Niger Delta pollution: Fishermen at risk amidst the oil

- Published

Will Ross visits a Nigerian community still making a living from traditional farming and fishing

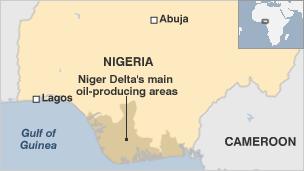

A pristine paradise - these are not words you often hear to describe the Niger Delta in southern Nigeria.

But you get to appreciate the area's natural beauty whilst wading across lily covered creeks and trekking deep into the forest, accompanied by birdsong.

Welcome to the Niger Delta before the oil.

"I'm on the plank now so walk right behind me," a guide said as we squelched across a muddy swamp trying not to sink in too deep.

After walking for about an hour and a half from the village of Kalaba in Bayelsa state, I caught the first glimpse of an expansive tranquil lake through the trees.

On the shore are shelters made of wooden poles draped in material.

Every two years several families set up a camp at Lake Masi where they fish for just three months.

Most people living near the creeks do not benefit from the oil wealth in the region

"After preparing the nylon and woven basket nets we go into the lake and drive the fish into one area," Woloko Inebisa told me.

"By fishing every two years we allow the fish to grow large. If we fished every year there would only be very small fish here," the 78 year old told me as two men in dug out canoes adjusted the nets inside a section of the lake that had been fenced off with cane reeds.

Smoke drifted across the camp as women dried the fish over home made grills above smouldering fires.

"I will use this money to pay my children's school fees, to buy books for them, to buy their school uniforms and to do everything for them," said mother-of-three Ovie Joe.

When these families return to their villages they will continue to grow crops but will have raised some capital from the fishing season.

"We have water for drinking and plenty of fish. But I'm not just here to feed my stomach - I'll save up money for when I go back to the village," Mr Inebisa said.

No birdsong

Just a few kilometres away near Taylor Creek is a very different picture.

An oil spill from June 2012 has left the ground covered in a dark sludge and the trees are all blackened by fire.

Villagers in the Niger Delta rely on fishing season to raise extra capital

Environmentalists believe local contractors often pay youths to set fire to the area where the spill has occurred.

This can reduce the spread of the oil but has other detrimental effects on the environment.

Despite extensive flooding late last year the oil has not dispersed and there are still signs of the rainbow sheen on the surface.

Your ears also tell you all is not well - there is hardly any birdsong as the pollution has sucked the life out of the area.

"When I walked here the crude oil was spilling out so fast I couldn't even get near the spill point itself," said Samuel Oburo, a youth leader from Kalaba.

Running through this area is an underground pipeline belonging to Nigeria AGIP Oil Company - which is partly owned by the Italian oil giant, Eni.

It says numerous leaks near Taylor Creek were all caused by people breaking into the pipe - sabotage.

On 23 March Eni issued a statement announcing the closure of all its activities in the area because the theft of oil, known as bunkering, was so rife.

"The decision was made due to the intensified bunkering, consisting in the sabotage of pipelines and the theft of crude oil, which has recently reached unsustainable levels regarding both personal safety and damage to the environment," the statement read.

People in the village suggest corroded pipes as a possible trigger of the spill and they doubt it was caused by sabotage.

'No prosecutions'

The breaking of pipes and theft of the oil is so rampant in the Niger Delta that experts believe several interest groups are involved.

"There is a high level conspiracy between the security forces, the community and oil workers to steal the oil," says environmental campaigner Erabanabari Kobah.

"That is why people are not prosecuted and convicted even though the crime is happening at an alarming rate," he says.

There is very little transparency when it comes to the awarding of contracts to clean up any oil spills.

Fishermen like Jeti Matikmo have to trek two hours to find clean water before casting their nets

This has led to increased incidents of sabotage as some believe the more oil spills there are the more money there is to share around.

The pollution is having a terrible impact on the environment.

"There is oil here. We are suffering," said Jeti Matikmo, carrying a pole on his shoulder on which bundles of fish were tied.

"Many of our crops are not growing well because of the oil spill and we are not killing fish in the ponds anymore.

"So we have to trek for more than two hours to where it is clean and where there is no oil."

Back at Lake Masi a crowd gathered as two men waded ashore dragging an enormous woven basket behind them. It was heavy with fish.

"There's nothing like pollution here. Although if the oil prospecting companies come they may find oil and all that could change," said Mr Inebisa.

"If this pond is polluted, hunger is the answer," he said adding that in his entire life he had not gained a single coin from the oil of the Niger Delta.