'Easier from Libya' - Migrants return to Tripoli

- Published

This man's tattoo says "Leave: I must"

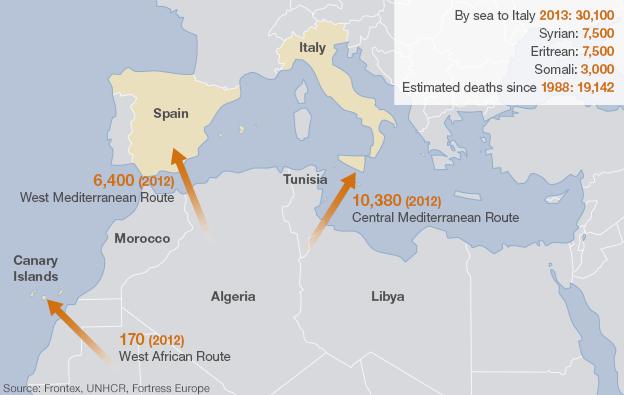

Migrants and people traffickers have long seen Libya as the best way of getting from North Africa to Europe.

Its extensive land and sea borders are perfect for smugglers, as is its proximity to European shores.

During the conflict which saw long-time leader Muammar Gaddafi toppled in 2011, migrants went elsewhere but now they have returned.

While the country is mostly peaceful, the state has been unable to impose control, meaning the security forces are often unable to pursue the trafficking gangs.

Two Tunisian migrants in Tripoli summed it up by saying it's "easier from Libya" - even though their home country is also a major hub for those trying to reach Europe.

Both men, in their 20s, have friends or family who have made the journey across the sea from Libya and have settled there, married foreign nationals and encouraged them to follow suit.

As one of them put it emphatically: "If I die on the way, then I die. I would rather die than live in poverty."

'Never get married'

Both are disenchanted by the realities they faced at home and determined to make the journey at any cost.

One of them says half the men in his neighbourhood in Tunisia have done whatever they could - sold their mother's gold, the goat or cow on the farm - to get the money needed for a boat, often from Libya.

He has tried to reach Europe from Tunisia four times without success and says he is going to try from Libya as soon as he has enough money.

These migrants were saved by a Maltese patrol boat after their boat sank

We are told the journey could cost up to $2,500 (£1,500). But they stop short of giving any further details on the smuggling ring that facilitates the journey.

The younger of the two is 23 years old. He is so determined to leave for Europe that he has permanently inked it on his finger as a reminder: "Partir | JDS", meaning Leave: I must (JDS is short for "Je dois").

"I heard about it before the Libyan revolution - that migrating from Libya is good, that it's better than from Tunisia. If you wanted to migrate from Tunisia, you have a 50% chance of making it but from Libya it's like 90% or 80%."

He goes on to say: "Half of the [residents of the] street where I live here in Libya migrated and they are now married to French women and living in France and have invested in Tunisia and their lives are good.

"If you live another thousand years in Tunisia you won't achieve anything, you can't even get married and you'll live in poverty."

He says he has thought of nothing else but a way to get to Europe since he was 16.

Seeking work

It is impossible to get reliable figures for how many migrants pass through Libya.

But it is accepted that numbers plummeted after the war because at the time many sub-Saharan Africans were accused of being mercenaries who fought for Col Gaddafi.

Many sub-Saharan Africans left Libya after Col Gaddafi was toppled

People who had lived and worked here for many years - albeit illegally - fled to their home countries in case they were rounded up and detained.

They didn't feel safe after the war ended and they were less visible on the streets.

But now sub-Saharan Africans are once more sitting by Tripoli's roundabouts or beneath the bridges of popular areas, seeking work as plumbers or carpenters.

On Sunday, Libyan Prime Minister Ali Zeidan acknowledged that illegal migration was sometimes "out of the hands of the authorities", no matter how much they tightened border controls.

He was speaking at a joint news conference with Maltese Prime Minister Joseph Muscat, who had gone to Tripoli to discuss the issue.

Mr Zeidan said his government had asked the EU for a number of things, including: "training, equipment, and help in allowing us to access the European satellite system to help us better monitor our shores, our southern land borders and inside the country as well. If we manage this, it would be important for our surveillance".

In recent months, the EU has been assisting the Libyan authorities with an "integrated border management strategy".

But it is not clear how much of that has been implemented, or is producing results.

Full circle

Libya's inability to enforce its security was highlighted when the prime minister himself was briefly kidnapped last week by a militia loosely allied to the interior ministry.

The spokesman for Libya's land border patrol units, Ahmad Bashaer, has bemoaned their lack of capacity to deal with the scale of the problem.

Conditions in Libya's detention centres have been criticised

He told the BBC that they arrested many sub-Saharan African nationals, deporting illegal migrants crossing through the desert, "on a daily or weekly basis", or handing them over to detention centres.

These centres, many of which are overseen by militias linked to the government, have been condemned by human rights organisations for alleged mistreatment and torture.

They used to make similar complaints while Gaddafi was in charge.

While he was in charge, Libya had an agreement with Italy under which migrants were returned to Libya, where they were often kept in jail or immediately deported on planes to their homelands without any filter to divide genuine asylum-seekers from economic migrants.

This agreement was heavily criticised by human rights groups.

Libya still has no legislation governing asylum-seekers.

The issue of migration has long been seen as a problem of "border monitoring".

What is asked less frequently is what can be done in the countries of would-be migrants to give them a reason to stay or perhaps an opportunity to travel through legal, less potentially fatal channels.