Mandela death: How he survived 27 years in prison

- Published

The BBC's Mike Wooldridge watches as Nelson Mandela is released from prison

"I went for a long holiday for 27 years," Nelson Mandela once said of his years in prison.

It was another example of the dry, razor-sharp and often self-deprecating humour for which South Africa's first black president was famous.

The prison years ended in a cottage he had to himself in the garden of a jail near Cape Town then known as Victor Verster - with TV, radio, newspapers, a swimming pool and any visitors he wanted.

But he was still in prison. And the greatest number of years that he was in prison - 18 out of 27 - were spent on Robben Island, where the contrast could not have been greater.

Banishment

The notorious island, within sight of the city of Cape Town and Table Mountain, acquired its name from the seals that once populated it in multitudes - robben being the Dutch word for seal. Its three centuries as a prison island and a place of banishment were punctuated by a period as a leper colony.

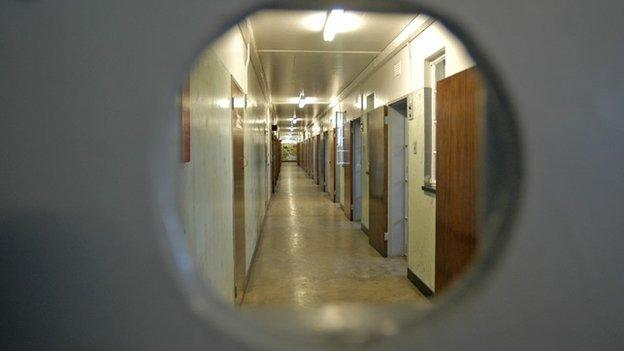

The longest spell of his prison life was spent on Robben Island

A warder's first words when Nelson Mandela and his ANC comrades arrived were: "This is the Island. This is where you will die."

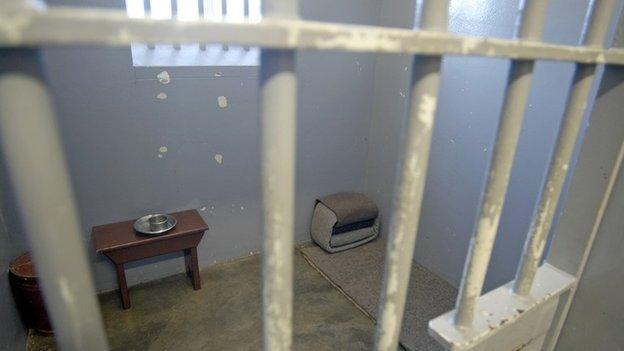

They faced a harsh regime in a new cell block constructed for political prisoners. Each had a single cell some seven foot square around a concrete courtyard, with a slop bucket. To start with, they were allowed no reading materials.

They crushed stones with a hammer to make gravel and were made to work in a blindingly bright quarry digging out the limestone.

Fellow prisoner Walter Sisulu spoke of a day Nelson Mandela's emerging leadership among the inmates was displayed in a rebellion over the quarry: "The prison authorities would rush us…'Hardloop!' That means run. One day they did it with us. It was Nelson who said: 'Comrades let's be slower than ever.' It was clear therefore that the steps we were taking would make it impossible ever to reach the quarry where we were going to. They were compelled to negotiate with Nelson. That brought about the recognition of his leadership."

Conditions on the island were difficult

Prisoner 46664, as he was known - the 466th prisoner to arrive in 1964 - would be the first to protest over ill-treatment and he would often be locked up in solitary as punishment.

"In those early years, isolation became a habit. We were routinely charged for the smallest infractions and sentenced to isolation," he wrote in his autobiography, The Long Walk to Freedom. "The authorities believed that isolation was the cure for our defiance and rebelliousness."

"I found solitary confinement the most forbidding aspect of prison life. There was no end and no beginning; there is only one's own mind, which can begin to play tricks."

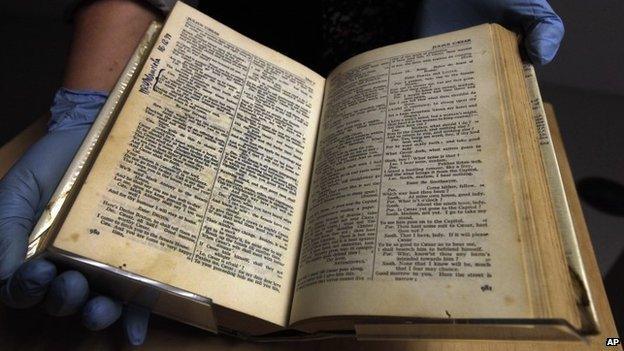

Access to books was sometimes limited - this complete works of Shakespeare was shared by Mandela, who signed this passage from Julius Caesar, as well as other inmates

Still, his determination and wit were clearly undiminished. His lawyer George Bizos saw it at first hand.

