Nelson Mandela: Is it time for South Africa to let him go?

- Published

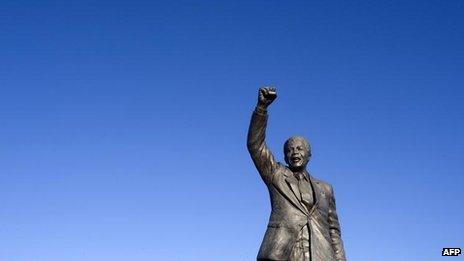

Many people still see Nelson Mandela as the antidote to current social ills

So deep is the affection in South Africa for the country's first black President, Nelson Mandela, that the thought of his passing seems incomprehensible.

But deep down the millions who adore him know that that day is inevitable.

Following a string of health scares in the recent past, South Africans are beginning to come to terms with the mortality of their 94-year-old icon.

Still, this in an uncomfortable topic here.

Somadoda Fikeni, head of the South African Heritage Resources Agency (Sahra), puts it this way: "We no longer have an icon on his level, not only here in South Africa but in the world.

"People see him as the antidote to the current social ills we are faced with. That is why people are still holding on to him."

Impossible love

South Africans see Mr Mandela as the glue that is holding the country together and believe that the social challenges of crime, poverty, corruption and unemployment can only be overcome if they have him to inspire the country's leaders to greatness.

It might be too high an aspiration to place on one individual, but in the eyes of many here, Mr Mandela is no mere individual.

Nevertheless, for the first time it seems that the tone surrounding Mr Mandela's increasingly frail health is beginning to change.

The Sunday Times newspaper at the weekend led with the headline: "It's time to let him go."

A blunt phrase bound to cause discomfort for the family and indeed many others in South Africa.

The usual response to Nelson Mandela's illnesses is a call to prayer

But these were not the words of someone who is nonchalant about what Mr Mandela represents to this country. These were the words of a dear friend and fellow Robben Island prisoner, Andrew Mlangeni, upon hearing that Mr Mandela had again been admitted to hospital.

"The family must release him so that God may have his own way with him... once the family releases him, the people of South Africa will follow," Mr Mlangeni was quoted as saying.

Many are fully aware of Mr Mandela's poor health and advanced age, but almost in the same breath they say they want him to live for many more years.

It's an extraordinary relationship, an impossible love.

At dinner tables South Africans talk about the Nobel Laureate's need to rest but none utter the phrase that could change it all: "Siyakukhulula tata" - Xhosa for "We release you, father".

According to Isintu - traditional South African culture - the very sick do not die unless the family "releases" them spiritually - only then will they be at peace in surrendering to death.

Culturally, this practice is seen as "permission" to die and this permission needs to be given by the family; it is reassurance from loved ones that they will be fine.

Mr Fikeni says that the other reason a person fights death is because they have unfinished business.

"It may be that squabbling within his family is troubling him and that needs to be addressed while he is still here. He may not be well received on the other side until these issues have been resolved."

This may be a reference to a recent court case which has seen an attempt by Mr Mandela's daughters, Makaziwe and Zenani, to oust three of his aides from companies linked to him.

Unenviable task

It is not easy to get people to speak about Mr Mandela's passing.

The BBC contacted three other cultural experts who refused to comment for fear of a backlash from the family or indeed fellow South Africans.

The press has been less fearful. Local and international media have reported on his four hospital visits since late last year. They camp outside hospitals for days eager to get an update on his health.

During the periods of his illness, the common theme in headlines is to call on South Africans to pray for his speedy recovery - further testimony that many are not ready to lose him.

But Mr Mandela's visits to hospital have become lengthier and his care more specialised.

President Jacob Zuma and a number of top officials from the governing African National Congress visited him at his Houghton home in Johannesburg shortly after his last release in April. Mr Mandela was seen sitting on a beige couch with a blanket on his legs.

He had a blank expression on his face. On his cheeks, the marks of where a hospital oxygen mask had been. The images were widely criticised.

This time around all we know is that he is in intensive care, and he is being treated for a recurring lung infection.

The presidency is juggling the need to inform South Africans and the world, while respecting the family's request for privacy. It is an unenviable task.

Anyone who has loved a father or grandfather can attest to wanting that person to live forever - people here see Mr Mandela as the greatest father there ever was.

He after all averted civil war, many South Africans believe, when he called on black and white people to reconcile amid marked racial tension, a time when South Africa seemed on the brink of collapse, destined to descend into anarchy like so many fellow African countries.

But the country still faces division; racism rears its head every so often, the ANC is more divided now than it has ever been.

A culture of tribalism is slowly creeping into the fibre of the new South Africa - some experts say this is due to a lack of firm leadership from the liberation movement.

These divisions are forcing South Africans to take a closer look at Nelson Mandela's dream of the "rainbow nation" and ask whether it is still alive - and whether it will live on after him.

Some still believe South Africa can surmount its challenges.

"It's a shared idea that what we have now is better than what he had in the past. All we need to do is hold on to this shared vision of a better South Africa," says political analyst, Ralph Mathekga.

Fears that Mr Mandela's passing will lead to anarchy are "unrealistic", he says, adding that South Africans need to focus on how they can continue the legacy.

"The best way to honour him will be to carry on his values of tolerance and conversation," says Mr Mathekga.

- Published8 June 2013