Nigeria polio: Immunising the vaccine fears

- Published

Two-year-old Abubarkar Al Hassan has the unfortunate tag of being Nigeria's first polio victim of 2013.

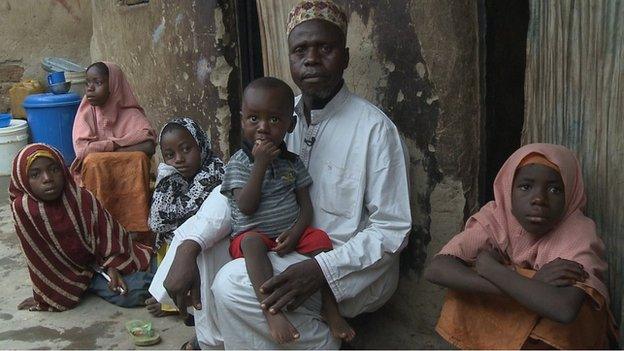

"It's quite upsetting to see that my son cannot play with his friends when they come here," says his father Usman Al Hassan, who lives on the outskirts of Nigeria's capital, Abuja.

"He cannot move unless someone carries him. This makes him cry."

As Mr Al Hassan strokes his son's legs, some of his daughters sit around and one of his two wives prepares a meal in a tiny kitchen off the courtyard.

"I have 14 children and 13 of them are vaccinated; it is very unfortunate that when the vaccinators came around this area they missed my house and my son was not vaccinated," he says, looking at his son who is sitting on his lap.

In the long winding alleys of this community, houses are packed close together.

Open gutters like streams run like central veins carrying household waste water from homes.

Passers-by leap over them to avoid the dirty greyish sludge.

Nigeria has been making some strides in the battle against the polio, which can cause lifelong paralysis, but the task has been slow and fraught with challenges.

The West African nation is only one of three countries where polio is endemic - Afghanistan and Pakistan being the other two.

Journalists arrested

Last year, 122 cases of the virus were reported and the government is hoping to keep the numbers down this year.

"We still continue to miss too many children. In a campaign where you aim to reach 32 million children house-to-house there are number of challenges," says Melissa Corkum spokesperson for the UN children agency's polio campaign in Nigeria.

"In Nigeria there are a lot of nomadic populations on the move… there is no fixed address where you can knock on their door during the campaign," she says.

"This leads to many children being... missed."

Together with the government of Nigeria, Unicef is running nationwide immunisation campaigns.

Polio cases in Nigeria are mostly found in the mainly Muslim north of the country.

In the past few months there have been violent attacks against health workers believed to be connected with polio vaccination drives.

In the most recent attack nine female health workers killed in Kano state.

It is possible that these attacks were the result of religious and political leaders who have opposed the vaccine, saying it is a Western plot to sterilise Nigerian Muslims.

Suspicions about vaccination programmes were fuelled in part by the Pfizer scandal in 1996 when the US drugs firm used an experimental drug during a meningitis outbreak in Kano. Eleven children died and dozens became disabled as a result.

In 2003, these fears and conspiracy theories led to the suspension of vaccination campaigns in Kano, leading to a high number of children contracting the disease.

Then earlier this year, a Muslim cleric and two journalists from Kano were arrested for broadcasting a report saying the vaccines were not safe.

Not all religious leaders are of this school of thought and some regret the harm caused by their colleagues.

"The problem was caused by those who were preaching against it," says Alhaji Attahiru Ahmad, the Emir of Anka in the northern-western state of Zamfara.

'Attitudes changing'

He blames the slow response by the government to the statements.

"They allowed them to have a field day before the intervention, and you know it's difficult to repair damage," the emir said.

Polio cases in Nigeria are mostly found in north of the country

He and other traditional rulers in the area have been trying to counter criticism of the vaccine.

During the last polio campaign in this area, a father refused to have his child immunised.

He was brought to the emir who convinced him to immunise his child.

However the talk of polio remains a very sensitive subject and many in these communities shy away from talking about refusing immunisation.

But the Nigerian government says they are making strides in reducing suspicion among vulnerable communities.

"People are becoming more aware and are realising that in fact the vaccine is safe, it's efficacious, and that other parts of the world have actually used it to eradicate this disease," says Dr Ali Pate, Nigeria's junior minister of health who also heads the presidential campaign against polio.

"This [is a] collective effort. For the first time, you have the entire global community focusing on a single disease, after smallpox, to eradicate."

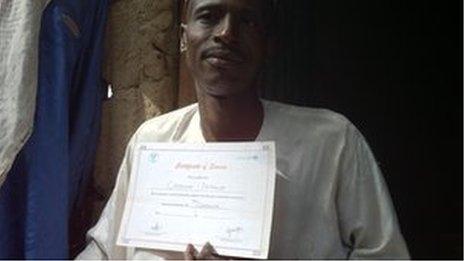

Part of the government campaign has involved community mobilisation workers who talk to people about the benefits of the vaccine.

'No blame'

In the case of Abubarkar, his contracting polio has had a positive effect on his neighbours.

"People are aware, now they know that the disease is real," says Yakubu Yahaya, a social mobilisation officer.

Usman Al Hassan says he hopes his son's case will prompt others to immunise their children

He has in the past had difficulties convincing the people in that community that polio as a disease was a reality.

"They were saying it is either politics or religion or because they want to make their children infertile," he says.

"So they are really now ready to comply with all the vaccinators."

For Abubarkar and his father, the lesson learnt has been a harsh one.

"I do not blame the vaccinators for missing my son, what has happened was God's will," says Mr Al Hassan.

"At least because of him, others can now take this seriously and immunise their children."

Those working on the government's drive against polio, will also be hoping that lessons can be learnt and they can indeed make strides towards eradicating the disease by 2014.

- Published14 January 2013

- Published26 November 2012

- Published18 February 2019