"On my first visit to Robben Island he was brought to the consulting room by no less than eight warders, two in front, two on each side and two at the back… in shorts and without socks. And the thing that was odd about it is that, unlike any other prisoner I have ever seen, he was setting the pace at which this group was coming towards the consulting room. And then with all gravitas he said 'You know, George, this place really has made me forget my manners. I haven't introduced you to my guard of honour'."

University behind bars

After the first few months on the island, life settled into a pattern.

"Prison life is about routine: each day like the one before; each week like the one before it, so that the months and years blend into each other," Mr Mandela wrote.

A portrait of Mandela now hangs in what was Victor Verster prison...

... and his statue stands outside the gates

Over time, and varying according to who was running the prison, so-called privileges would be granted. Those who wanted could apply for permission to study.

Although some subjects such as politics and military history were forbidden, Robben Island became known as a "university behind bars".

ANC and Communist Party stalwart Mac Maharaj remembers it as a cause of a falling out with Nelson Mandela.

"He was urging let us study Afrikaans and I was saying no way - this is the language of the damn oppressor. He persuaded me by saying,' Mac, we are in for a protracted war. You can't dream of ambushing the enemy if you can't understand the general commanding the forces. You have to read their literature and poetry, you have to understand their culture so that you get into the mind of the general.'

"Here he was showing right at the outset this focus of thinking of the other side, understanding them, anticipating them and so at the end of the day understanding how to accommodate them."

When Nelson Mandela reflected on his Robben Island experiences on returning there in 1994 he said: "Wounds that can't be seen are more painful than those that can be seen and cured by a doctor. One of the saddest moments of my life in prison was the death of my mother. The next shattering experience was the death of my eldest son in a car accident." He was refused permission to attend either funeral.

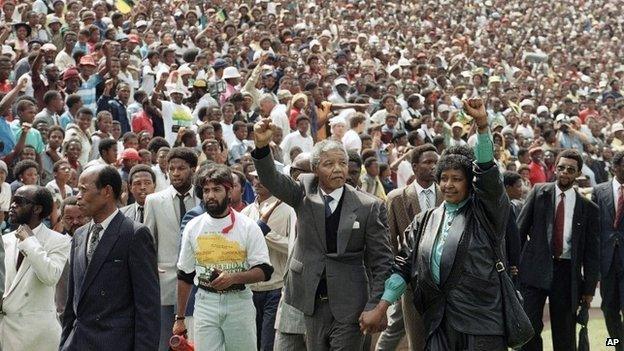

Mandela was said to be overwhelmed by the crowds who welcomed his release

Nelson Mandela's letters from prison to his second wife Winnie are poignant in the way they show the price paid for his total immersion in the anti-apartheid struggle, as is her account of this period.

Left to raise their children alone, Winnie once described the impact of taking them to see him in prison: "Taking them at that age to their father - their father of that stature - was so traumatic. It was one of the most painful moments actually. And I could see the strain on my children both before their visit and for quite some time after they had some contact with their father."

War of attrition

By the time Nelson Mandela was moved to Pollsmoor prison on the mainland, he was the world's most famous but perhaps least recognisable political prisoner. No contemporary photograph of him had been seen for years.

The late anti-apartheid activist Amina Cachalia, who had known him well before he went into prison, visited him. She told me she had taken a small camera into the prison with her, and as they had lunch she reached for her bag and said she was going to take a picture of him.

He held her by the arm and shook his head. She said Nelson Mandela was afraid they would confiscate the camera and terminate the visit.

Amina Cachalia laughed at the thought of the impact her photograph would have had. "He deprived me of being a millionairess," she joked.

Robben Island is now a tourist destination

Fellow prisoner Ahmed Kathrada recalled that in Pollsmoor in 1985, Nelson Mandela was called to the prison office and then returned to his ANC colleagues and started reading the newspapers. After a few minutes he said to them: "Oh by the way chaps, I was told President Botha has offered to release us."

"After 20 years or more of us being in prison and that's how cool he was… 'By the way this has happened'," Mr Kathrada told me. "We didn't even have to mull over it and that very night he wrote the letter. We all read through it and signed it, rejecting the offer."

Even though later Nelson Mandela was to have many meetings with the government and to be moved to the more comfortable conditions of his villa at Victor Verster prison - attending Sunday services, playing chess, teaching political economy to his fellow prisoners - he always sought to give the ANC exiled leadership no cause to be suspicious of his intentions and refused to put his own freedom before that of others and before the goals of the movement.

Ahmed Kathrada told me that Nelson Mandela fought a war of attrition in everything. In prison, he once played chess against a medical student who had just come in for five years.

"They played for many hours in one day and they had to ask the warders to lock the chessboard up in the cell next door. They continued the next day and each move was so slow this was a war of attrition. After a few hours the young chap said 'Look, you win. Just take your victory.' He wins."