Tunisia's radical divide over Salafi agenda

- Published

Thirty-year-old Tunisian blogger and secular activist Lina Ben Mhenni is concerned about death threats posted on her Facebook page and sent to her mobile phone.

"You see this message is in Arabic, it reads: 'You infidel, we will kill you.'"

Pointing to another message, she says: "And this is just as clear: 'We will find you.'"

Ms Ben Mhenni has won international awards for her campaign in a popular uprising that ousted Tunisia's long-time leader in 2011.

The comments she has received come as a surprise because Tunisia has had a reputation for being one of the most secular states in the Arab world.

Lina Ben Mhenni says she has also been harassed by hardliners on the streets physically and verbally

The women in short dresses and men in designer jeans sitting in bustling cafes that serve beer and wine in Avenue Habib Bourguiba still lend the capital, Tunis, a veneer of Western secularism.

But many of the country's more radical religious groups do not like people like Ms Ben Mhenni pushing to keep post-revolution Tunisia liberal and secular.

"This is not Tunisia it used to be," she laments

"Radical Islamists are flourishing in the new Tunisia. They are a minority but have become very vocal."

Ms Ben Mhenni says those who disagree with her do not limit their criticism to Facebook or texts.

"I have often been harassed by hardliners on the streets physically and verbally."

Online videos

Since the revolution, Islamists of every stripe have emerged after years of oppression under the ousted regime of Zine al-Abidine Ben Ali.

They range from moderates like the ruling Ennahda movement to ultra-conservatives known as Salafists.

No longer the target of state security agencies, they have founded political parties, charities and their leaders have become regulars on television talk shows.

The majority of the Islamists are committed to non-violence, but there is a minority of jihadists who use violence.

There are many authentic online videos showing hardliners calling for the assassination of prominent opposition leaders and taking pride in the desecration of ancient shrines, which they consider un-Islamic, and attacks on premises that sell alcohol.

They have further held several street protests calling for the enforcement of Sharia and often chanted in support of Osama Bin Laden, the al-Qaeda leader killed in a US raid in Pakistan in 2011.

In February, Tunis was brought to a standstill by a general strike and mass protests over the assassination of political leader Chokri Belaid, a prominent secular opponent of the Islamist-led government.

Ms Ben Mhenni showed me a recent YouTube video of a leader in the hardline Ansar al-Sharia group - which supports the introduction of Islamic law - attacking her on Tunisian TV.

"His statements are misleading really and taken out context to frame me," said Ms Ben Mhenni, who teaches linguistics at Tunis University.

"He took a photo of my Facebook with me brandishing a toy guy and called me terrorist. It is very naive of him really."

Ansar al-Sharia has found support in poorer areas of Tunisia

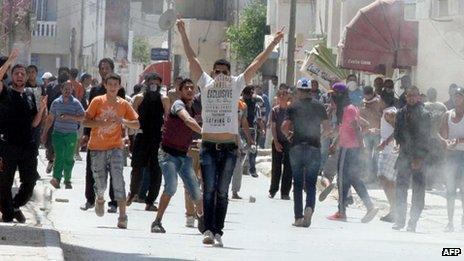

Members of the Salafi Ansar al-Sharia hit the headlines in May after violent clashes with security forces in protest at the government's banning of the group's annual conference.

The angry demonstrators and special forces turned a Tunis suburb into a battle zone, leaving one person dead and dozens injured.

The government is wary of the increasing influence of the group and accuses its leaders of inciting hatred and orchestrating violent incidents, allegedly including the attack on the US embassy last September.

An arrest warrant has been issued against the group's leader, Seif Allah Ibn Hussein, also known as Abu Ayadh al-Tunisi, who is still at large.

The group is very sceptical of both local and foreign media and have been reluctant to conduct any kind of interview since the confrontation with security forces.

But after two weeks of requests, they agreed to talk to the BBC.

Suspicious

"We are often misreported in the media and our statements misquoted," said Youssef Mazouz, a leader in Ansar al-Sharia's youth arm. He said the group did not support death threats.

I met Mr Mazouz, who is in his thirties and wears a long beard but is casually dressed, on the grounds of the ancient mosque in the coastal city of Sousa, a two-hour drive from Tunis.

The city is tourist-friendly but also one of the strongholds of the Salafi group.

Many times we were stopped filming by Salafists, who asked us to leave the area after a short argument about the role of media in "stirring up national discord".

"I apologise for their behaviour but they are very suspicious of the media, understandably," said Mr Mazouz.

He continued: "We agreed to this interview to get our message round the world that we are not a terrorist organisation as portrayed by the government and the West.

"We are a peaceful movement preaching for Islam," he said.

"Yes we want to apply Sharia and this is our opinion.

"We are just preaching and do massive charity in poor areas.

"We have made quite an impact there. You can go and check yourself in the regions neglected by the government."

I went to Ettadamun slum in southern Tunis where Ansar al-Sharia is quite popular and where there is evidence of deprivation and a lack of social services.

Bags of rubbish litter many unpaved streets and the smell of food waste is constantly in the air.

It is clear that people here struggle to make ends meet.

For needy families in the shanty towns of Tunis, the food, medicine and clothing handed out by Ansar al-Sharia - or any other group - would no doubt be very welcome.

Tunisian political pundits point not to the group's way of life or thoughts but to government neglect and poverty as the root of the area's festering problems.

"It has become a habit that parties and movements try to establish a strong base especially in areas with staggering unemployment and poverty," said respected author and columnist Qais Saidi.

"And the public service work done by Ansar al-Sharia can be easily translated into votes during elections."

The government says it inherited a heavy legacy from the former regime and needs time to sort out massive social and economic problems.

"We are working according to a five-year plan to fight poverty in the slums and have already mapped the most affected areas across the country," Mohammed al-Zaribi, under secretary at the Ministry of Social Affairs, told the BBC.

"There are up to 100,000 families who are living below the poverty line and our campaign is aimed at providing them with official cards to get subsidised and even free basic supplies," he said.

Many Tunisians are indeed concerned about scenes that were unimaginable in the past like women wearing niqabs or face veils and men wearing long beards in public.

But from her family home overlooking the Mediterranean on the outskirts of Tunis, Ms Ben Mhenni insists secularists "don't have a problem with religious people".

"We live in a democracy and everyone has the right to freedom of religion," she said.

"But we are campaigning against violent Islamists, who want to impose their evil ideology on society."