselves in Maputo, some - like Susana Vidal - have gone further afield to benefit from Mozambique's growing tourism sector.

The 39-year-old, who has a master's degree in tourism, left her Algarve home for a life in the coastal Mozambique town of Vilanculos four years ago after a three-month job hunt in her native country ended in failure.

Ms Vidal divides her time between her job at a tourist lodge and working with her British boyfriend, who has set up a kite-surfing school.

She says local tourism is growing thanks to secluded beaches that are relatively untouched.

"I go home every year and every time I have to come back after two weeks to my little paradise. It's a good feeling to be here.

"We don't plan to go to Portugal or the UK to start a family. That's a good indication that we feel happy here."

- Published25 October 2024