Tunisia crisis: Fears grow over political paralysis

- Published

Tunisia's politicians, including Prime Minister Ali Larayedh (top, centre), are a focus for public anger

Hope is in rare supply in Tunis. More than two months after the second assassination of a prominent politician from the opposition, politics is paralysed and the economy is drifting deeper into trouble.

Not since the overthrow of former strongman Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali in January 2011 has the country experienced a political crisis so complicated.

"You can trace the disappointment of the average people from the anti-government protests that go on almost non-stop here in the capital," said Khansaa Chabaan, a 21-year-old university graduate.

Ms Chabaan was at a rally on 2 October outside the headquarters of the government at al-Qasba Square in central Tunis.

She is a member of the country's leading youth opposition movement, Tamrood, Arabic for "rebellion", which organised the latest rally.

The July assassination of Mohammed Brahmi touched a nerve.

It brought supporters of the secular opposition on to the streets to demand the downfall of the government which they accuse of procrastination and having a deliberately lax attitude toward acts of organised political violence blamed on Muslim extremists.

"Radical Islamists are left unchecked by Ennahda," said Ms Chabaan, referring to the country's largest Islamist movement, which led a coalition government with two secular parties after emerging triumphant in the parliamentary elections of October 2011.

The country's powerful labour union, or UGTT, is championing an initiative with the aim to end the political crisis.

The initiative, which has been accepted by the three-party ruling coalition, basically calls for the resignation of the government, the appointment of an independent politician to form a new non-partisan interim cabinet and holding parliamentary and presidential elections as early as possible.

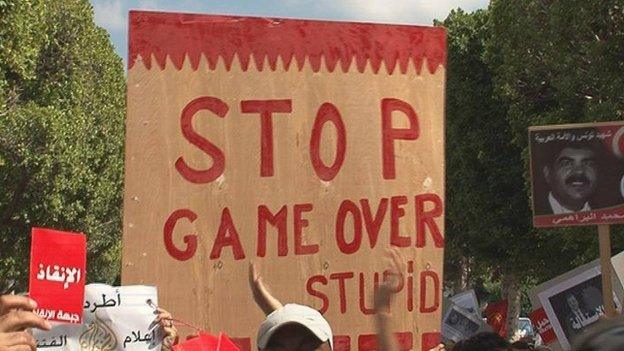

Anger has been building in the streets of the capital about the country's political situation

Food prices have jumped and investment is moribund, stoking further tensions

Some fear the frustration may result in a popular overthrow of the government

Ennahda leaders, however, ruled out the immediate resignation of the government to head off a political vacuum, saying it would step down only if a proposed national dialogue with political rivals succeeded in reaching a consensus on a new prime minister.

The frustration can be sensed in conversations with people from all backgrounds; from young activists and journalists to cab drivers and hotel receptionists.

People are fed up with politics and do not care about the talk of rising Islamism or of the al-Qaeda-affiliated terrorists the army has been fighting in the Chaambi mountains (west of Tunis) since December 2012.

They only care about skyrocketing food prices and the moribund economy.

Promises

Economic problems were one of the main driving factors behind the 2011 revolution.

The governor of the country's Central Bank, Chadi Ayari, said this week the failure of politicians to resolve the political crisis threatens the country's economy.

"Every time I meet foreigners looking to invest in Tunisia, they begin asking questions about the political situation. Their problem is not so much economic as political," he told reporters on the sidelines of a meeting of Arab central bankers in Abu Dhabi, in the United Arab Emirates.

The first democratically-elected government in Tunisia's modern history says it has inherited a heavy burden from the ousted regime and needs time to make good on its promises of economic prosperity.

Critics say it is easier said than done.

The unspoken fear in the streets of the capital is that the country is heading towards an Egyptian scenario that saw the overthrow of an Islamist president and his government by a combination of popular rejection and military muscle. People fear the consequences.

Many Tunisians are therefore pinning high hopes on national dialogue, and perhaps the country's window of hope has not yet shut.