Kenya violence: Survivors' tales

- Published

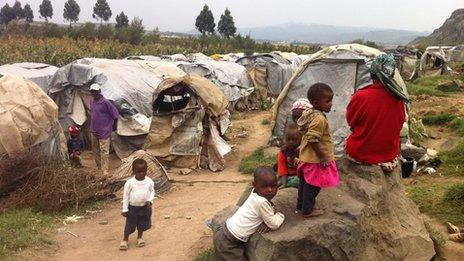

Many Kenyans have been living in camps since the violence which followed elections in 2007

For some, the Great Rift Valley is an exotic holiday destination.

But for the 500 residents of the Kihoto camp, what started as a temporary refuge has become a bleakly permanent residence.

"On the 27th of December, 2007, I cast my vote," says Geoffrey Mwaura, who remembers well the circumstances that brought him from his home in western Kenya to this wind-swept collection of tents, with their stick frames and dirt floors.

"On the 30th, that is when it erupted. Every house was torched.

"The Kalenjin started torching our houses and beating us."

In Kenya's ethnically divided politics, the 2007 election pitted the Kikuyu ethnic group, whose leader Mwai Kibaki was declared the winner, against Kalenjins and Luos, who believed their man, Raila Odinga, had been cheated out of victory.

"It was like a killing spree: killing, maiming, torching houses. Then everybody had to run for his dear life," Mr Mwaura says.

"That's what I did myself. I ran for my life."

Mr Mwaura remembers having to negotiate a road-block made out of dead bodies, lined up across the road.

"Jumping corpses, jumping dead bodies. I did it. I myself."

The violence was particularly acute in the west of the country, and in the Rift Valley, where different communities lived alongside one another.

Search for justice

An estimated 1,200 people were killed. Around 600,000 fled their homes.

Kenya has failed to hold the perpetrators to account.

And so, many of those seeking justice are looking to The Hague.

"Kenyans have lived with impunity for half a century now," says Njonjo Mue, the head of the International Centre for Transitional Justice (ICTJ) in Nairobi.

"Many Kenyans recognize that the possibility of bringing high-level politicians to account is almost nil using the local courts."

President Uhuru Kenyatta, a Kikuyu, and his deputy William Ruto, a Kalenjin, formed a coalition to fight the 2013 election together.

But in 2007 and 2008, they were on opposite sides of the divide.

They will stand trial at The Hague on charges of crimes against humanity: They are accused of inciting their supporters to kill one another, charges they both deny.

But the cases against them are looking shaky. Witnesses have been disappearing, or withdrawing their testimony. The prosecution says some have been threatened, others bribed.

Threats

Ken Wafula showed us an anonymous email he received at the end of May:

"Why are you bringing rumours to The Hague?" it reads in Swahili. The message then continues in English:

"Ruto is our leader and future president. Your days are numbered. You will soon be kaput."

Mr Wafula says he doesn't know who sent that message, but he believes he has been targeted because of his work with some of the victims and witnesses to the violence.

"The last five years I have never had peace," he says.

"I've been arrested on trumped-up charges and it has been hell, especially the last two months."

Last week, the Kenyan parliament voted to withdraw the country from the International Criminal Court, which is behind the Hague trials. Some MPs described the court as part of a neo-imperialist plot that violated Kenya's sovereignty.

The move won't affect cases already active, but the issue is becoming increasingly politicised.

Propaganda

People stuck in Kihoto camp for displaced persons say their lives are on hold

"In recent times, especially in the lead-up to the March 4th [2013] election, there has been a lot of rhetoric and propaganda that has seemed to drown out the desire for justice for post-election violence," says Mr Mue.

"The candidates who ended up being elected president and deputy president [Uhuru Kenyatta and William Ruto] managed to conflate their personal fortunes at the ICC with the national interest and make it a campaign issue.

"And therefore people started buying the idea that the ICC was an imperialist court with a political agenda and not just a judicial process, which is what it is."

But the politics and the intrigue surrounding the cases at The Hague feel very remote at the Kihoto camp in the Rift Valley.

Five years after the people here were chased from their homes, they are still waiting to be resettled by the government, and their lives are on hold.

"We are not ready even to have children again, because we don't know if it will happen again," says Rosemary Wangari, who gave birth to her son Isaac as she fled her home at the height of the violence five years ago.

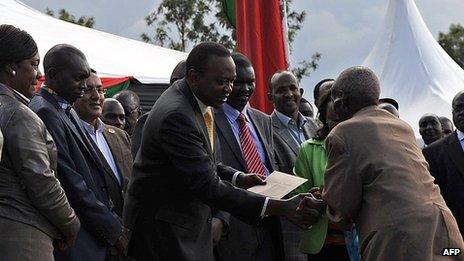

Cheques

On Saturday, Mr Kenyatta and Mr Ruto handed out cheques worth more than $4,500 (£3,000) to families living in a different camp in the Rift Valley.

The government says it is part of a programme that will see all IDP (Internally Displaced Persons) camps closed by 20 September.

But according to Kefa Magenyi, of the National IDPs Network, there are still 46 camps dotted around the country, with as many as 200,000 residents. Many have not been recognized under the scheme.

Kenya's President Uhuru Kenyatta and his deputy, William Ruto, distributed money to displaced persons at a camp in Eldoret on 7 September

Kihoto is one such camp. Geoffrey Mwaura accuses the government of airbrushing him and his fellow residents out of the records.

"Is this not a camp?" he asks, pointing to the tarpaulin tents.

I asked him whether, with the new political alliance between Mr Kenyatta and Mr Ruto in place, it might be safe enough to return home. Mr Mwaura dismissed the idea:

"The person who took the arrow, the person who took the panga [machete], is still on the ground. I'll find him there.

"Now telling me to go back there, [it's] as if you are telling me to commit suicide. And I'm not ready to do that.

"Better the government kill me than I go back there."

For Geoffrey, Rosemary and thousands of others, the trials at the ICC are a side-show. For them, justice will not be served until they have somewhere they can call home.

The Kihoto camp in the Rift Valley is not part of the Kenyan government's scheme to close displaced persons' camps

- Published13 September 2022

- Published8 February 2013

- Published27 May 2013

- Published7 January 2015

- Published12 December 2011